Super Scientist

As she was growing up, she “helped” her father with his job as a soil surveyor. She wanted to follow in his footsteps, but assumed that it wouldn’t be an option because she was a woman. But then she was accepted into a masters program in geology, in part because most of the men were fighting overseas in World War II. She eventually landed her dream job and made scientific history when she created detailed maps of the ocean’s floor. Step back to Columbia University in 1952 and meet Marie Tharp …

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

Marie Tharp sat in the empty geophysics lab at Columbia University. It was Spring, 1952 and she was fed up with the inequality at the lab. While all her male colleagues were in Brussels for a conference, Marie decided to leave New York and return to her family’s farm in Ohio.

By then, Marie had worked at the geophysics lab for 4 years. She was hired as a “general drafter” and assisted the male scientists with drawing diagrams and calculating math equations. She did work for anyone who requested help, toggling from scientist to scientist and project to project. The work was easy for her, however, and not very fulfilling.

Marie Tharp (Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory)

Meanwhile, Marie’s absence was felt acutely back at Columbia. So Dr. Ewing, director of the Lamont Geological Observatory, sent her a telegram asking her to come back from her “extended vacation.” Marie thought about the offer for a few days, and decided she wanted to go back to work.

When Marie returned to the lab, she no longer supported all the scientists. Instead, she was teamed up with Bruce Heezen. It was the start of a 30 year partnership, and they worked together to map the floor of all the oceans on earth. A few days after they started working together, Bruce gave Marie five years worth of sonar recordings — there were boxes and boxes of paper rolls, on which countless ocean depth measurements were recorded. Marie was instantly captivated.

Over the next 6 months, Marie plotted about 3,000 feet of sonar recordings. The data represented 300,000 miles of travel from multiple ocean voyages. So she cut them all up and put them back together based on latitude and longitude — it was a giant puzzle. She was meticulous in her analysis of the data, working for hours at a time alone in her home. By the time Marie was done, she had 6 different lines of data that crossed the Atlantic. While she worked with the past data, Bruce collected new sonar recordings at sea to fill any gaps in the data.

Over the next 6 months, Marie plotted about 3,000 feet of sonar recordings. The data represented 300,000 miles of travel from multiple ocean voyages. So she cut them all up and put them back together based on latitude and longitude — it was a giant puzzle. She was meticulous in her analysis of the data, working for hours at a time alone in her home. By the time Marie was done, she had 6 different lines of data that crossed the Atlantic. While she worked with the past data, Bruce collected new sonar recordings at sea to fill any gaps in the data.

Marie’s next step was to plot all the data onto a map. Unfortunately, no map existed that was big enough to plot so much data. So she made one. Marie didn’t just make a two dimensional map, however. She made a “Physiographic Diagram” to show a 3D image of the ocean floor, portraying different land features by thick and thin cross hatching (rather than just a topographical line). As she went along, Marie started to notice some patterns. She used the patterns to make educated guesses where there were gaps in the data.

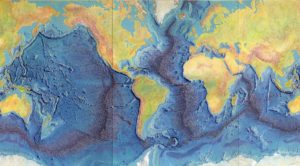

Slowly, a visual of the ocean’s floor emerged. And it wasn’t flat. The data showed that the ocean floor was filled with ridges, valleys, mountains ranges and deep gorges. Even more, Marie’s map showed a deep valley, or rift, ran the length of the Atlantic Ocean and cut the ocean in half, where one continental plate ended and another began. Eventually, Marie and Bruce discovered a similar rift in most oceans — up to 2 miles deep, 20 miles wide, and 40,000 miles in total (the Mid-Oceanic Rift).

Marie Tharp’s map of the ocean floor

Marie and Bruce’s discovery of the Mid-Oceanic Rift was controversial within the scientific community. It lent credence to the theory of “continental drift,” which was considered wild conjecture at the time. However, Marie’s attention to detail gave the project credibility and made it hard to refute her revolutionary findings.

Marie and Bruce hired Heinrich Berann, an Austrian artist, to paint their maps in preparation for publication in National Geographic. They completed the first map of the Atlantic Ocean floor in 1957, which was published in 1960. After that, they moved on to the South Atlantic Ocean (including the Caribbean), the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean. By 1977, they had published maps of nearly every ocean floor around the world.

The Power of the Wand

Marie Tharpe quietly changed the scientific world. The research she and Bruce conducted, as well as the maps they created, paved the way for the theories of plate tectonics and continental drift — a paradigm shift in earth science.

Her Yellow Brick Road

Marie arrived in Ann Arbor in the middle of a snowstorm in January, 1943. And she was quickly immersed in the field of geology. The master’s program was an intense two year program. At first, she was overwhelmed at the learning curve but quickly settled in.

Most of the other enrollees were women as well, since it was the middle of World War II — they were called PG Girls, or petroleum geology girls. Marie spent her summers doing field work, studying geological formations out West. While at Michigan, Marie became curious about how the surface of the earth was formed. Her professors fostered her curiosity and introduced her to the fringe theory of “continental drift.”

Marie Tharp at her drafting table (Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory )

Marie graduated with a master’s degree in Geology in 1945. However, she stayed an extra semester to take some physics and chemistry classes. She took an interdisciplinary approach to her education and wanted to fill some of the gaps in her education. It was an unusual approach at the time and her professors worried that she was too scattered.

But then, she received a job offer at Stanolind Oil & Gas Company in Tulsa, Oklahoma. And she took it. She was an assistant to a senior geologist — she filed papers, found maps of drilling sites, and researched drilling locations and depths. It was easy work, however, and she quickly grew bored. So she went back to school while working full time. She took evening classes and earned a mathematics degree from the University of Oklahoma. Then, her 3 year commitment ended in August, 1948, and Marie decided it was time to move on.

While living in Tulsa, she traveled home to marry her high school sweetheart, David Flanagan. He played the violin and was offered a position at Juillard, son they both moved to New York City. Then, they divorced a few years later.

While living in Tulsa, she traveled home to marry her high school sweetheart, David Flanagan. He played the violin and was offered a position at Juillard, son they both moved to New York City. Then, they divorced a few years later.

When Marie arrived in New York City, she wasted no time looking for a job. She went to the geology department at Columbia University on a rainy, gray November 1, 1948. Dr. Ewing, the head of the department, was on a research trip, however. So she returned two weeks later and Dr. Ewing agreed to give her an entry job in his geophysics lab.

Marie was hired as a research assistant at the Lamont Geological Observatory. She was a “drafter” and supported all the men in the lab — she hand copied maps, gathered data, and did countless math calculations. Marie worked long hours and grew frustrated. She was more highly educated than everyone else in the department, but was stuck doing secretarial work. And she had a deep desire to utilize all her skills and education, doing the same work as the men in the lab.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Marie moved around a lot while she grew up. She was lonely as a child and felt like an outsider much of the the. She attended more than 15 schools by the time she graduated from high school.

Marie’s dad was a soil surveyor for the US Department of Agriculture’s Bureau of Soils and was stationed throughout the Midwest and South. He surveyed land for farmers, so they understood the different types of soil on their land and crops that would thrive in each. At times, Marie joined her dad on the job — she helped him measure the land, collect soil samples, and make maps for farmers.

Marie Tharp (Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory)

After her dad retired, the small family settled on a farm in Ohio. It was Marie’s first permanent home. Unfortunately, her mom died about one year later. Marie graduated from high school in 1938, then took a year off to help her father with the farm.

Marie loved the work her father did, but assumed it wasn’t an option because she was a girl. Instead, she planned to follow in her mother’s footsteps and become a teacher. So she started at Ohio University in Athens in fall of 1939. Marie tried a lot of different classes — art, music, English, education, German, zoology, paleobotany, and philosophy — but nothing was the right fit.

Then, Marie found geology. She was captivated by what she learned in her geology classes. However, her college mentor suggested that she also focus on cartography. The reality was that, as a woman, Marie wouldn’t be allowed out in the field. So she needed to focus on the tasks within geology that would be accessible to her. In her drafting class, Marie learned how to visualize and present topography of the land.

When Marie was a senior in college, she saw a flyer for an accelerated Master’s geology degree from the University of Michigan. Graduates were guaranteed a job in the petroleum industry. And she was intrigued. Usually, the program only accepted men. But few men were enrolled since it was the middle of World War 2. So she seized the opportunity and applied.

In December of 1943, Marie asked and received approval from Ohio University to graduate early (she had more than enough credits). She earned a bachelor’s degree in the areas of English and Music, with four minors (including geology). Then, she packed her bags.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- Marie Tharp was born on July 30, 1920 in Ypsilanti, Michigan. Her father worked for the US Department of Agriculture’s Bureau of Soils and her mother taught German and Latin. Marie had a half-brother named Jim, from her father’s first marriage.

- Marie earned degrees from Ohio University, University of Michigan, and University of Oklahoma.

- Marie worked at the Lamont Geological Observatory for nearly 30 years and was a member of the faculty at Columbia University until 1983.

- In 1956, Marie’s revolutionary findings were originally published in a paper called “Some Problems of Antarctic Submarine Geology.” Bruce Hezeen and Dr. Ewing were listed as authors of the paper. Marie’s name was excluded from the paper, however, because she was a woman.

- Marie wasn’t allowed to accompany Bruce on fact gathering missions because women weren’t allowed on ships until the 1960s (they were considered bad luck to be aboard).

- Marie and Bruce’s maps of the ocean floors were published in National Geographic between 1960-1977.

- Marie and Bruce started a romantic relationship at some point. She was devastated when he passed away in 1977. He died of a heart attack when they were on a scientific research trip (he was in a submarine and she was on a ship, right above him). After he died, she finished their work and then retired to operate a map business out of her home. She donated Bruce’s papers to the Smithsonian Institution.

- Marie received the following awards: Lamont-Doherty Heritage Award; recognition by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and the Library of Congress Geography and Map division.

- Marie died on August 23, 2006.

- In 2023, the US Navy honored her by naming one of their ships the USS Marie Tharp.

Want to Know More?

“Hazen-Tharp Collection” at the Library of Congress.

“About Marie Tharp.” Lamont Geological Laboratory (now the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory at Columbia University (https://marietharp.ldeo.columbia.edu/about-marie-tharp).

Felt, Hali. Soundings: The Story of the Remarkable Woman Who Mapped the Ocean Floor. (New York: Henry Holt & Co, 2012).

“Earth 520: Plate Tectonics and People. Marie Thorp.” Penn State University, College of Earth and Mineral Sciences (https://www.e-education.psu.edu/earth520/node/1797).