Amazing Artist

She grew up helping her father with his photography hobby, tinkering with different lenses and developing photographs in the bathtub. After he passed away, she turned their hobby into a career and specialized in capturing the giant machines used in America’s industrial factories. While she was a war correspondent for “Life” magazine during World War II, she witnessed and documented the horrors of the Holocaust. March back to 1945 and meet Margaret Bourke-White…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

Margaret Bourke-White’s senses were overwhelmed by the horror she saw before her. It was April 11, 1945 and she arrived at the Buchenwald concentration camp with General George Patton’s Third Army. It was one of the first concentration camps that US Army liberated as it traveled through Germany.

Patton and his troops arrived at Buchenwald just hours after the last Nazis left. And he was so enraged by what he saw that he ordered his men to round up the German citizens who lived in the nearby town, Weimer. He refused to believe that they had no idea what was going on in their backyard, and wanted them to face the crimes committed by their country.

Margaret at Buchenwald (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Courtesy of Patricia A. Yingst)

Margaret arrived about the same time as the German citizens walked into the camp. She immediately unpacked her photography equipment and focused on her job. The scene before her was so horrific that it helped to view it all from behind the lens of her camera. She knew that an atrocity of this magnitude had to be documented, regardless of how difficult it was.

Margaret forced herself to photograph everything she saw. She captured the vacant stares of the emaciated prisoners who survived. She recorded the reactions of German citizens who were forced to face the horror. She photographed the remains of murdered prisoners. And she documented the camp itself, including the machines of destruction such as the cremation ovens and gas chambers.

LIFE magazine published Margaret’s photographs of Buchenwald and other concentration camps, which stunned the American public. At the time, few Americans knew the magnitude of Hitler’s murderous campaign against the Jews, the so-called Final Solution. Her haunting images shed light on the atrocities and made it impossible to ignore the Holocaust any longer.

When Margaret returned to America, she couldn’t get the scenes from the concentration camps out of her mind. She was haunted by the images and had lost her faith in humankind. So she decided to write down her feelings and memories, to help make sense of the horror. Margaret’s book, Dear Fatherland, Rest Quietly, was published in 1946.

The Power of the Wand

Margaret Bourke-White was the first woman accredited by the US Army to work in combat zones during World War II. And she was a pioneer in photojournalism and industrial photography. Her independence and drive has been an inspiration to future generations of women photographers.

Her Yellow Brick Road

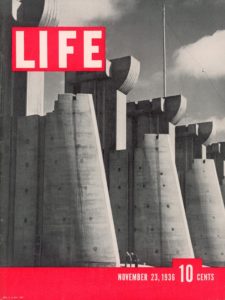

Margaret’s photo of Fort Peck Dam on cover of first issue of LIFE magazine

Margaret arrived in Cleveland after college, determined to make her mark. At first, she worked for various architect firms and photographed the homes and office buildings designed by them. But Cleveland’s burgeoning manufacturing businesses called to her. Day after day, Margaret roamed through town and photographed its docks, factories trains, smokestacks, pipes and bridges. She loved taking industrial photographs, in part because it made her feel closer to her father. In addition, she was drawn to the massive scale of the steel plants, the repeating patterns in machinery, and how the steam softened the harsh industrial landscape.

Before long, Margaret’s work became noticed by magazines and corporations alike. Her photographs were paired with articles about the steel industry in trade magazines. In addition, corporations such as Otis Steel Company hired her directly for its brochures and advertisements.

In 1929, Margaret received the opportunity of a lifetime — she was offered a job as staff photographer for a new magazine, Fortune. It was the first publication in America to focus on big business and feature photography as a central part of its articles. So she moved to New York City and never looked back.

Margaret enjoyed her newfound fame and led an extravagant lifestyle — she even leased space in the new Chrysler Building for her studio. Although she charged a premium for her photographs, she made very little profit. As a result, she was frequently in debt.

Margaret enjoyed her newfound fame and led an extravagant lifestyle — she even leased space in the new Chrysler Building for her studio. Although she charged a premium for her photographs, she made very little profit. As a result, she was frequently in debt.

In the 1930s, Margaret was sent to cover the industrialization of both Germany and the Soviet Union. While overseas, she became interested in photographing people as well as machines. Then, Margaret traveled across the nation and recorded human suffering during the Great Depression. And the experience changed her forever.

In 1936, Margaret became one of the first staff photographers for new illustrated news magazine called Life. And one of her photographs was featured on the cover of the first issue. Margaret’s photographs helped to make Life an instant success. And her work style became the standard for all other photographers on staff.

Margaret happened to be in Europe on assignment in 1938 when Hitler invaded Czechoslovakia. So she extended her stay to cover the beginning of World War II. In fact, she was the only foreign photographer in Moscow when Nazi Germany bombed the city. Then, she became the first woman to be accredited as a war correspondent by the US Army Air Forces in 1942. She was stationed in England at first, but longed to fly on combat missions with the troops.

Margaret as a war correspondent (Time Magazine)

Finally, Margaret’s wish came true when she was allowed to accompany the troops to North Africa. She traveled as part of the convoy on a ship, which was torpedoed by the Germans en route. Once in Algiers, she flew on bombing missions and took as many pictures from the air as possible. The next year, she accompanied the Army on its invasion of Naples. She flew in reconnaissance missions and photographed behind enemy lines, which provided the Army with invaluable intelligence. She also photographed the aftermath of battles, including evacuation of hospitals and wounded soldiers.

After every assignment, the Army sent Margaret home and didn’t want her back. She was a liability — she didn’t follow the rules, she was demanding, and she required more supervision than other war correspondents. But Margaret always figured out how to get back into the action. Somehow, she convinced the Army to allow her to accompany General George Patton’s Third Army as it advanced into Germany in 1945.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Margaret grew up with two siblings in a quiet town in New Jersey, surrounded by books, maps, and nature. Margaret spent a lot of time capturing salamanders and frogs in the marsh behind their house.

Both of Margaret’s parents were the children of immigrants. Her father came from a Jewish family, but was non-practicing and kept his heritage a secret. Margaret and her siblings grew up as Christians. In fact, she didn’t know her father was Jewish until after he died.

Both of Margaret’s parents were the children of immigrants. Her father came from a Jewish family, but was non-practicing and kept his heritage a secret. Margaret and her siblings grew up as Christians. In fact, she didn’t know her father was Jewish until after he died.

Margaret’s father was an inventor and engineer who worked at a printing press factory, with over 25 patents to his name. He was a quiet man but had a big influence on Margaret’s life. He introduced her to the world of machines. He also exposed her to the new field of photography, which was his hobby. He was intrigued with the technical aspects — the optics and lenses, as well as the chemical process of developing the film.

Margaret graduated high school in 1921 and enrolled at Columbia University. Her father died from a stroke in 1922, when she was a freshman in college. Devastated, she took up his hobby of photography to feel closer to him and keep his memory alive. While at Columbia, she took a one week course at the Clarence H White School of Modern Photography. And she was hooked.

International Photography Hall of Fame and Museum

Margaret transferred many times throughout her seven-year college career — Columbia University, University of Michigan, Purdue University, Case Western University, and Cornell University. She also experimented with a few different majors, including herpetology and biology. She finally graduated from Cornell with a Bachelor of Arts in 1927.

The one constant during Margaret’s college years was her love of photography. During the summers, Margaret was a counselor and photography teacher at summer camp. She also sold her photographs as postcards for campers to send home. While at Michigan and Cornell, she was a photographer for the school newspapers and sold her photographs on the side. During her senior year, Margaret focused on details of buildings on the Cornell campus — her photographs were a hit with the architecture students and alumni alike.

By the time Margaret graduated from Cornell, she had an impressive start on her photography portfolio. She moved to Cleveland after graduation, which was booming with new factories, machines, and industry. And she wanted to document it all.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- Margaret was born in the Bronx, New York in 1904. She grew up in New Jersey with two siblings (sister, Ruth, and brother, Roger).

- Margaret was half-Jewish but grew up as a Christian. Her father kept his Jewish heritage a secret. Margaret kept the secret as well, which weighed on her through the years.

- Margaret married Everrett Chapman in Ann Arbor when she was 20 years old, who was a fellow photographer and Michigan student. It was a tumultuous marriage and they separated a few years later. Then, she married the novelist, Erskine Caldwell, in 1939. They divorced in 1942.

- Margaret made a career out of documenting the new age of machines and industry with her camera. She was a pioneer of industrial photography and specialized in the steel manufacturing factories in Cleveland.

- In 1930, she became the first photographer (man or woman) for Fortune magazine. Then, she worked for the new magazine, Life, in 1936.

- From 1930-1960, Margaret traveled throughout the world to document major historical events — World War II, the disintegration of the British Empire, the birth of a new nation in India, the harsh conditions of diamond mines in South Africa, and the Korean War.

- Over her career, Margaret received honorary degrees from University of Michigan and Rutgers University and published 11 books.

- In 1953, Margaret started to notice some difficulties with her hands — it was harder to write and operate her cameras. So she went to see a neurologist and was diagnosed with early stage Parkinson’s Disease. At first, she refused to tell anyone about her diagnosis and continued to work. As she declined, however, she underwent two experimental surgeries.

- In 1971, Margaret died at 67 years old from Parkinson’s Disease.

Want to Know More?

American Witnesses and the Third Reich: Photograph of Margaret Bourke-White at Buchenwald (https://perspectives.ushmm.org/item/photograph-of-margaret-bourke-white-at-buchenwald)

International Photography Hall of Fame Museum (https://iphf.org/inductees/margaret-bourke/)

International Center of Photography (https://www.icp.org/browse/archive/constituents/margaret-bourke-white?all/all/all/all/0)

National Women’s Hall of Fame (https://www.womenofthehall.org/inductee/margaret-bourkewhite/)

Bourke-White, Margaret. Portrait of Myself. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1963.

Bourke-White, Margaret. Dear Fatherland, Rest Quietly: A Report on the Collapse of Hitler’s “Thousand Years.” 1946 (reprinted in 2018 by Arcole Publishing).

Goldberg, Vickie. Margaret Bourke-White, a biography. New York: Harper & Row, 1986.