Brilliant Businesswoman

She grew up in a segregated town with a dentist father whose skills overcame the prejudices of his white patients, and who believed that business ownership was a way to build generational wealth in spite of discrimination. But her dad died young, and she dropped out of college to help her mother with finances. Years later, her own husband died young – soon after purchasing a struggling ice cream company. Although a Black woman in the dairy industry was unprecedented and white customers buying a Black product was considered “impossible”, she decided to run the business herself. Travel back in time to 1971, savor a taste of Baldwin’s gourmet ice cream, and meet Jolyn Robichaux…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

Jolyn Robichaux still couldn’t believe her husband Joe was gone. Joe had been a force of nature, which made it even more shocking when he was diagnosed with a leukemia that ravaged his body with alarming speed. He died in 1971, just 10 days after he was diagnosed.

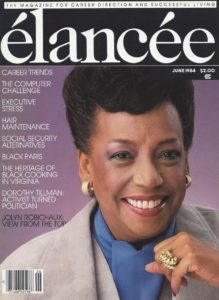

Jolyn with her signature style – business professional with flair (Chief Writing Wolf)

Suddenly, Jolyn was a 43 year old single mother deciding what to do with the business Joe had purchased four years earlier – Baldwin Ice Cream Company, a South Side of Chicago institution. When Joe bought Baldwin, he was an executive at a milk company and Jolyn was home raising their two kids. Jolyn agreed to work at Baldwin at the company as a secretary while the kids were in school. While she was Joe’s eyes and ears, he stopped in each afternoon to make the executive decisions.

With Joe gone, Baldwin needed a new leader. She and Joe had purchased Baldwin, a historic Black owned brand, to be a legacy for their children. Jolyn considered hiring someone. Their daughter Shelia reminded her that “Daddy wanted this company to be a family business” and offered to take on more of the household chores if Jolyn took charge at Baldwin. Jolyn’s own dad had always told her that business ownership was the most effective way to build family wealth. With all that in mind, Jolyn decided to “just do it herself.”

Jolyn expected to have more challenges to her leadership than Joe had. He was a big guy with a deep voice who commanded respect. Jolyn was about to be the only Black woman in the ice cream industry and needed a strategy for cultivating that same respect from her employees, suppliers, and competitors. She decided to combine her knowledge of modern business procedures, a carefully curated professional wardrobe and style, and her skill at conversation and building personal relationships.

Black women were a rarity in executive offices. When Jolyn walked into meetings, she could feel many eyes on her wondering how to react to “this oddity” – as she described herself. But once she showed how capable she was, Baldwin employees were happy to follow where she led. Some of her first accomplishments were upgrading the accounting system and improving delivery by providing drivers with new uniforms and performance incentives.

When negotiating deals with Baldwin’s wholesalers and suppliers, they required that she bring along another Black woman to the meeting. Men didn’t want to risk being in public with her alone and having people assume they were a romantic couple. But being a woman in a male dominated industry did provide some advantages. Her colleagues and competitors were willing to talk more freely and share more information with her that they did with other men. And once she realized her presence made them more cooperative instead of competitive, she moved to expand Baldwin’s executive ranks to more woman. Her first hires were family – her sister was vice president, her mom managed the finance department, and her niece worked in sales as a manager and account executive.

Chicago’s own Baldwin ice cream breaks the freezer barrier

Jolyn’s biggest challenge at Baldwin was devising a strategy to expand its market. When she took over, Baldwin was sold in 8 ice cream parlors and some mom & pop grocery stores in the Black neighborhoods of Chicago’s South Side. And as Chicago became less segregated and people moved to other areas, sales suffered. Jolyn needed “break the freezer barrier” – industry lingo for getting your ice cream into the freezers of large grocery stores.

Jolyn got to work convincing wholesale buyers to purchase Baldwin’s. It was a tough sell at first – most laughed at the idea of selling “Black products” to a general audience. They said it was impossible. Jolyn persisted, telling wholesalers and grocers that “our ice cream sells itself once you put it in the freezers.” And she was right – when Baldwin’s became available in Chicago supermarkets, people tasted it and were hooked.

The Power of the Wand

Jolyn made her mark on the business world

Jolyn ran Baldwin Ice Cream Company for 20 years. It was the only Black owned ice cream producer in the United States. When she started, sales were $300,000/year. By 1985, sales were $5,000,000/year!

Baldwin’s became a Chicago institution but Jolyn wanted to extend its reach beyond Illinois. She secured a Baldwin’s ice cream parlor at Chicago O’Hare airport in 1983, so visitors could get a taste and then ask their hometown supermarkets to stock it. Within 6 years, major grocery chains were selling it all around the Midwest. Arkansas, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Michigan, Mississippi and Tennessee.

Her Yellow Brick Road

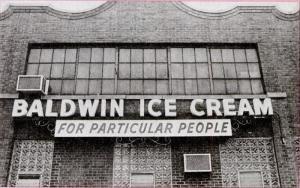

Baldwin Ice Cream factory in Chicago (WTTW)

Chicago leaders segregated the city after the 1919 race riots and zoning limited Black citizens to neighborhoods on the South Side. Baldwin Ice Cream was founded in 1921 under the name Seven Links Ice Cream. There were seven original founders, including Kit Baldwin. All were Black postal workers with entrepreneurial dreams. They opened their first ice cream parlor on a busy corner in the Washington Park. Over the next 20 years, they added six more locations in other South Side neighborhoods.

Baldwin’s ice cream tasted homemade – with high quality flavorful ingredients – and the servings were generous. Word spread quickly and on nice evenings, a line would form around the block. Customers agreed the experience was worth the wait. Each cone was stuffed with as much ice cream as it could hold – there was no standard size. Customers could also order ice cream to go, packed in a one gallon box.

In 1946, Kit bought the business from his partners and renamed it Baldwin Ice Cream. After Kit died in 1967, Jolyn’s husband Joe got a call asking if he was willing to buy it. Investors wanted the company to continue serving its primarily Black customer base with Black ownership, and Joe was one of the only Black men in the Chicago dairy industry. Wanzer Dairy had hired Joe to navigate the politics involved in their planned expansion. Joe was good friends with Mayor Daley, a Democratic ward committeeman, Cook County Jury Commissioner, and a member of the Illinois Athletic Commission.

In 1946, Kit bought the business from his partners and renamed it Baldwin Ice Cream. After Kit died in 1967, Jolyn’s husband Joe got a call asking if he was willing to buy it. Investors wanted the company to continue serving its primarily Black customer base with Black ownership, and Joe was one of the only Black men in the Chicago dairy industry. Wanzer Dairy had hired Joe to navigate the politics involved in their planned expansion. Joe was good friends with Mayor Daley, a Democratic ward committeeman, Cook County Jury Commissioner, and a member of the Illinois Athletic Commission.

When Joe bought Baldwin, he and Jolyn had been married for 15 years and had two kids at home. Jolyn didn’t have any management experience – before marrying Joe, she worked as a court reporter, secretary, and medical assistant. After they married, Jolyn didn’t need to work, but wanted the stimulation. She worked with Joe at a Catholic community center, and helped support the women’s track team he coached. She even spent three months in Africa chaperoning track athletes on a Goodwill Tour.

Jolyn with husband Joe and their children Shelia and Joe Jr. (Chicago Sun-Times)

After Jolyn had their first baby, her in-laws encouraged her to go back to college and offered to help with childcare. Jolyn decided to do it – her dad had died young, which had caused her mom significant financial stress. Jolyn had carried guilt about dropping out of college and wanted a degree to fall back on if anything happened to Joe. She earned a degree in education from Chicago State College in 1960.

She considered teaching but then heard that General Mills was looking for a Black woman to represent Betty Crocker and Gold Medal flour. They were looking to expand their market by hosting baking demonstrations for Black conventions, companies, and community organizations. Jolyn was determined to be the one chosen. She interviewed and then sent General Mills regular letters detailing her continued interest and relevant skills and civic connections. It took three months of campaigning but in the end, she was hired! Jolyn traveled around the country doing baking demonstrations for a few days every two weeks. The pay was generous and the business experience priceless, but it became too difficult to juggle with family so she resigned.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Jolyn Howard grew up in Cairo, a town in southern Illinois just north of the Mason-Dixon line. Cairo was very segregated. Black citizens were not allowed in the schools, library, swimming pool, movie theaters, and restaurants in the white part of town, so created their own economy on their side.

Jolyn’s dad was a skilled dentist. There weren’t many dentists in town, and Dr. Howard had a reputation for pain-free care – he was gentle and his humor worked as a distraction. Even though Cairo was a town where he could have been lynched for accidentally touching a white person on the sidewalk, he treated many white patients. Their need for dental care overcame their prejudice. Even so, Dr. Howard had to enter his own office through the back door while his white patients entered through the front.

Jolyn’s dad was a skilled dentist. There weren’t many dentists in town, and Dr. Howard had a reputation for pain-free care – he was gentle and his humor worked as a distraction. Even though Cairo was a town where he could have been lynched for accidentally touching a white person on the sidewalk, he treated many white patients. Their need for dental care overcame their prejudice. Even so, Dr. Howard had to enter his own office through the back door while his white patients entered through the front.

Dr. Howard had a natural talent for business. During the Great Depression, he traded dental skills to local farmers for food. Later he used his dental profits to buy a hamburger restaurant and a movie theater, explaining Jolyn that business ownership was the path to success and security. Her dad told her she could be anything she wanted to be – not just what girls were expected to be. Her mom was a businesswoman too who operated the only Black beauty salon in Cairo.

Jolyn attended K-8th grade in a one room schoolhouse. She loved to read and was a good student. When she finished her work, she would listen to what the teacher was teaching the grade above her. By high school, she was bored with learning and rebelled by skipping class. When she pushed it too far and was suspended from junior prom, she decided to turn over a new leaf and became class valedictorian.

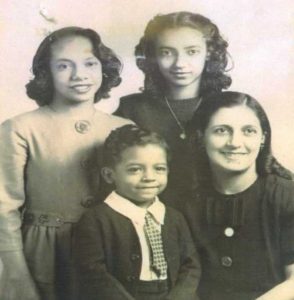

Jolyn with her mom and siblings (Robichaux Family)

Tragedy struck three weeks before her 1945 high school graduation, when her dad was admitted to the hospital for complications from a blood disease. Three days before the ceremony, he died. Jolyn still attended and gave her valedictorian speech, as her father had wanted. His funeral was two days later. Jolyn needed a distraction from her grief and asked her mom if she could spend the summer working in Chicago. Her mom agreed on the condition that Jolyn would still go to college in the fall.

So at age 16, Jolyn boarded the train to Chicago. She initially stayed with family friends in the segregated neighborhoods on the Southside known as the“Black Belt” She found a job dictating letters for the Montgomery Ward catalog and made enough money to move into the Phyllis Wheatley Home for Working Girls right down the street. She kept her promise and left for Fisk University in Nashville, as planned, at summer’s end.

Well-to-do Black families sent their daughters to Fisk with the hopes they would meet and marry one of the men attending the Black medical school across the street. But Jolyn wasn’t looking for a husband, and while she had academic success at Fisk, she worried about the financial strain on her family. Supporting herself during her Chicago summer gave her the confidence to quit after her sophomore year. She moved back to Chicago with a plan to work and attend college at night. She returned to the Phyllis Wheatley home and got a job at Spiegel’s catalog transcribing customer letters. She found it hard to focus on college in between work and her social life, only completed one semester in her first 3 years, and withdrew.

Well-to-do Black families sent their daughters to Fisk with the hopes they would meet and marry one of the men attending the Black medical school across the street. But Jolyn wasn’t looking for a husband, and while she had academic success at Fisk, she worried about the financial strain on her family. Supporting herself during her Chicago summer gave her the confidence to quit after her sophomore year. She moved back to Chicago with a plan to work and attend college at night. She returned to the Phyllis Wheatley home and got a job at Spiegel’s catalog transcribing customer letters. She found it hard to focus on college in between work and her social life, only completed one semester in her first 3 years, and withdrew.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- Jolyn was born in Cairo, Illinois on May 21, 1928.

- Jolyn married Joe Robichaux on June 6, 1952. They had two children: Sheila and Joseph, Jr.

- Jolyn wanted to finish out his jury commissioner term. She put on a black suit and veil and went to a council meeting to make a point to the mayor that she was the best one to carry on Joe’s legacy. He offered her the position the next day.

- In 1985, Jolyn was the first Black woman to be named the U.S. Commerce Department’s National Minority Entrepreneur of the Year.

- Jolyn’s biggest business disappointment was the commercial failure of her favorite ice cream flavor: brandy black eyed pea.

- Jolyn sold Baldwin Ice Cream in 1992. Today, it is part of Baldwin Richardson Foods Company, and produces dessert fillings and toppings.

- After Jolyn sold Baldwin, she moved to France. She traveled Europe and started a business that booked American gospel singers for concerts at the American Cathedral in Paris.

- Eventually, Jolyn moved to Texas to be near her children and their families. She became a valued community member, serving on the Heart Disease Research Project at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and the Dallas Opera Board of Directors. She also filled in as a substitute teacher in the Dallas schools.

- Jolyn died on March 9, 2017. She was 88.

Want to Know More?

Hodge, Adele. “Interview with Jolyn H. Robichaux” (The History Makers Feb. 24, 2003).

Williams, Ricardo. An Unlikely CEO: The Jolyn Robichaux Story (Ricardo Williams 2019).

Gottesman, Andrew. “One for the Books” (Chicago Tribune Sept. 22, 1991).

Gunderson, Erica. “Ask Geoffrey: 2/11” (WTTW Feb. 11, 2015).

Hautzinger, Daniel “The Black and Woman Led Success of a Chicago Ice Cream Company.” (WTTW Feb. 7, 2019)

Kim, Rachel. “Breaking the Freezer Barrier” (South Side Weekly May 2, 2017).

O’Donnell, Maureen. “Jolyn Robichaux, Built Chicago’s Baldwin Ice Cream, Dead at 88” (Chicago Sun Times May 9, 2017).