Brilliant Businesswoman

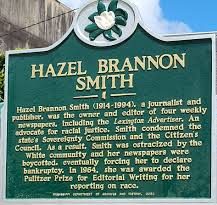

While growing up in the Jim Crow South, she didn’t question the segregation that was all around her and didn’t see the discrimination that African Americans lived with every day. She graduated from college with a degree in journalism and then bought her own community newspaper in Mississippi. While she covered the events around her, her eyes were opened to the racism and discrimination that surrounded her. She spoke out against it in her newspaper, despite being ostracized by her community and threatened by the KKK. Roll back to 1964 and meet Hazel Brannon Smith …

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

Hazel Brannon Smith was typing up an article for her newspaper at home when the phone rang. It was the afternoon of May 4, 1964, and a friend from New York City congratulated her on winning the Pulitzer Prize. Hazel had no idea what he was talking about and asked him if it was a joke. Her friend proceeded to read the announcement from Columbia University out loud to her over the phone. She hung up, stunned. It wasn’t a joke. She indeed was the 1964 recipient of the Pulitzer Prize for editorial journalism. And the first woman in history to win the award in that category.

In granting the award, the Pulitzer committee acknowledged her “steadfast adherence to her editorial duties in the face of great pressure and opposition” in all of her work. Hazel owned and operated four community newspapers in Mississippi and used her editorial voice to support the Civil Rights Movement. She condemned the violence and intimidation against Black citizens, as well as the lack of accountability for white citizens who broke the law. She also spoke out against segregation and in favor of the landmark decision, Brown v. Board of Education.

Hazel received the Pulitzer Prize right before Freedom Summer took place in Mississippi. She supported the efforts highlighted the events in her newspapers — voter registration, freedom schools, and community centers with resources for African Americans. Hazel also featured some of the 50 people who volunteered throughout the state and condemned the murders of three such volunteers. Finally, she welcomed civil rights leaders into her home, including Martin Luther King, Jr.

Hazel received the Pulitzer Prize right before Freedom Summer took place in Mississippi. She supported the efforts highlighted the events in her newspapers — voter registration, freedom schools, and community centers with resources for African Americans. Hazel also featured some of the 50 people who volunteered throughout the state and condemned the murders of three such volunteers. Finally, she welcomed civil rights leaders into her home, including Martin Luther King, Jr.

Over the years, Hazel suffered greatly for her support of the Civil Rights Movement. She was shunned by the community and ostracized from her social circles. Her husband was fired from his job as administrator of the local hospital. The local KKK burned a cross in her front yard. She was harassed and threatened on a regular basis, and the victim of numerous smear campaigns. Her Lexington newspaper office was set on fire. Her Jackson office shattered by dynamite. The KKK discussed hiring a hit man to “eliminate” her. The communities boycotted her newspapers. Employees quit and she had to do the work of 3 people. Advertising revenue and paper sales dried up. Copies of her newspapers were stolen. She and her husband faced financial ruin. She had to apply for grants from around the country to keep her business going. But she never backed down.

Hazel didn’t always have such liberal views. In fact, she had supported segregation for most of her life. She didn’t question how she had grown up. She believed that everyone, black and white alike, preferred to live separately. And she thought that separate could really be equal — it was just a matter of resources.

Hazel didn’t always have such liberal views. In fact, she had supported segregation for most of her life. She didn’t question how she had grown up. She believed that everyone, black and white alike, preferred to live separately. And she thought that separate could really be equal — it was just a matter of resources.

But then Hazel experienced the inequities firsthand. Her employee, a Black man, was shot in the leg by the county sheriff. The reason — he was on the street after dark and disturbing the peace by “whooping” loudly. He showed up at her newspaper office, traumatized and bleeding. She tried to get assistance, but no one would help a Black man. Hazel was outraged and published an editorial in her newspaper. She condemned the violence, demanded justice, and called on the sheriff to resign. Eventually, the sheriff sued her for libel and a jury of all white men found her guilty. However, Hazel appealed to the Mississippi Supreme Court and won on November 7, 1955.

After witnessing her employee’s treatment, Hazel started to listen and ask questions. She learned about the intimidation and violence, the disparities between education for white and black children; the poll taxes and other efforts to prevent voter registration. She was appalled at the routine violation of constitutional rights experienced by Black citizens. And she wrote about it in her newspapers.

The Power of the Wand

Hazel Brannon Smith was one of the only women to own a newspaper in the Jim Crow South. Further, she was one of the only editors who broke from the views of white Southerners and objected to the racism and discrimination towards African Americans in her community. She was an example of independent journalism, even though it was unwanted in her community and despite the personal consequences to her. Her legacy has been celebrated by many independent journalists ever since.

Her Yellow Brick Road

Shortly after Hazel graduated from college, she learned from a classmate that the weekly newspaper, the Durant News, was for sale. Durant was a town of about 2,500 people that was located in Holmes County, Mississippi — one of the top cotton producers in the state.

Hazel Brannon Smith (Mississippi State University Special Collections)

In 1936, journalism was a man’s world. But Hazel wanted to own a newspaper. So she obtained a bank loan for $3,000 and bought the Durant News. She was only only 22 years old. And had never set foot in Mississippi.

Hazel became the owner, publisher, and editor of the Durant News. And she threw herself into the job — she lived and breathed the news of Holmes County. She wrote all the editorials and sold advertisements, mocked all the pages, and supervised a staff of four employees. Before long, the newspaper became profitable.

In 1943, Hazel bought a second newspaper in Lexington, Mississippi (the county seat of Holmes County). The Lexington Advertiser was a bigger newspaper, with a readership of 1,800 subscribers. Its owner was called into active duty with the US Navy during World War II and offered Hazel a chance to buy the newspaper. She eventually purchased two additional newspapers, both in Mississippi.

Hazel’s newspapers were a financial success in the early years. At first, she ran her newspapers similar to others in the South — she had separate pages in the newspaper for news pertaining to the white and Black communities and she listed announcements into separate columns. At first, she seemed oblivious to the tension between whites and blacks in the communities covered by her newspapers. And she embraced segregation as the natural way of life in the South.

Hazel’s newspapers were a financial success in the early years. At first, she ran her newspapers similar to others in the South — she had separate pages in the newspaper for news pertaining to the white and Black communities and she listed announcements into separate columns. At first, she seemed oblivious to the tension between whites and blacks in the communities covered by her newspapers. And she embraced segregation as the natural way of life in the South.

It didn’t take Hazel long, however, to exercise some journalistic independence. In 1943, she featured a story on the front page of the Durant News about an African American civic group in Durant that donated money to the local Red Cross. Then, she landed an exclusive interview with Eleanor Roosevelt — Hazel admired her but most Southern white women in the community disliked Eleanor Roosevelt and her policies. Hazel wasn’t afraid to make waves by criticizing the police and courts for overlooking illegal activity such as bootlegging and gambling.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Hazel was born in 1914 in the Jim Crow South. She grew up with four siblings in Alabama. Her dad was an electrician and her mom was active in the Southern Baptist Church. Her parents raised her to love everybody and respect and consider the rights of others. However, her family didn’t question the “Southern way of life” and accepted the segregation that permeated the community.

While they supported segregation, the Brannons also displayed civility in their personal dealings with African Americans. Her father broke with custom by greeting his Black customers at the front door of his shop. Her mother volunteered at Black churches regularly as part of her Missionary Society work. And they treated their Black maid as part of the family. It was unusual for the time and place in history.

While they supported segregation, the Brannons also displayed civility in their personal dealings with African Americans. Her father broke with custom by greeting his Black customers at the front door of his shop. Her mother volunteered at Black churches regularly as part of her Missionary Society work. And they treated their Black maid as part of the family. It was unusual for the time and place in history.

While in high school, Hazel was editor of the yearbook, participated in student government, and was a member of the French, Glee, Drama and Audubon clubs. She graduated at age 16, but her parents were concerned that she was too young to attend college. So Hazel went to work for the Etowah Observer, a weekly newspaper in her home county. She earned $1 per column that was published. She reported news, sold advertising, and kept the books. Before long, she decided that she wanted to own a newspaper.

In 1932, Hazel attended the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa. She became the managing editor of the campus newspaper, the Crimson White, and worked on the staff of the yearbook. She also joined a lot of clubs — glee club, quill club, joined a sorority (Delta Zeta), Women’s Athletic Association, YWCA. Hazel graduated in three years by taking classes every summer. In 1935, she received a BA in journalism and minor in political science.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- Hazel Freeman Brannon was born on February 5, 1914, in Alabama City as the oldest of five children.

- Hazel graduated from Gadsden High School in 1930, at age 16. She attended University of Alabama and graduated in 1935.

- In 1949, at age 35, Hazel met Walter Dyer Smith, a ship’s purser known as Smitty, on an around-the-world cruise. The couple married on March 12, 1950 at the First Baptist Church in Durant. He had a graduate degree in audio visual education and took many of her pictures while she was reporting on events abroad.

- Before being ostracized, Hazel was a leader in the Durant and Lexington communities, serving on both Chamber of Commerces, Professional Women’s Club and honorary member of the Rotary clubs (which was all men).

- Hazel was involved in politics her entire adult life. She served as delegate to Democratic National Convention. She appeared regularly on the Today Show to explain state politics. She ran for state senate in 1967 and 1971, but lost both times.

- In 1994, ABC-TV broadcast an unauthorized, fictionalized movie of Hazel’s life, A Passion for Justice: The Hazel Brannon Smith Story.

- Hazel was inducted into the Communication Hall of Fame at the University of Alabama and the Mississippi Press Association Hall of Fame.

- Hazel received numerous awards, including: Fannie Lou Hamer Humanitarian Award; Elijah Parish Lovejoy Award for Courage in Journalism; Headliner Award; Golden Quill Editorial Award; Woman of Conscience Award; Abraham Lincoln Award from the National Educational Association, and Woman of Achievement Award from the National Federation of Press Women.

- Hazel’s nickname was “Great Lady of the Press.”

- In 1980, Hazel went into debt to build her dream house, which was modeled on the plantation home in Gone wit the Wind. The bank foreclosed on her home and property in 1985.

- Hazel began to exhibit early signs of Alzheimer’s shortly after husband died in 1982. She died on May 15, 1994 from Alzheimer’s Disease and liver cancer at a nursing home in Tennessee.

Want to Know More?

Davies, David R., ed. The Press and Race: Mississippi Journalists Confront the Movement. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2001.

Roberts, Gene, and Hank Klibanoff. The Race Beat: The Press, The Civil Rights Struggle, and the Awakening of a Nation. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2007.

Smith, Leonard. Hazel Brannon Smith: ‘A Product of her Times’ — and a Force for Chance.” The Pulitzer Prizes (https://www.pulitzer.org/article/hazel-brannon-smith-product-her-times-and-force-change).

Whalen, John A. Maverick Among The Magnolias: The Hazel Brannon Smith Story. Philadelphia: Xlibris, 2000.

A Passion for Justice: The Hazel Brannon Story. Directed by James Keach, 1994.