Amazing Artist

She was a rebel and mother of four whose fascination with the relationship between witchcraft, ghosts, and the workings of the human mind inspired her to write some of the most thoughtful (and scariest) gothic horror stories of all time. One of them was a finalist for the National Book Award and is still terrifying audiences more than 40 years later. Step into The Haunting of Hill House in 1959 and meet Shirley Jackson…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

Shirley Jackson looked around her remodeled home in North Bennington, Vermont, with immense satisfaction. After nearly 20 years, her family finally was financially stable enough to pay off the mortgage and update the house. And Shirley was the one who made it possible, with the profits from her wildly successful new novel, The Haunting of Hill House. It had been published on October 16, 1959 to great acclaim. The Wall Street Journal called it “the greatest haunted house story ever written.” A New York Times reviewer said it was “the most spine-chilling ghost story I have read since I was a child.” It was a finalist for 1960 National Book Award.

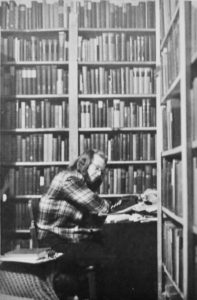

Shirley at work in her study at home. (Library of Congress)

Since childhood, Shirley had been interested in witchcraft, ghosts, tarot cards, and magic. The author’s notes in her first novel described her as “perhaps the only contemporary writer who is a practicing amateur witch.” She was open to the possibility of poltergeists. She kept a menagerie of black cats, telling her husband they only had a few, which he believed because he couldn’t tell them apart. Shirley believed that houses were, in a sense, alive, channeling the energy of those who lived in them.

Shirley got the idea for The Haunting of Hill House while she was looking out a train window on the way to New York City. She noticed a decrepit apartment building and immediately felt chills from its haunted aura. Upon arrival, she investigated and discovered the apartment had been the scene of a fire where many people died. She asked her companions in the city if they believed in ghosts, and was intrigued when most answered that while they had never seen one themselves, they believed it was possible.

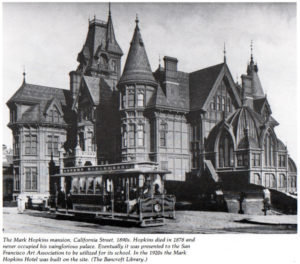

As soon as she returned home, Shirley started work on a haunted house novel. She asked her mom to send pictures of old San Francisco mansions and received photos of two homes that had been designed by Shirley’s architect great-great-grandfather. Both had tales of misfortune connected to them. Shirley used them as inspiration for Hill House, which she filled with gables and turrets, hallways that lead nowhere, lots of doors, and windowless rooms.

Shirley also did research on the supernatural. She read newspaper articles and books about ghostly encounters. In one, An Adventure, two women claimed to have encountered a group of ghosts at Versailles. Another detailed a report from a group of 19th century psychic researchers who studied a haunted house.

Shirley also did research on the supernatural. She read newspaper articles and books about ghostly encounters. In one, An Adventure, two women claimed to have encountered a group of ghosts at Versailles. Another detailed a report from a group of 19th century psychic researchers who studied a haunted house.

Shirley began writing in Fall 1958. The story didn’t come easily, and she regularly threw half of it away. She didn’t finish until the following spring. She wrote at home, often talking, crying, or laughing out loud. Her husband, usually one of her most active editors, wouldn’t read it because he was afraid of ghosts.

The center of the novel is a woman named Eleanor, who has had paranormal experiences. After her dad died when she was 12, stones fell on her house for 3 days. As an adult, she agrees to assist an investigation to determine whether Hill House, with its legacy of mysterious deaths, is haunted. She lives in the house for a summer with three other people.

They start to hear banging on doors and knocking on walls. Something or someone writes messages on the walls, in chalk and blood. One such message is “help Eleanor come home.” They see ghosts. One night, Eleanor hears a child crying, grabs her roommate’s hand in the dark, and screams. When the light turns on, her roommate is across the room, leaving her to wonder “Whose hand was I holding?”

One of the San Francisco mansions that inspired Hill House (Bancroft Library)

Eleanor is the most affected by whatever is in the house, and it is left unsaid whether the ghosts belong to Hill House or if Eleanor brought them with her. The more untethered from reality she gets, the more convinced paranoid she gets. She wants to go home but doesn’t know if she can escape whatever is haunting her.

Shirley was inspired by her own experience that surroundings affected mental state. She suffered from panic attacks, largely triggered by conflict between her fears of being alone and of staying in her complicated marriage. Shirley often felt like two different people: one powerful and a bit angry and the other scared and anxious. Many of her characters, like Eleanor, also felt trapped and misunderstood by the people around them. Readers are left with the question, was Hill House haunted, or was Eleanor?

The Power of the Wand

Shirley’s stories continue to capture imaginations to this day. The Haunting of Hill House was adapted into movies titled The Haunting in 1963 and 1999. Netflix aired the series The Haunting of Hill House in 2018, and its sequel, The Haunting of Bly Manor in October 2020.

Shirley started writing when she was young. Today, there are many resources for tweens and teens who want to be writers, like Teen Ink and Get Underlined. Both include advice for aspiring authors and a place to submit stories and poetry for others in the community to read.

Her Yellow Brick Road

Shirley lived in Vermont for most of her professional life, moving there when her husband became a professor at Bennington College. She had multiple roles: faculty wife, mother of four children, and writer. Shirley made a point of being a different mom than her own mother was, prioritizing a warm, imaginative environment where she celebrated her kids for who they were.

Shirley with her four children (Erich Hartmann/Magnum)

Although Shirley wrote funny articles about her family for women’s magazines, she was often frustrated by the constraints she felt as an unconventional woman with strong opinions and passions. The locals treated her with caution. One day, Shirley saw kids throwing stones in the village center. Inspired, she went home and, in just a few hours, wrote a short story she called “The Lottery.” It begins with a village of seemingly normal people gathered in the village square for a lottery. It is slowly revealed that they are participating in an annual stoning ritual where the victim is chosen at random.

“The Lottery” was published in the New Yorker in 1948 and was an instant phenomenon. The magazine received hundreds of letters from people disturbed by the story – more than they ever had before. Many were upset by the characters’ willingness to harm one another out of fear and superstition. Shirley was now famous, and her neighbors very insulted as they assumed (correctly) that the story was inspired by them.

“The Lottery” was so popular that Shirley included it in a collection of short stories published the following year titled The Lottery: or The Adventures of James Harris. It was marketed with an emphasis on its gothic horror and Shirley’s interest in witchcraft. Her first full novel, The Road Through The Wall (1948) also played up this angle. By 1950, “The Lottery” was everywhere, including school curriculums, television events, and onstage.

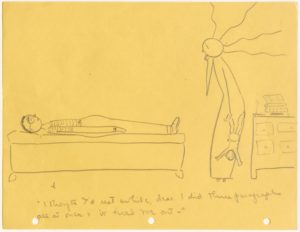

One of Shirley’s cartoons depicting a scene from her life.

With her new fame, Shirley started lecturing at Bennington and found she loved talking about writing. She presented at writer’s conferences and started earning more money than her husband. As Shirley gained more recognition, her marriage suffered. Her husband was a good editing partner but also resented her success. He controlled the money and often treated her with disrespect.

Shirley continued writing gothic horror and psychological suspense. Her second novel, Hangsaman (1951), was about a struggling college student with a new friend who may be a figment of her imagination. Her third novel, The Bird’s Nest (1954), told the story of a quiet woman who discovers she has multiple personalities, including one evil one. Both novels were critical hits but not profitable. Shirley began exploring the pull houses have on their residents in her fourth novel, The Sundial (1958). The novel is about an impending apocalypse, where the characters believe only the house and those inside will remain untouched.

Shirley’s book covers. (Ryan MacEachern/Penguin)

Shirley often felt like she was juggling two personalities, one who wrote gothic horror and the other lighthearted non-fiction about her family. Her first “mom” book was a collection of stories called Life Among the Savages (1953). Readers loved how Shirley wrote about motherhood in a new and modern way, with honesty and humor. The book was a best seller. She wrote a sequel titled Raising Demons (1957).

Not long before she started working on The Haunting of Hill House, Shirley wrote a non-fiction book for older children titled The Witchcraft of Salem Village. Shirley didn’t view witchcraft as evil, but instead saw it as an idea used to control women who are unwilling to conform to societal expectations. Salem accused its outsiders of being witches, and they had no way to prove their innocence. Every denial was evidence of witchcraft, and any defenders were labeled witches too. Citizens turned on each other so the eye of judgement wouldn’t turn on them. Shirley described this behavior as “the demon in the mind,” which creates “hatred and anger and fear” and “being someone else and doing the things someone else wants us to do.”

Brains, Heart & Courage

Shirley was the square peg in the round hole of her family. She spent most of her childhood in Burlingname, an affluent San Francisco suburb. Her parents were conservative and valued conformity. They had hoped for a quiet, obedient daughter. Instead, Shirley was imaginative, emotionally volatile, and stubborn. Throughout her life, her mom criticized her personality and appearance.

Shirley spent her free time writing or drawing. She hid most of her writing from her parents, although at times she shared something publicly. She was editor of her elementary school newspaper, wrote a graduation play for her fifth grade class, and won a Junior Home Magazine poetry contest when she was 12. Her grandfather was a third generation architect whose family had designed and built some of San Francisco’s most famous mansions. Shirley was fascinated by them and sketched many different homes for her stories. She also drew cartoons of family and friends.

Shirley spent her free time writing or drawing. She hid most of her writing from her parents, although at times she shared something publicly. She was editor of her elementary school newspaper, wrote a graduation play for her fifth grade class, and won a Junior Home Magazine poetry contest when she was 12. Her grandfather was a third generation architect whose family had designed and built some of San Francisco’s most famous mansions. Shirley was fascinated by them and sketched many different homes for her stories. She also drew cartoons of family and friends.

As a teenager, she kept multiple diaries. In one, she wrote as a typical American teen, detailing her daily life. In another, she wrote letters to a boy sharing her personal thoughts. She had another for exploring her moods, giving each one a name like it was a separate personality. She continued to write poetry and stories, later reflecting that “I used to think that no one had ever been so lonely as i was and i used to write about people all alone. . . .and how the whole world is cruel and foolish and afraid of people who are different.”

Shirley in 1938 (June Merkin Mintz)

Her family moved to New York the summer before her senior year. She was an average student, other than As in English. When she went to the University of Rochester, she was derailed by anxiety attacks and put on academic probation. She returned home after two years and devoted herself to writing at least 1000 words a day.

Shirley tried college again a year later at Syracuse University, keeping her bags packed for the first three days in case she changed her mind. She found a community of writers and became editor of a campus magazine. A fellow student read one of her stories and sought her out. Together they founded a college literary magazine, began dating, and moved to New York City after graduation to work for the New Yorker magazine.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- Shirley was born in San Francisco on December 14, 1916.

- Shirley married Stanley Edgar Hyman in 1940. Stanley was Jewish, Shirley was Christian, and both families disapproved. Shirley didn’t tell her parents they were married until she was pregnant with her first child two years later.

- When Shirley checked into the hospital to have her 3rd child, the clerk asked for her occupation and she said writer. The clerk instead wrote housewife.

- The Hymans’ personal library had 25,000-30,000 books. During one of their moves, a mover noticed some “suspicious” books and reported them to the FBI, who then investigated Stanley for Communist ties.

- After writing The Haunting of Hill House, Shirley began to suffer many health issues, including arthritis in her fingers, colitis, and anxiety attacks. She struggled with writer’s block.

- Shirley was nominated for two Edgar Allan Poe Awards (now called the “Edgars”), awarded by the Mystery Writers of America for the best in mystery literature. In 1961, she was nominated for the short story “Louisa, Please Come Home.” She won in 1966 for the short story “The Possibility of Evil.”

- Shirley published the novel We Have Always Lived in the Castle in 1962. It received rave reviews and was her first New York Times best seller. It is the story of two adult sisters, Merricat and Constance, who live together in their childhood home. Years before, everyone else in their family died from poisoning at dinner. “Time” magazine named it one of the year’s 10 Best Novels and did a feature on Shirley. Shirley’s mom sent her a letter criticizing Shirley’s “embarrassing” physical appearance in the magazine’s photo. This, plus a fall, triggered a nervous breakdown in late 1962. Shirley did not leave her house for 6 months and was unable to write for 2 years.

- Shirley kept a journal to help her writer’s block. She imagined a future where she let go of her fear, left her complicated marriage, and took control of her life. After Shirley recovered, she began teaching at the prestigious Middlebury Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference and started writing a comic novel and began a story about a widow who starts a new life in a boarding house.

- Shirley died in her sleep of heart failure August 8, 1965. She was 48.

- Stanley published two collections of Shirley’s work after she died: The Magic of Shirley Jackson in 1966 and Come Along With Me in 1968. Two of Shirley’s children collected her unpublished short stories into Just An Ordinary Day: Stories in 1997.

- The Shirley Jackson Awards were established in 2007 to honor outstanding achievement in literature of psychological suspense, horror and dark fantastic.

- Syracuse awarded Shirley the George Arents Award, its highest alumni honor, in 2008.

Want to Know More?

Franklin, Ruth. Shirley Jackson, A Rather Haunted Life (Liveright Publishing Corp. 2016).

Guran, Paula. “Shirley Jackson & The Haunting of Hill House” (Dark Echo Horror July 1999)

Heller, Zoe. “The Haunted Mind of Shirley Jackson” (New Yorker Oct. 17, 2016)