Passionate Patriot

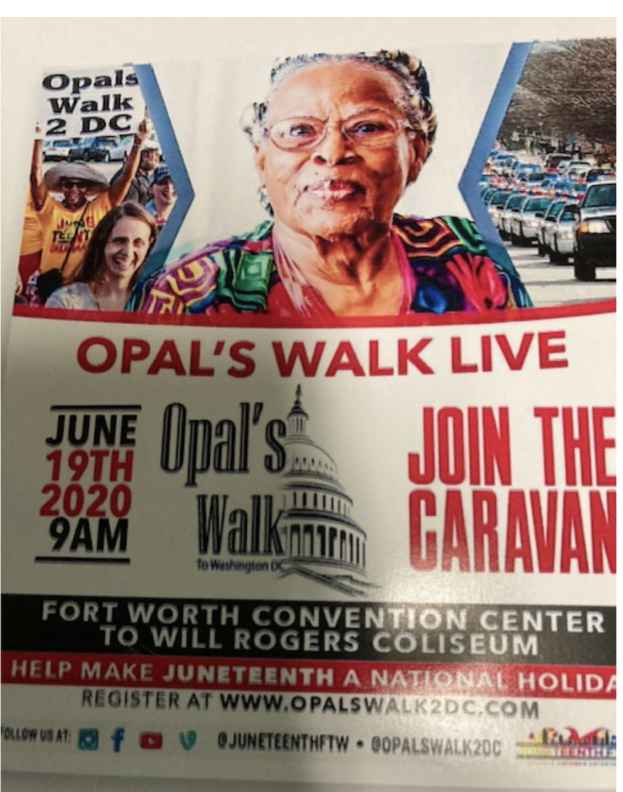

She was a teacher and volunteer determined to see Juneteenth become a national holiday in her lifetime. So she decided to walk from Fort Worth, Texas to Washington, D.C. 2.5 miles at a time to draw attention to her cause…at age 90! Along the way she shared her vision of a freedom season – that Juneteenth is part of the promise set out in the Declaration of Independence.

Her decision sparked the momentum that led to her standing at the White House as the Juneteenth bill was signed. Walk back to June 17, 2021 and meet the “Grandmother of Juneteenth,” Opal Lee…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

Opal Lee watched with joy as President Biden sign the bill that, once and for all, made Juneteenth a national holiday. It would now be officially on the calendar, to be celebrated in the from sea to shining sea. For years, Opal envisioned a freedom season – a national celebration starting with June 19th and leading up to Independence Day on July 4th. And she had been working for decades to make it happen. She smiled as she reflected on her hard earned nickname: the “Grandmother of Juneteenth.”

Opal began her walk to Washington, D.C. on September 1, 2016. (Opal’s Walk: The Life and Works of Opal Flake Roland Lee)

Opal loved teaching the history of Juneteenth, and explaining its important place in the American story. In the midst of the Civil War, on January 1, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, declaring that “all persons held as slaves” within the rebel states “are, and henceforward shall be free.” But until the Union Army started marching through the Confederacy in mid-1864, freeing the enslaved along the way, most enslaved people did not know about it.

The Civil War officially ended in April 1865, but it it took some time for the Union Army to reach the farthest western part of the Confederacy – Texas. On June 19, 1865, Major General Gordon Granger arrived in Galveston, Texas. He gathered the townspeople together at the Strand Hotel where he read General Order Number 3, which declared that the Emancipation Proclamation would be enforced in Texas and all enslaved people were, from that moment, free. Major Granger then nailed the Order to the front door of the Reedy Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church. The crowd at the church grew as the enslaved field workers came in for the day and heard the news. In their jubilation, they created a name for this glorious day: Juneteenth.

One year later, on June 19, 1866, there were celebrations all over Texas to celebrated the anniversary of freedom. While they differed from town to town, most involved some combination of church services, picnics, music and speeches. An annual tradition was born.

In 1970s Fort Worth, the Black History & Genealogical Society took charge of Juneteenth. Opal was on the Board and eventually became the point person for the celebrations. For the next 40 years, Opal was a key organizer of the Fort Worth celebrations, and, in the 1990s, joined the movement to get national holiday status.

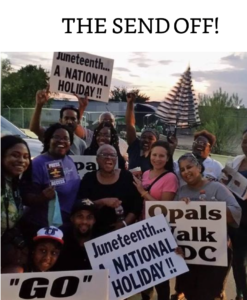

Opal turned 90 in 2016 and knew that she only had so much time left to make her dream a reality. It was time to do something really big to draw attention to Juneteenth. So she decided to walk 1400 miles from Fort Worth to Washington, D.C. – 2.5 miles at a time, to symbolize the 2.5 years it took for news of the Emancipation Proclamation to reach Texas.

Opal, joined by family and friends, left from her church in September 2016, walking 2.5 miles twice a day, morning and evening. While she initially had a donated RV accompanying her, the donor worried Opal’s quest was too political and took it back. There were some people who feared Opal trying to replace Independence Day. But Opal explained that this was simply a way to expand the story of freedom and the promise of the Declaration of Independence, not take anything away.

Without the RV, Opal adjusted her plans and traveled to towns along the route where Juneteenth was celebrated, walking with townspeople to demonstrate how beloved this day already was in many places. As Opal spread the joy of Juneteenth, more people understood and joined her efforts. Soon towns who wanted to learn more were requesting that she visit and walk with them too.

Opal, on the left next to Vice President Harris, witnessing the signing of the Juneteenth legislation (Wikimedia Commons)

On June 10, 2017, Opal finally arrived in Washington, D.C. Her Congressman arranged a press conference and tour…but the vote to designate Juneteenth as a national holiday failed. Opal returned home defeated but not ready to quit. She continued visiting cities all over the country where she walked and talked about Juneteenth. She collected 1.5 million signatures for a petition.

It took another four years, but Opal finally got the call she had been waiting for from the White House. The Juneteenth bill was coming up for a vote again and it was expected to pass. And it did pass, unanimously, the Senate on June 15, 2021 and the House the following day. Opal stood next to President Biden as he signed the bill on June 17, 2021 and he gave her the pen to keep. Opal reflected that “at 94, to have Juneteenth made a National holiday in my lifetime is unbelievable…I could do a holy dance.”

The Power of the Wand

In addition to her individual efforts, Opal served on the Board of the National Juneteenth Observation Foundation, and is an honorary national co-chair of the Juneteenth Legacy Project.

Opal wants her example to inspire others to make change: “I don’t know if I’ve gotten over the fact that each one of us needs to be responsible for making our country the country it needs to be…We can’t leave it to the government and to other people to do it. Make ourselves a committee of one to address the things that are happening that we know can be erased. That’s all I need to see. I hope people will listen that we can do this.”

Her Yellow Brick Road

By the time Opal was 21, she had four kids and a failing marriage. She supported their family by working nights as a powder room attendant at a nightclub. When her youngest was one month old, she left her husband and moved into her mom’s house. Her mom had been devastated when Opal got married instead of going to college, so she offered to babysit while Opal worked to earn enough money for tuition.

During Opal’s years at Wiley College, she spent the week at school attending classes, working in the student bookstore, and cleaning houses. On weekends she went home to see her kids and work nights. It was a tough road, but she made it through and graduated in June 1953 with an education degree.

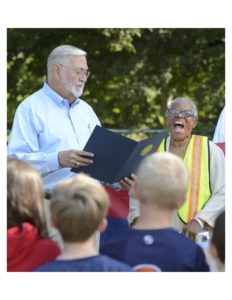

Opal at one of her stops during her 2016 walk to Washington, D.C. (Brian D. Sanderford Times Record)

Opal’s post-college life was just as busy. She taught 3rd grade all day, went home to see her children, and then worked nights as a maid at an aerospace company. After four years, she found a new evening job running a small newspaper – and was able to save enough money for a down payment on a house of her own.

Opal’s approach to teaching was to be strict but fun (she joked that she often adopted the 8 year old mindset of her students). She had a big heart for the kids who came to school without the basics – proper clothing and shoes, enough to eat, soap and toothpaste. This made her the perfect fit when her school district asked her to fill a new role dedicated to helping students in crisis.

Opal agreed to become the “visiting teacher.” She spent the next 10 years serving all of the district schools. She tracked down students who had chronic absences, found out why, and tried to help get them back to school. She often had as many as 500 kids on her caseload – which she told her superintendent was too many. He agreed, but said there was no budget for more help, so she would have to handle it. And she did. Opal retired from teaching in 1977, but not from helping others. Her main concerns remained what she had seen with her students – the need for healthy food and a place to live.

Opal now had time to tackle the unsanitary conditions she had witnessed for years at the local food bank. She got on the board, recruited new members, and led a movement to replace the CEO. When its building burned down, she negotiated with a nearby guacamole factory to temporarily store food for a reasonable rent. The factory owners were so impressed by how many people were helped that they donated the building.

Opal also founded “Opal’s Farm” with 13 acres of donated farmland on the Trinity River. She recruited an army of volunteers to fundraise, get seed donations, and train the ex-convicts the Farm hired to work there. The project combined many of Opal’s goals – help people find work and have healthy food to eat.

Opal also founded “Opal’s Farm” with 13 acres of donated farmland on the Trinity River. She recruited an army of volunteers to fundraise, get seed donations, and train the ex-convicts the Farm hired to work there. The project combined many of Opal’s goals – help people find work and have healthy food to eat.

Opal was one of the founders of Citizens Concerned with Human Dignity, an organization devoted to helping families find stable housing. And when she saw that there simply wasn’t enough affordable housing in the area, she pitched in to help Habitat for Humanity create it.

The same year Opal retired from teaching, a local woman, Leonora Rolla, founded the Black History & Genealogical Society. Leonora was inspired to do so after being appointed to the planning committee for Fort Worth’s 175th birthday. She wanted to incorporate Black history into the celebration, but those stories were difficult to find. Her solution was to create a place where that history would be shared and celebrated.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Opal spent her first nine years in Marshall, Texas. Her mom, Mattie Broadus, was from one of the biggest families in Texas, and had 18 brothers and sisters! Marshall had a reputation for excellent schools for Black citizens and was also the home of Wiley College. Mattie moved there for high school, where she met Opal’s dad, Otis.

Opal’s walks became a phenomenon. (Opal’s Walk: The Life and Works of Opal Flake Roland Lee)

Opal grew up with two younger brothers. When Opal was 7, their family home burned down. Her parents built a small shelter on the land while they decided what to do next. Money was tight and they weren’t sure they should rebuild in Marshall. Otis went to Fort Worth to see if there were better prospects there. He found a job and sent for Mattie and the kids. They sold their only cow and most of their possessions to pay for their fare to Fort Worth. They arrived on a Saturday and her mom started working as a cook for a white family on Sunday. Opal was 9 and started attending the local elementary school.

Over the next three years, her family moved 17 times When Opal was 12, her mom fell on a city bus and received a settlement for her injuries. Her parents used the money to put a down payment on a house, and were hopeful this would finally allow them to put down roots in Fort Worth. They didn’t anticipate the violent reaction the white neighbors would have to a Black family moving on to their street. A mob gathered while her parents were at the house, and they had to flee as the mob set the house on fire.

Two years later they were able to afford another house, this time buying in a Black neighborhood. Opal, now a student at I.M. Terrell High School, enjoyed her classes, made good grades, and was on track for college. Her mom’s dream was for Opal to return to Marshall to attend Wiley College after graduation, and was determined to make that happen even after she and Opal’s dad divorced and he moved away. But Opal had fallen in love with a boy at school named Joe Thomas Roland. They got married right after her 1943 high school graduation, just before Opal turned 17.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- Opal Flake was born on October 7, 1926 in Marshall, Texas.

- Opal earned her Master’s degree in Educational Counseling & Guidance from North Texas State University in 1962.

- Opal married Dale Lee in 1967. They had a happy 30 year marriage until his death.

- Fort Worth Juneteenth Celebrations are now produced by United Unlimited, a non-profit organization run by Opal’s granddaughter.

- Opal was nominated for the 2022 Nobel Peace Prize.

- Opal has a special New Year’s Day tradition – every year she invites all her relatives, friends, and associates to dinner at her home in Fort Worth.

- In the 1990s, four more states made it official (Texas, Florida, Oklahoma, Minnesota). As the national movement got rolling at the turn of the century, other states The national movement started then, and by 2016, 45 states recognized with ore states recognizing Juneteenth by 2010, and up to 45 total by 2016.

- Opal inspired the “Freedom Collection” clothing line. She worked with Unity Unlimited and the WCN.

- Opal wrote Juneteenth: A Children’s Story in 2019 and recently released an updated version.

Want to Know More?

Howard, Renetta T. The Life and Works of Opal Flake Roland Lee (April 16, 2021).

Robinson, Cheryl. “Opal Lee, Grandmother of Juneteenth, Shares the Importance of Using Your Voice to Activate Change” (Forbes June 19, 2022).

The Juneteenth Legacy Project.

The Emancipation Proclamation (National Archives).

Juneteenth Fact Sheet (Congressional Research Service updated May 30, 2023).