Culture Changer

She left her home in Puerto Rico when she was 20 and leveraged her bilingual Spanish/English skills into a job at the New York Public Library. From there she used her creativity, love of folktales, and magnificent puppets to inspire generations of children to learn to read. Pull up a piece of carpet in the children’s section of Harlem’s 115th Street Library, listen as she reads from her 1946 collection of Puerto Rican folktales – the first of its kind published in the United States – and meet Pura Belpré…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

Storyteller Pura Belpré looked at the children sitting around her and remembered how much she loved sitting at her grandmother’s feet, listening to her weave stories about clever and adventurous animals and their adventures. Her grandmother told Pura that these stories had been told in her family, and in their homeland of Puerto Rico, for generations. While each story typically had a lesson hidden within it, the characters were so interesting, and often silly, that the wisdom they shared was part of the fun.

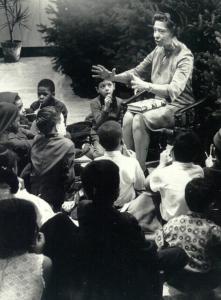

Pura telling stories at the NY Public Library (Centro Archives)

Pura had been in New York City for 25 years. She had immediately fallen in love with the city, with its fast pace and people from all over the world, but part of what kept her centered was her childhood connection to Puerto Rico. She hadn’t moved away from home until she was 20, much older than the Puerto Rican children she worked with as a librarian in Harlem. As the first Puerto Rican librarian in the New York Public Library system, Pura wanted those kids to experience the rich tradition of storytelling she had growing up, even though they wouldn’t be in Puerto Rico with their grandparents right down the road.

Although Pura now spent most of her time writing, she still sometimes made appearances at the children’s story times that she had started as a librarian’s assistant years before. She was there today to read from her new collection of Puerto Rican folktales, called the The Tiger and the Rabbit and Other Tales. It was 1946, and it was the first English language collection of Puerto Rican folktales published in the United States.

Pura loved folktales because they are windows into how our ancestors made sense of the world around them and then passed those stories down to their children and grandchildren. By sharing folktales, different cultures and communities find common ground and understand how other cultures interpret universal themes like life, death, love, friendship, responsibility and the seasons. Early in her career at the Library, when Pura regularly hosted children’s storytime, she observed how exciting it was for her audience to see themselves in the stories sitting in the middle of New York City. She also found it was an effective way to share Puerto Rican culture with children of others races and ethnicities too.

Pura loved folktales because they are windows into how our ancestors made sense of the world around them and then passed those stories down to their children and grandchildren. By sharing folktales, different cultures and communities find common ground and understand how other cultures interpret universal themes like life, death, love, friendship, responsibility and the seasons. Early in her career at the Library, when Pura regularly hosted children’s storytime, she observed how exciting it was for her audience to see themselves in the stories sitting in the middle of New York City. She also found it was an effective way to share Puerto Rican culture with children of others races and ethnicities too.

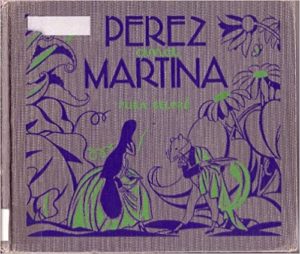

Pura hadn’t planned to be an author, but her love for folktales inspired her to seek out a publisher so in order to widely share them with a bigger audience. Her first published book was her written version of a folktale she grew up hearing from her grandmother: a love story between a cockroach and a mouse titled Pérez and Martina: a Portorican Folk Tale. When it was published in 1932, Pura became the first Puerto Rican author to publish an English language book with a major publishing house in the United States. Perez and Martina became a popular sensation. Pura recorded an oral version of the story that became a best selling record. She adapted it into a puppet show to bring it to life for Library storytime.

Pura leading story hour in the 1930s (New York Public LIbrary)

Pura kept writing. When she took a leave of absence from her job at the Library after marrying to travel with her musician husband, she found time to work on English language versions of other folk tales from her youth. When her leave was up, she decided to officially resign from her job at the Library and devote herself to her new project: a collection of Puerto Rican folktales. Her second story, The Three Magi, was published in the 1944 anthology The Animals’ Christmas. And from there, she put together her own collection of stories in The Tiger and the Rabbit and Other Tales.

The Power of the Wand

Pura believed in the power of storytelling to educate and inspire. The kids and teens participating in the National Youth Storytelling Showcase carry on her legacy every year. The Showcase is an annual event sponsored by Timpanogos Storytelling Institute in Lehi, Utah. It’s open to kids from ages 8-18 across the country to submit an electronic audition in the hopes of being selected as one of 18-20 youth storytellers to be featured in the Showcase. Visit them on the web to get inspired by the youth storytellers featured, like Darby Lynne Tassell from Kentucky. Darby has been a storyteller since she was 12 and was a NYSS Torchbearer (prize winner) in 2017. She has also been honored for her storytelling skills by the Kentucky Storytelling Association.

Her Yellow Brick Road

Pura moved to New York City when she was only a year out of high school. She, like hundreds of other young women immigrants, found her first job in the garment industry. She spent long shifts cutting and sewing. She quickly realized that she wanted to build a different career, and began exploring what other opportunities were available to her.

Pura (Bronx Library Center)

Pura studied English in high school and worked hard to become fluent, which proved to be a big advantage in her job search. Her sister had discovered that the New York Public Library needed bilingual employees to work with Spanish speaking immigrants. She turned down the job, but encouraged Pura to apply. Pura was hired as a Hispanic assistant at the Library’s 135th Street Branch in Harlem.

Literacy for all was a relatively new public goal in the United States at the turn of the 20th century. Before that, society did not prioritize literacy for the working classes. And most libraries were private institutions reserved for professionals or at colleges for tuition paying students. But as public schools became more commonplace, the need for access to libraries grew too. One of the biggest supporters of public libraries was steel industry millionaire Andrew Carnegie, who provided significant funding for the New York Public Library system, which opened in 1905. By 1920, Libraries were gaining notice as important spots for communities to gather and be creative. The Harlem Renaissance had sparked works of art and literature in Black community, and the 135th Street Branch was a central location for their growing collection.

Pura used puppets for her Spanish/English library storytimes. (Center for Puerto Rican Studies, Hunter College)

Pura spent much of her time working in the children’s division and quickly grew to prefer it to the adult sections. She ordered more Spanish language books for the library. She started a bilingual story time for Spanish speaking children to help them learn English and used puppets as a way to keep the kids’ attention. Pura began an inventory of the collection, reading all the books – many fairy tales – in the stacks. She searched for the stories she had heard growing up, but didn’t find any of them on the shelves. At the time, the Library policy was that any books read to children had to be from a published, written work. Pura wanted to share the folktales she grew up with as a child in Puerto Rico, believing they would be a wonderful bridge between their Puerto Rican culture and their new lives in New York.

After a few years as an assistant, Pura decided that she wanted to make a career of it. She enrolled in the New York Public Library’s Library School to train as an official librarian in 1926. Pura embraced all of her classes, but her favorite one was “The Art of Storytelling,” taught by Mary Gould Davis. Part of its curriculum covered folktales, stories passed on through oral tradition from generation to generation.

For a class assignment, Pura put one of her favorite childhood folktales into written form. Pura remembered sitting with her grandmother with rapt attention as she told the tale of a cockroach and a mouse who fall in love. She called the story Perez and Martina, after the two main characters. She asked Mary if she could read her written, but unpublished, tale to the children. Mary agreed, so long as she told them that “none of these stories have been written but maybe someday they will.” She brought Perez and Martina to story hour and read it to the children. They loved it, just as Pura had as a child.

Pura’s first published folktale – the 1932 first edition of Perez & Martina

During this time, like Pura, thousands of other Puerto Ricans arrived in New York City. They initially stayed with friends or family, and then moved to their own homes or apartments in the same area. As these Puerto Rican neighborhoods were established in various areas around the city, the Library worked to provide literacy services. In 1929, the Library moved Pura to the W. 115th Street branch in Southwest Harlem near a fast growing Puerto Rican neighborhood. Pura again was the lone Spanish speaking librarian translating and helping new immigrants navigate the library.

Pura again embraced her role as a bridge between the Puerto Rican community and the library. She became involved with local organizations that served Puerto Ricans in order to share the opportunities the library offered the community. She lobbied for more Spanish language books on the shelves, developed programming for traditional Puerto Rican holidays like Three Kings’ Day, and transformed the 115th Street branch into a cultural center. She made such a difference there that in the Library asked her to move to its East Harlem branch to develop similar programming for recent Spanish speaking arrivals in that part of town.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Pura grew up in Cidra, Puerto Rico, a small town located about 30 miles south of San Juan. Her childhood was a time for great change in Puerto Rico, which had been a Spanish colony since 1493. During the Spanish-American War of 1898, just before Pura was born, the United States invaded Puerto Rico and incorporated it as a United States territory. Pura grew up watching her family, friends, and neighbors lobbying and protesting the U.S. government for democratic rights. Their efforts prevailed, with the Jones Act of 1917 granting U.S. citizenship to all Puerto Ricans. This led to a large migration of Puerto Ricans to the United States mainland, particularly New York.

Pura grew up in Cidra, Puerto Rico, a small town located about 30 miles south of San Juan. Her childhood was a time for great change in Puerto Rico, which had been a Spanish colony since 1493. During the Spanish-American War of 1898, just before Pura was born, the United States invaded Puerto Rico and incorporated it as a United States territory. Pura grew up watching her family, friends, and neighbors lobbying and protesting the U.S. government for democratic rights. Their efforts prevailed, with the Jones Act of 1917 granting U.S. citizenship to all Puerto Ricans. This led to a large migration of Puerto Ricans to the United States mainland, particularly New York.

Her family moved around frequently with her dad’s job as a building contractor. Pura attended the public high school in Santurce, a town just a few miles from San Juan along the coast. She graduated in 1919 and enrolled at the University of Puerto Rico in Río Piedras. Although Pura planned to get her degree and settle in Puerto Rico, she ended up completing only one year of college. Her sister Elisa had moved to New York City and sent word home that she was getting married. Pura, who had recently finished her freshman year in college, went to New York for the wedding in 1920. She loved the energy and opportunity New York City represented and decided to stay.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- There are three dates in the historical record for Pura’s birthday: February 2, 1899, December 2, 1901, and February 2, 1903.

- In 1940, Pura travelled to Cincinnati, Ohio for an American Library Association conference. She was there to present her experiences building library services for Spanish language speakers. Her talk was a success, and she also met Clarence Cameron White, a well-known Black composer and violinist who was conducting a music festival there at the same time. Pura and Clarence fell in love and married on December 26, 1943.

- Pura and hubby kept their main residence in Harlem. After her hubby died of cancer in 1960, Pura asked the Library if she could return to working as a Spanish Children’s Specialist. She went back part-time to preserve time for her writing. She became a traveling librarian, moving around the city to neighborhoods with lots of Puerto Rican families.

- Pura retired from the New York Public Library in 1968. The founders of the South Bronx Library Project asked her to work with them to deliver library services to Spanish speaking neighborhoods. She helped stage events at local buildings and driving a mobile library around in a van and coordinated the South Bronx Puppet Theater.

- Pura was a member of the Association for the Advancement of Puerto Rican People, co-founder of the Archivo de Documentación Puertorriqueña, a group dedicated to collecting original Puerto Rican documents and helped develop children’s programs at the Museo del Barrio.

- During Pura’s time in New York City, the number of Puerto Rican immigrants accelerated from about 7300 in 1920 to 612,000 by 1960. In 1952, Puerto Rico became a Commonwealth of the United States.

- The Library’s 135th Street Branch in Harlem is now the well-known Schomburg Center. It was renamed in 1962.

- Pura died on July 1, 1982. Her papers were left to the Center for Puerto Rican Studies at Hunter College in New York City.

- The Pura Belpre Award was established in 1996. It is awarded annually to “a Latino/Latina writer and illustrator whose work best portrays, affirms, and celebrates the Latino cultural experience in an outstanding work of literature for children and youth.”

Want to Know More?

Jimenez, Marilisa. “Pura Belpré Lights the Storyteller’s Candle: Reframing the Legacy of

a Legend and What it Means for the Fields of Latino/a Studies and Children’s Literature” (Centro Journal Jan. 2014).

Nuñez, Dr. Victoria. “Remembering Pura Belpré’s early career at the 135st New York Public Library” (Centro Journal 2009).

Nuñez, Dr. Victoria. “Pura Belpré: Centro Teaching Guide” (Center for Puerto Rican Studies, Hunter College CUNY).

Staff. “Pura Belpré Biographical Essay” (Center for Puerto Rican Studies, Hunter College CUNY)

Staff. “Pura Belpré Award” (Center for Puerto Rican Studies, Hunter College CUNY).

Ulaby, Neda. “How NYC’s First Puerto Rican Librarian Brought Spanish to the Shelves” (NPR Sept. 8, 2016),