Brilliant Businesswoman

She was born on the estate where her mother had been enslaved and grew up in segregated Richmond as part of the first generation of African Americans born into freedom. She learned quickly that there could be no true freedom without economic independence and became the first woman to charter a bank, while also founding a newspaper and opening a general store. Transport yourself to the 1903 opening celebration for the community changing St. Luke Penny Savings Bank…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

Maggie Lena Walker stood on the corner of St. James and West Baker Street in Richmond, Virginia. She had a perfect view of the opening day celebration at the new St. Luke Penny Savings Bank. The music and speeches were joyful and the air was charged with excitement.

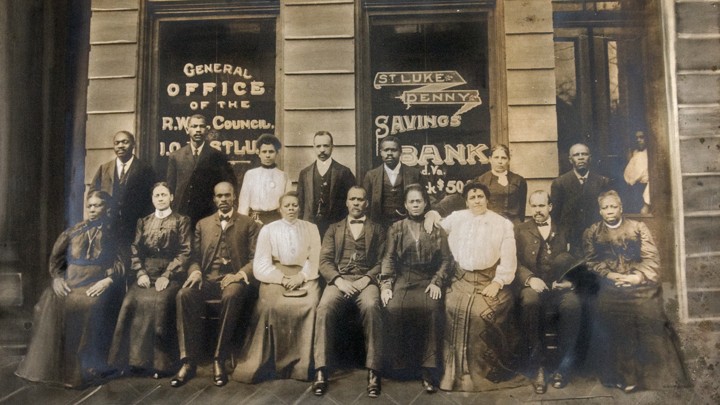

The St. Luke’s Penny Savings Bank staff. Maggie is seated front row, 3rd from right (National Park Service)

The long line of Richmond’s black residents, waiting patiently for the chance to open a bank account, was something to celebrate. It was November 2, 1903, only 38 years since the Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery in the United States, and Richmond had become a hub of society for newly freed families. Maggie’s mom had been a slave and Maggie was born just as the Civil War ended.

The new bank was an important step toward meaningful freedom. White owned banks didn’t welcome black customers, and when they did, they treated them badly. The banks paid them less interest on their deposits and charged them higher interest on loans, if they would even do business with them at all. This made buying a home, starting a business, or saving for an emergency very difficult for black families.

Maggie wasn’t at the celebration as an invited guest or a potential customer. She was there because the bank was her idea, and she was now the first woman in the United States to charter a bank and become its President. Maggie had been the head of the International Order of St. Luke’s, an African American mutual benefit society for four years. A bank was the centerpiece of St. Luke’s plan to build economic power so the black community could become “independent, mobilized, and self-sustaining”enough to demand equal treatment. The bank’s slogan was “Bring It All Back Home.”

Maggie wasn’t at the celebration as an invited guest or a potential customer. She was there because the bank was her idea, and she was now the first woman in the United States to charter a bank and become its President. Maggie had been the head of the International Order of St. Luke’s, an African American mutual benefit society for four years. A bank was the centerpiece of St. Luke’s plan to build economic power so the black community could become “independent, mobilized, and self-sustaining”enough to demand equal treatment. The bank’s slogan was “Bring It All Back Home.”

Nobody in line was turned away. When they got to the teller desk, they were welcomed by black tellers, which was revolutionary in itself, as it was difficult for the black community to find professional employment. One customer opened an account with only 31 cents. At the end of the day, the bank had 280 accounts, over $8000 in deposits, and had sold over $1000 in stock to investors. It was the first of many successful days. By 1913, the bank had more than $300,000 in assets, and by 1920 it had helped 600 families buy a home.

The Power of the Wand

Maggie’s combination of financial skill and community service lives on today in brilliant businesswomen like Mikalia Ulmer. At 14 years old, Mikalia is the CEO of Me & The Bees Lemonade. Mikalia has been making and selling her grandma’s flaxseed lemonade since she was 4 years old and entered a local children’s business competition in her hometown of Austin, Texas.

When she was 10, she pitched her company on Shark Tank and got a $60,000 investment. Her lemonade is sold at Whole Foods and Macy’s. She donates a percentage of her profits to organizations working to save the honeybees. Mikalia, like Maggie, understands the importance of using your power to lift others: “when you have a big voice, make sure that you give others a voice behind you, and that you’re not only growing yourself but helping others grow and giving your expertise to others.”

Her Yellow Brick Road

St. Luke’s was founded in Baltimore just after the Civil War as a way for black citizens to join together to protect themselves from poverty caused by illness or death. Traditional insurance companies didn’t want to do business with black customers, so St. Luke’s filled the gap. Each member contributed money that was pooled and then distributed according to need. The organization spread to communities across Maryland and Virginia.

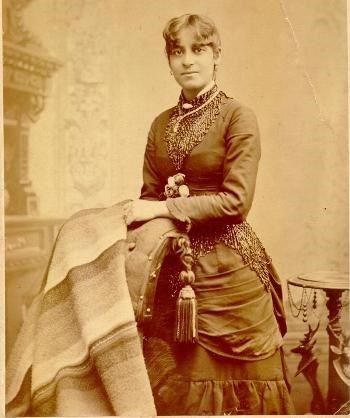

Maggie (National Park Service)

The various St. Luke’s communities sent delegates to a convention every two years to elect its central leaders. Maggie was a delegate before she decided to run for office herself. She used her new power to establish a St. Luke’s Juvenile Branch for teenagers. Maggie believed that teen optimism and spirit led to social change, but that lack of confidence and opportunity for community action kept them on the sidelines.

When St. Luke’s got into financial trouble in 1899, it turned to Maggie for help and elected her to its top leadership role. Her talent for finance and community building saved the day. Her smart investments in real estate and stocks built up a financial cushion and her recruitment efforts increased membership significantly.

Maggie wanted St. Luke’s to be a springboard for greater equality. At the 1901 annual convention, she gave a speech that convinced her audience, among them the first generation of black Americans born into freedom, that they could prosper even though they were often barred from the social and economic life that white citizens took for granted.

Maggie wanted St. Luke’s to be a springboard for greater equality. At the 1901 annual convention, she gave a speech that convinced her audience, among them the first generation of black Americans born into freedom, that they could prosper even though they were often barred from the social and economic life that white citizens took for granted.

Maggie laid out a three part plan. First, St. Luke would start a newspaper to promote and amplify the voice of the black community. Second, St. Luke’s would open a bank to pool, preserve, and grow wealth. Third, St. Luke would open its own department store to keep money in the community. Her soaring words inspired her listeners to action.

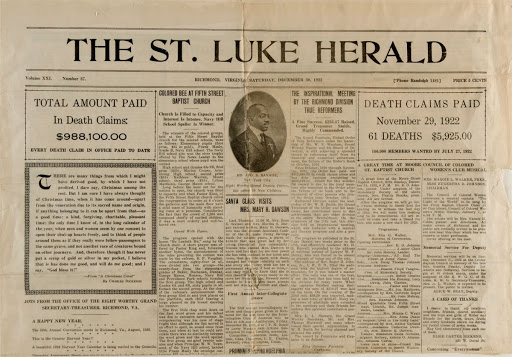

Front page of the St. Luke Herald (National Park Service)

The newspaper, the St. Luke Herald, hit the presses in 1902. It quickly became a trusted source of news about St. Luke’s programs and plans. The paper played a big role in building popular support and excitement for the bank. The Herald had a section for children where they could send questions to Maggie, who they affectionately called “the St. Luke Grandmother.” The bank later would hand out cardboard banks for children to save their spare change, encouraging them to start saving for their dreams early.

Maggie also worked within St. Luke’s to gain support from the leaders of each individual council, asking each one to commit to running all of its financial business through the bank. St. Luke’s leadership team was the bank’s first board of directors, and on August 21, 1903, they appointed Maggie president.

She spent the next few months observing the banking operations of a prominent white-owned bank to get ready to open. She also recruited the head teller at the first black owned bank in the country, Emmett Burke, to work at St. Luke’s instead.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Maggie was born near the end of the Civil War in Richmond, Virginia. Her mother, Elizabeth Draper, was a former slave who was working in the kitchens at Church Hill, a mansion owned by Civil War spy Elizabeth Van Lew. Her biological father, Eccles Cuthbert, was an Irish-American newspaper reporter who was reporting on the Civil War. Maggie was raised by her mother and stepfather, William Mitchell, who was the butler at Church Hill.

The Mitchell family had a taste of financial good fortune when William got a job as the head waiter at the fancy St. Charles Hotel in Richmond. The family, which now included Maggie’s little brother Johnnie, was able to move out of Church Hill into their own home. But when William died suddenly when Maggie was 11 and Johnnie was only 5, they had no savings and no life insurance.

The Mitchell family had a taste of financial good fortune when William got a job as the head waiter at the fancy St. Charles Hotel in Richmond. The family, which now included Maggie’s little brother Johnnie, was able to move out of Church Hill into their own home. But when William died suddenly when Maggie was 11 and Johnnie was only 5, they had no savings and no life insurance.

Elizabeth had to figure out how to keep the family afloat. She knew that there was plenty of work for white families who no longer had slave labor to do their household chores. Elizabeth started a laundry service business, and she soon had a long list of clients. Maggie was one of her mom’s most valuable employees — she made the rounds of customers’ homes collecting dirty clothes and returning clean clothes. She spent years at the servant’s doors of these households seeing how the white families of Richmond lived.

Maggie attended school when she wasn’t working, as Richmond was fairly progressive for the south, and had established public schools for black children. When Maggie was 14, her mom, Sunday School teacher, and pastor all encouraged her to join St. Luke’s and participate in its public service and community building projects.

Young Maggie (National Park Service)

When she was 17, Maggie organized a student strike protesting the inequality of white and black graduation ceremonies. Although the principal threatened to cancel their graduation altogether, once the students got local newspaper coverage of their protest, he allowed them to graduate in the high school auditorium. Maggie was at the top of her class.

After graduation, Maggie found a job as a teacher, and took accounting and business classes in her spare time.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- Maggie was born on July 15, 1864 in Richmond, Virginia.

- When Maggie married Armistead Walker at age 22 she had to quit her job because married women were not allowed to work as teachers.

- Maggie helped organize the 1904 boycott of the Virginia Passenger and Power Company after the company decided to enforce segregated seating on its streetcars. The streetcar conductors were allowed to make black passengers move so white passengers wouldn’t have to sit near them. Maggie encouraged Richmond’s black residents to “preserve their dignity by walking.” The VPPC went out of business within a year.

- The St. Luke Emporium opened in April 1905 and carried goods that black consumers needed. Unlike white owned stores, the Emporium didn’t charge black customers more than white ones and allowed black customers to try on clothes. It also provided desirable jobs for black women.

- The Emporium closed in 1911 after surviving years of white shopkeepers working to shut it down. They first offered St. Luke’s $10,000 to not open the store. Then, they filed numerous legal complaints, resulting in constant inspections. Finally, they told manufacturers and farmers that if they supplied goods to the Emporium they couldn’t supply the white stores, which was business they couldn’t afford to lose.

- Maggie started the first Girl Scout troop for black girls in the south in 1932.

- Maggie received an honorary degree from Virginia Union University, a historically black college in Richmond.

- Maggie cofounded the Richmond Chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the Richmond Council of Colored Women.

- Maggie’s leadership prevented the bank from failing after the 1929 Stock Market Crash. She oversaw a merger with two other Richmond black owned banks and became chairman of the Board of Directors of the new Consolidated Bank and Trust Company. Until 2005, it was the oldest continually African-American operated bank in the United States.

- Maggie and her family lived in Jackson Ward, in Richmond, which was known as the “Harlem of the South.” The National Park Service bought the Walker home in 1979 and opened it to the public.

- Maggie died on December 15, 1934.

- There is a college prep school in Virginia named the Maggie L. Walker Governor’s School for Government and International Studies.

- In 2017, the city of Richmond put up a 10 foot bronze statue of Maggie in its town center. Maggie is holding a checkbook on one hand as a symbol of the bank that gave her community hope and power.

Want to Know More?

Branch, Muriel Miller. “Walker, Maggie L.” American National Biography.

Mayo, Tony. “Black Business Leaders Series: A Remarkable Legacy of Firsts, Maggie Lena Walker.” Working Knowledge, 16 Feb. 2017 (Harvard Business School Podcast).

Schiele, Jerome H., Jackson, M. Sebrena, and Fairfax, Colita Nichols. “Maggie Lena Walker and African American Community Development.” Affilia, Spring 2005.

“Maggie Lena Walker and the Independent Order of St. Luke.” Encyclopedia Virginia.

“Maggie L. Walker,” “Maggie Walker National Historic Site,” “The St. Luke Penny Savings Bank.”National Park Service.