Amazing Artist

She grew up in the South Side of Chicago and experienced discrimination on a daily basis. She found refuge in the power of words and found joy in writing poetry. She was 13 years old when her first poem was published. Over the years, her poetry focused on documenting the lives of Black families who lived in her neighborhood, including their hopes, dreams, and struggles. Her work resonated with a lot of people, including those on the selection committee for the Pulitzer Prize. Step back to 1950 and meet Gwendolyn Brooks…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

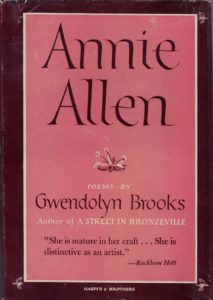

Gwendolyn Brooks answered the telephone and heard the news of a lifetime. A reporter from the Chicago Sun-Times told her that she won the 1950 Pulitzer Prize for her book of poetry, Annie Allen. She was completely shocked to be the first African American to win the coveted Pulitzer Prize.

Gwendolyn sat in the dark to take it all in. It wasn’t by choice, however — her electricity had been turned off because they couldn’t afford to pay the bill. She took her young son to the movies to celebrate, but had a hard time focusing on the movie. She was completely thrilled by the honor, but worried about the attention. She knew reporters and photographers would come to her home and might need electricity. It would be embarrassing if they plugged in their equipment and nothing happened.

Gwendolyn Brooks, Illinois State Library

The next day, reporters and photographers arrived at Gwendolyn’s house and wanted to interview her. She managed to give most interviews during the day. But then, reporters from the Chicago Tribune arrived at dusk. She showed them into the living room and held her breath when they plugged in their equipment. To her surprise and relief, the lights came on. Someone had paid her electricity bill.

After being awarded the Putlizer Prize, Gwendolyn received a number of job opportunities to teach poetry. She accepted, in part because they needed the money. But she also accepted because she loved to share the joy of poetry and help people express themselves through the written word. Her first position was teaching a poetry workshop at Columbia College, a communication arts school in Chicago. Her main goal was to make poetry accessible, so she played music and recordings of modern poets.

The award for the Pulitzer Prize was $500. Despite her poverty, Gwendolyn used all her award money to encourage children to nurture their writing skills and help people trying to make a career in writing. She hosted young artists in their home, helped aspiring poets with expenses such as rent and utilities, and sponsored poetry competitions in schools on the South Side of Chicago.

The award for the Pulitzer Prize was $500. Despite her poverty, Gwendolyn used all her award money to encourage children to nurture their writing skills and help people trying to make a career in writing. She hosted young artists in their home, helped aspiring poets with expenses such as rent and utilities, and sponsored poetry competitions in schools on the South Side of Chicago.

Gwendolyn’s career took a turn in 1967, when she attended the Second Black Writers’ Conference at Fisk University. She was inspired by the energy and ideas of the college students and embraced the opportunity to become a leader in the new Black Arts Movement. She focused on the development of Black literature and nurtured Black artists. She also left her publisher, Harper & Row, to work with smaller Black publishing houses.

In 1968, Gwendolyn was named Poet Laureate for the state of Illinois. In that role, she traveled to communities, large and small, across the state. She visited facilities such as schools, colleges, universities, prisons, hospitals, and drug rehabilitation centers. She read her work to various audiences and encouraged people, old and young, to express themselves through poetry. She also organized poetry activities in under-served areas of Chicago. Gwendolyn served as Poet Laureate for the state of Illinois until her death in 2000.

The Power of the Wand

Gwendolyn Brooks was a pioneer in American literature — one of the most widely-read poets of the 20th century, an influential leader in both the Black Arts Movement and the feminist movement, a fierce advocate of disadvantaged communities and students, and the first Black author to win a Pulitzer Prize. And her work has inspired new generations of Black artists, including Amanda Gorman (America’s first National Youth Poet Laureate).

Her Yellow Brick Road

After graduating from college, Gwendolyn took a job as a secretary for a local pastor. For 4 months, she answered letters, collected money and delivered potions and charms. However, when the pastor asked her to become his assistant and join his church, she quit the job. Then, she joined the NAACP Youth Council in Chicago, and eventually became its publicity director. She was impressed with the work her colleagues were doing and felt accepted for the first time.

Despite her various jobs, Gwendolyn never stopped writing poetry. She participated in poetry workshops and classes at the Southside Community Art Center. She was also mentored by a number of prominent members of the Harlem Renaissance, who all pushed her to develop as a writer and improve her technique.

Gwendolyn experimented with a wide range of poetry. She perfected traditional forms of verse such as sonnets, ballads, and odes. She also experimented with a variety of meter, stanza and rhyming techniques. As her career progressed, she embraced more contemporary forms of poetry such a free verse and dramatic writing. She even wrote a novel.

In her work, Gwendolyn incorporated her experiences growing up in the south side of Chicago, as well as her observation of others. Her favorite topic was the everyday life she witnessed around her — on the street, from her apartment window, and from conversations with neighbors. She documented the lives of Black families, including their hopes, dreams, and struggles.

In 1943, Gwendolyn read in a local newspaper that the Midwestern Writers Conference was hosting a poetry contest. On a whim, she decided to enter one of her poems. To her surprise, it won first prize! This success opened doors and encouraged her to continue pursuing her dream. She went on to win the first prize in 1944 and 1945 as well. At the award ceremony in 1945, the audience was shocked when her came was called and she stepped up to the stage — on one expected to see a Black woman receive the award.

In 1943, Gwendolyn read in a local newspaper that the Midwestern Writers Conference was hosting a poetry contest. On a whim, she decided to enter one of her poems. To her surprise, it won first prize! This success opened doors and encouraged her to continue pursuing her dream. She went on to win the first prize in 1944 and 1945 as well. At the award ceremony in 1945, the audience was shocked when her came was called and she stepped up to the stage — on one expected to see a Black woman receive the award.

Gwendolyn decided her next step was to look for a publisher. So she sent a manuscript of her poems to Harper & Brothers (later Harper Collins), which liked her work but suggested that she expand it to a book-length collection of poems. Gwendolyn blocked out everything else and got to work. — she wrote 11 sonnets in just a few months. The result was her first book of poetry, A Street in Bronzeville, which was published in 1945. The collection of poems focused on the experiences of Black people on her street, highlighting one experience for each house on the block.

A Street in Bronzeville was published in August, 1945. It was an instant success and achieved national recognition. And Gwendolyn received a Guggenheim Fellowship as a result of the success. The Guggenheim Fellowship provided her with the ability to focus on writing full time. The result was her second book of poems, Annie Allen, which was published a few years later in 1949. It was a collection of poems about a Black girl growing up in the South Side of Chicago.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Gwendolyn was born in Topeka, Kansas, but grew up in Chicago. Shortly after she was born, her parents sought a better life and more opportunities in the North and moved to Chicago during the Great Migration. Her family settled in the South Side of Chicago, along with thousands of other Black families.

Gwendolyn Brooks, Library of Congress

Gwendolyn’s father was a janitor and her mother was a teacher. They both inspired her passion for reading and introduced her to poets such as William Wordsworth and John Keats. Her mom took her to the library regularly, encouraged her when she started writing poetry at age 7, and helped her submit poems to various magazines and contests.

Gwendolyn was 13 when her first poem was published — “Eventide” was featured in the American Childhood magazine in 1930. Then, she was featured regularly in the Chicago Defender (a famous Black newspaper) as a teenager. In fact, she became an adjunct member of its staff and managed a weekly poetry column called “Lights and Shadows.” By the time she graduated high school, Gwendolyn had already published about 100 poems.

Throughout high school, Gwendolyn attended 3 different schools — Hyde Park High School (all-white school); Wendell Phillips Academy High School (all Black-school); and Englewood High School (an integrated school). Each school provided her with a different view of race and discrimination within Chicago. After high school, Gwendolyn attended Wilson Junior College and graduated in 1936 with a degree in English.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- Gwendolyn Brooks was born on June 7, 1917 in Topeka, Kansas. Her parents moved to Chicago when she was about 1 month old.

- Gwendolyn married Henry Blakely in 1939. They had two children, Hank and Nora. She lived in Chicago’s South Side her entire life.

- After publishing A Street in Bronzeville, Gwendolyn was selected as one of Mademoiselle magazine’s “Ten Young Women of the Year” and became a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

- Her second book of poetry, Annie Allen, won Poetry magazine’s “Eunice Tietjens Prize” and the Pulitzer Prize.

- Gwendolyn taught creative writing at a number of colleges — Columbia College in Chicago, Chicago State University, Elmhurst College, Northeastern Illinois University, Clay College of New York, Columbia University and the University of Wisconsin.

- President John Kennedy invited her to read at a Library of Congress poetry festival in 1962.

- Gwendolyn served as the Poet Laureate of Illinois from 1968-2000 and Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress from 1985-1986. She was also selected by the National Endowment for the Humanities as the 1994 Jefferson Lecturer, the highest award in the humanities given by the federal government.

- Gwendolyn received a number of awards over her lifetime: fellowships from the Academy of American Poets and the Guggenheim Foundation; recipient of the American Academy of Arts and Letters Award, the Frost Medal; the Shelley Memorial Award from the Poetry Society of America; the National Medal of Arts; lifetime achievement award from the National Endowment for the Arts; and induction into the National Women’s Hall of Fame.

- Gwendolyn received honorary degrees from over 70 colleges and universities. Her papers are at the University of Illinois.

- Gwendolyn died of cancer on December 3, 2000 in Chicago.

Want to Know More?

Brooks, Gwendolyn. Conversations with Gwendolyn Brooks. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2003.

Kent, George. A Life of Gwendolyn Brooks. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 1993.

Gwendolyn Brooks, The Poetry Foundation (https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/gwendolyn-brooks).

Gwendolyn Brooks, American Academy of Poets (https://poets.org/poet/gwendolyn-brooks).

Gwendolyn Brooks, Illinois State Library (https://www.ilsos.gov/departments/library/center_for_the_book/gwendolyn_brooks.html).

Gwendolyn Brooks, U.S. Consultant in Poetry, 1985-1986. Library of Congress (https://www.loc.gov/item/n50041281/gwendolyn-brooks/)

“Frost? Williams? No, Gwendolyn Brooks,” The Pulitzer Prizes (https://www.pulitzer.org/article/frost-williams-no-gwendolyn-brooks).