Culture Changer

She was born on the Cherokee reservation in Oklahoma, but then the federal government relocated her family to California. While in San Francisco, she became an advocate for the rights of Native Americans. Eventually, she decided to move back to Oklahoma and use her advocacy skills to help her people and community. She dedicated the rest of her life to the Cherokee Nation. Step back to 1985 and meet Wilma Mankiller …

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

Wilma Mankiller stared at the paper in her hands. It was 1985 and she was officially appointed as Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation. She couldn’t believe it — she was the first woman to be chief of a major American Indian tribe. Wilma was a strong leader and dedicated her time to helping the Cherokee Nation, as well as advocating for all Native nations.

But not everyone was ready to accept her leadership. Some were opposed to a woman serving as Chief, while others argued that they never elected her to the position (she was appointed after Principal Chief Ross Swimmer resigned). So they tried to manage the tribal government without her and excluded her from Tribal Council meetings.

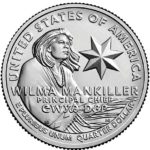

Wilma Mankiller (Cherokee Nation)

Early in her tenure, Wilma was not invited to attend a critical, large meeting of multiple American Indian tribes. When she found out about the meeting, however, Wilma sprang into action. She forced her way into the meeting, found a chair, and dragged it to the table. After the meeting was over, she stood up and gave the entire room a piece of her mind. After that, she was never excluded from a meeting again.

While Principal Chief, Wilma focused on community development projects — modernizing infrastructure such as electricity and water; increasing educational opportunities; improving health care; and lowering the unemployment rate. For example, she expanded the Head Start program for children on tribal lands. She also opened three rural health centers and a center for prevention of drug abuse. Further, she worked with the EPA to build a power plant on the reservation so that all tribal members could have electricity. She also created the Institute for Cherokee Literacy, with the goal of preserving and promoting Cherokee traditions.

Wilma also founded the Cherokee Nation’s chamber of commerce while she was Principal Chief. She encouraged tribally owned businesses and worked tirelessly to develop the economy of the region. By the time her tenure ended, Wilma oversaw a $150 million budget for the Cherokee Nation.

Wilma also founded the Cherokee Nation’s chamber of commerce while she was Principal Chief. She encouraged tribally owned businesses and worked tirelessly to develop the economy of the region. By the time her tenure ended, Wilma oversaw a $150 million budget for the Cherokee Nation.

In addition, Wilma updated the governance structure of the Cherokee Nation. She improved the tribe’s relationship with the federal government. She also focused on increasing women’s participation in tribal affairs and leadership. She also negotiated a self-governance agreement with the federal government, which ultimately led to tribal sovereignty. And she revised and updated the Nation’s legal codes and laws.

Members of the Cherokee nation liked her leadership. In fact, the Cherokee Nation population more than doubled while she was Chief, from 68,000 to 170,000 people. Wilma ran for re-election in 1987 and 1991 and won both times. She chose not to run for another term, and resigned as Principal Chief on April 4, 1994.

The Power of the Wand

Wilma Mankiller devoted her life to advocating for the rights of American Indians. As the first woman Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation, she worked tirelessly to modernized the tribe while preserving its culture. After her time as Principal Chief, she went on to help establish the Office of Tribal Justice within the US Department of Justice. She was also a founding member of the organization, Women Empowering Women for Indian Nations. Her efforts have empowered indigenous women throughout America ever since.

Her Yellow Brick Road

After Wilma moved back to Oklahoma in 1977, she used the advocacy skills she learned in San Francisco to help the members of her community. She knew about all the challenges they face, and wanted to give them the tools to help themselves.

Wilma Mankiller on 2022 US Quarter (US Mint)

Wilma was also was determined to graduate from college. So she took classes in community planning at the University of Arkansas and earned her degree. Then, she got a job as economic stimulus coordinator for the Cherokee Nation.

Wilma went on to help establish the Community Development Department for the Cherokee Nation. Its goal was to improve access to water and housing on Cherokee lands. The first project was in Bell, Oklahoma, a small Cherokee community of about 200 people. Called the Bell Community Revitalization Project, its goal was to provide homes, jobs, and running water to the community. Wilma was responsible for raising the funds necessary for the Project. Over the course of 14 months, the community worked together to build a 16-mile water pipeline to bring water to their town. The Project received nationwide attention and became a model for other tribes. Their success was documented in a film called “The Cherokee Word for Water.”

The Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation, Ross Swimmer, noticed her accomplishment and asked her to be his running mate for his third term. In August of 1983, she was elected Deputy Principal Chief. It was a rough campaign for Wilma, however. Many people within the tribe weren’t ready for a woman leader — she experienced harassment and received death threats on a regular basis. But she refused to quit.

The Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation, Ross Swimmer, noticed her accomplishment and asked her to be his running mate for his third term. In August of 1983, she was elected Deputy Principal Chief. It was a rough campaign for Wilma, however. Many people within the tribe weren’t ready for a woman leader — she experienced harassment and received death threats on a regular basis. But she refused to quit.

About 18 months later, Ross Swimmer was appointed as the Assistant Secretary of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Since she was second in line, she became Principal Chief when he resigned from the position. She was suddenly the leader of one of the largest Native nations in America.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Wilma grew up on a farm in Mankiller Flats, Oklahoma with 10 siblings. It was the farmland allocated to her father as a member of the Cherokee Nation, under the government settlement after the forced relocation of his tribe. Her family’s home was a wooden shack without running water, sewer, or electricity. Life was hard, but they had their community. Then, a drought in 1956 made it impossible to stay on their farm.

Wilma as a student (Washington University)

The Mankiller family moved to San Francisco, as part of the Indian Relocation Act when Wilma was 11 years old. The US Bureau of Indian Affairs encouraged Native Americans to move from their rural homes to urban areas. It was a tough adjustment for Wilma, since they were the only Native Americans in their neighborhood. Wilma had never used a phone — never mind the traffic, bright lights and tall buildings. And she was teased at school for her name and heritage.

Wilma graduated from high school, got married, had kids, and was a homemaker. But she was restless and unhappy. Then, in 1969 a group of young people took over Alcatraz Island and claimed it “in the name of Indians of all tribes.” They protested the poor treatment of Native Americans across the country by the federal government. The protestors called themselves the American Indian Movement (AIM) and had the goal of reclaiming the land of Alcatraz Island for Native people. Wilma saw coverage of the protest on television and was intrigued. She visited the island many times over the 18th-month protest and raised money to support the protestors. It changed her life.

Wilma attended college at San Francisco State University, so that she could learn how to become a better advocate. She studied sociology, social work and community planning. She put her new skills to use as a social worker, eventually becoming director of Native American Youth Center in Oakland. She also became involved in the legal battle between the Pit River Tribe against Pacific Gas and Power regarding the rights over millions of acres of tribal property.

As Wilma became more involved in advocacy work, she became inspired to reconnect with her heritage and help her own community. So she decided to move back to Oklahoma.

Want to Know More?

The Cherokee Nation website (https://www.cherokee.org)

Mankiller, Wilma. Mankiller: A Chief and Her People. (New York: St. Martins Griffin, 1999).

Wilma Mankiller Foundation (http://mankiller.org)

Wilma Mankiller, National Women’s History Foundation (https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/wilma-mankiller)

Wilma Pearl Mankiller, the Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture (https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=MA013)

Women Empowering Women for Indigenous Nations (https://www.wewin04.org/about-wewin)