Inspiring Inventors

She spent years developing a machine to mass produce flat bottomed grocery bags, only to have her invention stolen by a man who claimed that no woman could build something so sophisticated. She took him to court, won, and started a business that changed the way people shop forever. Step into a 1871 Washington D.C. courtroom and meet Margaret Knight…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

Margaret Knight marched into the Patent Office Building in Washington DC. It was February of 1871 and she was due in court later that morning before the Commissioner of Patents. Margaret was determined to convince the Commissioner that she was the true owner of her most recent invention — a machine that cut, folded and glued a sheet of paper into a flat-bottom bag. And that they had erroneously issued a patent to the man who stole her idea.

Margaret had filed a patent application for her paper bag machine about one year earlier — it included nine illustrations, over two pages of explanation, and her iron model. But to her dismay, her application was denied. She was informed that a patent had already been issued to Mr. Charles Annan for a similar machine.

Model of Margaret’s paper bag machine, Smithsonian Institution

Margaret was stunned. How could this have happened? She had spent years on her invention. But she didn’t give up. Margaret thought that the name “Annan” sounded familiar. She got a copy of his patent and noticed that Annan’s machine looked suspiciously similar to her own. Then, she remembered Annan from one of the iron foundries she worked with in Boston. And the pieces all came together — Annan stole her idea, copied her design, and lied on his patent application. So she took him to court.

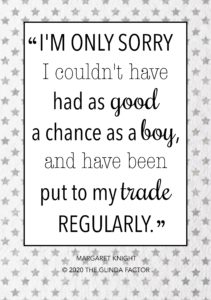

Margaret hired a lawyer and arrived in DC with all her notebooks, diaries, photos, patterns, models, records, machine and completed bags. She also asked a number of people to testify on her behalf, including the ironworkers who worked on her machine. Annan didn’t have much of a defense — he just said that no woman could have the knowledge to build such a sophisticated machine!

Three weeks later, Margaret’s hard work finally paid off. After 16 long days of testimony, Margaret convinced the Commissioner of Patents that she should be granted a patent for her paper bag machine. And she became the first woman in American history to win a patent interference lawsuit.

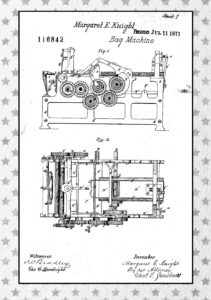

Margaret’s patent application

It took two years of development, one application denial, and a lawsuit for Margaret to accomplish her goal. On Tuesday, July 11, 1871, she was finally awarded Patent No. 116,842 for her Paper Bag Machine.

After receiving her patent, Margaret and a business partner created the Eastern Paper Bag Company. It was based in Hartford, Connecticut and manufactured flat-bottom paper bags using her patented machines. Margaret quickly realized that the hardest aspect of managing the factory was supervising her male employees. She had to convince them to follow her instructions while installing the equipment — they didn’t believe that she was capable of having any mechanical knowledge.

Margaret continued to aggressively enforce her rights as an inventor — the Eastern Paper Bag Company sued a rival company to prevent the use of its patent. And won. The case went all the way up to the US Supreme Court in 1908. In Continental Paper Bag Company v. Eastern Paper Bag Company, the Supreme Court ruled that a company may enforce its rights as a patent owner, even if it isn’t currently using the patent. The decision is still a critical principle of patent law today.

The Power of the Wand

It may not sound very impressive today, but Margaret’s invention revolutionized how America stored and transported all kinds of items. Before that, shop owners used various methods to package items (paper and twine, large paper cones, gunny sacks and heavy wooden crates). Businesses across America immediately saw the benefit of Margaret’s flat-bottom bags and have been using them ever since (now they’re called “Self-Opening Sack” or SOS bags).

Any bag that can stand upright on its own is based on Margaret’s design. SOS bags are found everywhere, literally — grocery stores, restaurants, department stores, clothing stores, and hundreds of prepackaged items. Today, more than 7,000 machines produce flat-bottom paper bags around the world. And they all still use Margaret’s basic concept.

Margaret was the first professional woman inventor in America. And she was determined to protect her work, receiving over 20 patents during her lifetime. Many women have followed in her footsteps over the years. For example, Ann Makosinski created the Hollow Flashlight when she was 15 years old. It is powered by “thermoelectrics” and won the 2013 Google Science Fair. Her inspiration came when she learned that high school students in the Philippines couldn’t do any homework after dark. Her goal was to bring light to people who didn’t have access to electricity or batteries. Anyone, wherever they are in the world, can activate the Hollow Flashlight simply by holding it in their hand.

Her Yellow Brick Road

Margaret was working at the Columbia Paper Bag Company in Springfield, Massachusetts when the idea came to her. She took a job as a bag bundler in 1867, packaging the Company’s envelope bags for shipment to customers. The Company mass produced envelope bags by machine, but hired workers to make flat-bottom bags by hand, one at a time. As a result, the flat-bottom bags were an expensive luxury.

It didn’t take Margaret long to realize that flat-bottom bags were the better design. And she was surprised that no machine existed to make them. So she invented one. She sketched ideas in her notebook and had a design on paper within a few months.

Then, Margaret made a few prototypes of her design. She started by adapting an existing envelope bag machine — and it worked! Then, she built a wooden model of her machine. It took about six months and was completed in July of 1868. It could cut, glue, and fold a flat-bottomed paper bag with the turn of a crank. Even though the wooden machine was a bit rickety, it successfully made one bag after another.

Then, Margaret made a few prototypes of her design. She started by adapting an existing envelope bag machine — and it worked! Then, she built a wooden model of her machine. It took about six months and was completed in July of 1868. It could cut, glue, and fold a flat-bottomed paper bag with the turn of a crank. Even though the wooden machine was a bit rickety, it successfully made one bag after another.

Finally, Margaret used her wooden model to make patterns for an iron machine. She wasn’t a machinist and didn’t work with iron on a regular basis, so she hired a local ironworker to do the work. When the iron machine was completed a few months later, she destroyed the wooden model so no one could copy it. And she made thousands of paper bags from it. But Margaret knew it could be better.

Margaret brought her model to Boston to seek a little more expertise. She hired two different machinists to make some improvements to her design based on her specifications. Another machinist named Charles Annan saw Margaret’s machine in the shop. He said he was curious about how it worked, asked a lot of questions, and requested a demonstration. But then, Annan stole Margaret’s idea.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Margaret grew up in New Hampshire, right before the Industrial Revolution changed America. She had a mechanical mind from an early age — she built toys for her siblings to play with, such as kites and sleds. And her family supported her interest in machines and how they worked, Margaret’s dad died when she was young and she inherited her father’s tool chest, which she used for the rest of her life.

After her father died, Margaret did her part to support the family. She left school around age 11 to work at the Amoskeag Manufacturing Company, a cotton mill in Manchester, New Hampshire. Her whole family (mom and two brothers) worked 13 hour days at the same factory.

After her father died, Margaret did her part to support the family. She left school around age 11 to work at the Amoskeag Manufacturing Company, a cotton mill in Manchester, New Hampshire. Her whole family (mom and two brothers) worked 13 hour days at the same factory.

One day, Margaret witnessed an accident at the factory — the piece of a loom broke off, flew through the air, and stabbed a young boy, who died as a result. The broken piece was a shuttle, which was used to weave the thread through the loom. Margaret couldn’t get the image of the injured boy out of her mind. And she never wanted to witness an accident like that again.

So Margaret invented a safety device that would prevent such accidents in the future. Her invention shut down the machine automatically if it malfunctioned. Before long, Margaret’s invention was adopted by cotton mills across the country (she never received any money for her invention). And she went on to invent many items that improved people’s lives over the years.

Glinda’s Gallery

Visit Margaret’s digital scrapbook on Pinterest: https://www.pinterest.com/theglindafactor/margaret-knight/

Just the Facts

- Margaret was born in York, Maine on February 14, 1838. She never married.

- Margaret’s nickname was “Lady Edison.”

- Margaret was awarded over 20 patents during her lifetime. A few examples of her other patents include: skirt protector, robe clasp, shoe manufacturing machines, rotary engine improvements, roasting spit, and window designs.

- The patent model of her paper bag machine is at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

- She was given the decoration of the Royal Legion of Honor by Queen Victoria in 1871. She was also inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2006.

- Some people say that Margaret invented over 80 items, but many were owned by her various employers over the years (so she didn’t receive any royalties). In 1913, the New York Times reported that, at 70 years old Margaret “is working twenty hours a day on her 89th invention.”

- Margaret died on October 12, 1914 in Framingham, Massachusetts at age 76. She continued inventing new items until the day she died. Unfortunately, Margaret wasn’t as talented with the business side of things — she died with only $275 to her name.

Want to Know More?

“Improvement in Paper-Bag Machines,” Letters Patent No. 116,842, dated July 11, 1871. United Stated Patent Office.

“Paper-Bag Machine,” Letters Patent No. 220,925, dated October 28, 1879. United States Patent Office.

Knight v. Annan. February 20, 1871, pp 34-39. Decisions of the Commissioner of Patents for the Year 1871 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1872).

Continental Paper Bag Co. v. Eastern Paper Bag Co., 210 U.S. 405 (1908) (https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/210/405/).

Merritt, Deborah. “Hypatia in the Patent Office: Women Inventors and the Law, 1845-1900.” The American Journal of Legal History. Vol. 35, No. 3 (July 1991), pp. 235-306.

Smith, Ryan. “Meet the Female Inventor Behind Mass-Market Paper Bags.” Smithsonian Magazine. March 15, 2018 (https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/meet-female-inventor-behind-mass-market-paper-bags-180968469/)

Famous Women Inventors (http://www.women-inventors.com/Margaret-Knight.asp)