Culture Changer

She was one of the first to recognize the genius of modern artists like Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso, and in her passion for their work, created one of the most influential private collections of modern art in America. The same Baltimore society that initially shunned her because of her “eccentric“ and unconventional taste in art now hosts thousands of visitors per year at the Cone Wing of the Baltimore Museum of Art. Transport yourself to 1930 and spend a day with Matisse and Etta Cone…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

Etta Cone looked out the window of her eighth floor apartment. It was cold and rainy in Baltimore that day, December 17, 1930. And she was impatient for her visitor, Henri Matisse, to arrive. She still couldn’t believe he was visiting her small home, which was bursting at the seams with his art. By then, Matisse was a famous artist and could have stayed anywhere. But he chose to spend the evening with his friend and patron, Etta.

Etta and her sister, Claribel, had spent most of their adult life creating an impressive collection of modern art. Over 3,000 pieces of art in total. The women were bold and brave in their purchases over the years. They were one of the first patrons of the modern art movement in France. And they supported artists, such as Matisse and Picasso, when they were ridiculed and broke.

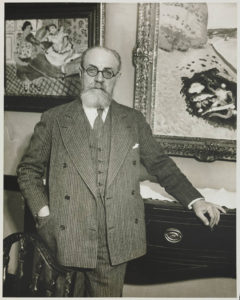

Henri Matisse in Etta’s apartment, Baltimore Museum of Art

Matisse arrived just before lunch. Etta gave him a tour of the art stuffed into the apartments. Matisse was charmed by the display and thought it was the perfect setting to showcase his work. He was also astounded by the sheer volume of the collection. He hadn’t realized how much the sisters, whom he called “My Baltimore Ladies,” had purchased over the years. They owned around 500 works by Matisse, one of the largest collections of his work anywhere in the world. In fact, their purchases documented over 50 years of Matisse’s career.

Etta and Matisse attended a concert in the evening, then chatted into the night. They argued about whether Etta made Matisse or Matisse made Etta. Etta described the moments when art made the biggest impression upon her and Matisse talked about his struggle to find his style. It was clear that they had deep admiration and mutual respect for each other.

Matisse’s appearance in Baltimore created quite a stir. While staying with Etta, he was interviewed by a reporter from the Baltimore Sun newspaper. The piece, along with a cartoon, ran the next day. And Matisse’s visit cemented Etta’s status as a serious collector of art.

Etta’s support of Matisse was needed in 1930 more than ever. It was the beginning of the Great Depression and many people stopped purchasing art. But Etta’s family wealth was stable and she continued her steady pace of collecting. In fact, she bought some of the most important works in the collection during the 1930s.

The two were such close friends that Etta purchased most of Matisse’s work directly from him or his family. Matisse set aside paintings that he thought she would like and offered her the first option to purchase them. She relied on his expertise as well and routinely asked him what pieces might fit best into her collection. In fact, she once wrote to Matisse that “knowing you and your great work was one of the great influences” of her life.

The Power of the Wand

Eventually, the world caught up with the Cone sisters’ appreciation of modern art. By 1950, art experts acknowledged that Etta and Claribel had created the most important modern art collection in America. Etta donated the Cone Collection to the Baltimore Museum of Art upon her death, as well as $400,000 to provide a home for the collection (the new wing opened in 1957). Today, the Cone Collection is valued at over $1 billion.

In honor of the anniversary of woman’s suffrage, the Baltimore Museum of Art will celebrate its heritage of women leaders throughout 2020. And the museum plans to dedicate the entire year to purchasing only art work by women artists. It will also highlight women in its programming, with more than 10 exhibits of women artists.

In honor of the anniversary of woman’s suffrage, the Baltimore Museum of Art will celebrate its heritage of women leaders throughout 2020. And the museum plans to dedicate the entire year to purchasing only art work by women artists. It will also highlight women in its programming, with more than 10 exhibits of women artists.

Over the years, women artists have been drastically under-represented in America’s museum collections. Teen artists like Autumn De Forest are doing their part to close this gender imbalance. Autumn was born into a family of artists and started painting when she was 5 years old. In 2016, she became the youngest artist to have a solo exhibition (“The Tradition Continues”) at the Butler Institute of American Art. In 2015, she earned the International Giuseppe Sciacca Award for Painting and Art from the Vatican. Her art hangs in museums next to American male artists such as Normal Rockwell, Andy Warhol and Jackson Pollock.

Her Yellow Brick Road

Etta and Claribel saw Matisse’s work for the first time on October 18, 1905. They attended the opening night of the Salon d’Automne in Paris. There was a small room that held art created by the “independents,” including that of Matisse. The walls were covered in large canvases with bold brushstrokes, vivid colors and a radical style. People reacted strongly — they laughed, pointed, shouted, and even scratched at the paintings. The Cone sisters didn’t know what to think. They were shocked at the spectacle, but also intrigued.

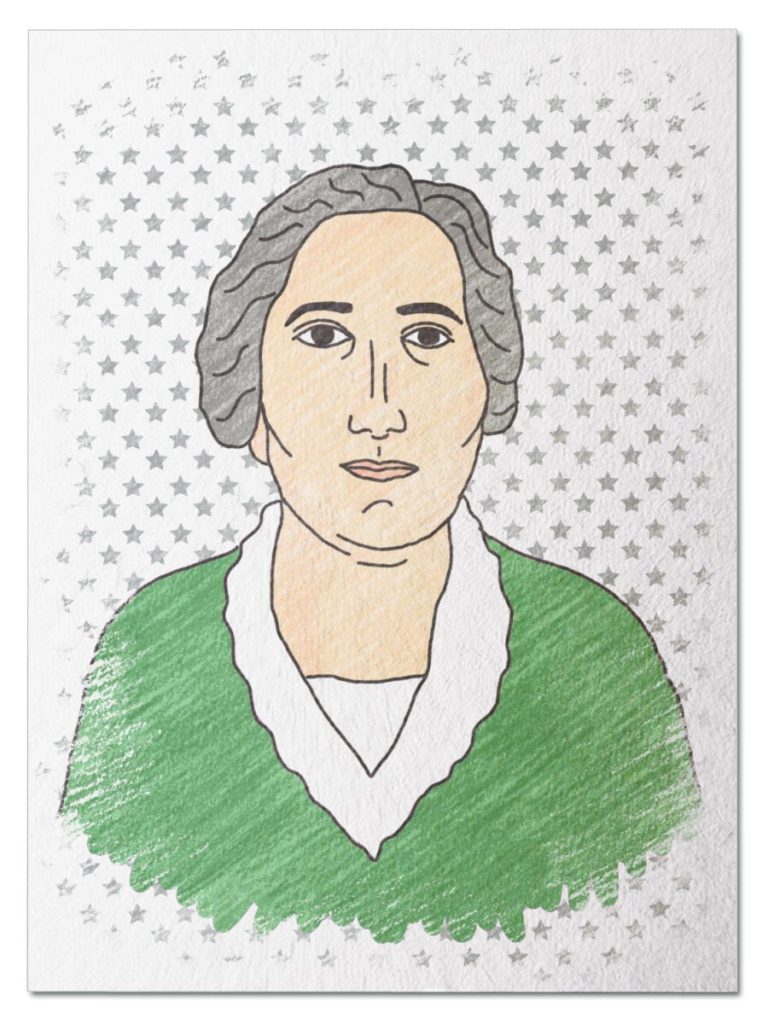

Sketch of Etta Cone, by Pablo Picasso, Baltimore Museum of Art

Etta visited Matisse’s studio a few months later, on January 15, 1906. She purchased two drawings that day. It was the first of many visits and the beginning of an important friendship. Etta was one of the earliest of patrons of Matisse’s work — her first painting was Yellow Pottery from Provence. It didn’t matter that he was vilified and ostracized by the art world at the time. In fact, he was so poor that he briefly considered burning his canvases to get the insurance money.

During that winter, Etta rented an apartment in Paris and was on her own for the first time in her life. She enthusiastically embraced all that Paris had to offer and learned about modern art every chance she got. She attended auctions, wandered through museums, made a lot of connections, and visited both galleries and artist studios. And she bought a wide variety of work, including Matisse, Picasso, Cezanne, Renoir and Manet. She bought art that she loved, regardless of what anyone else thought about it.

Etta and Claribel began to collect art in earnest in the 1920s, after the turmoil of World War I was over. They spent every summer in Paris and added art to their collection. Etta visited Matisse’s studio every summer and selected paintings to purchase. Acquiring Matisse’s work was her priority for many years. And she stuck by him even though his work was controversial.

The sisters spent their winters back in Baltimore. Etta, Claribel, and their brother Fred all rented adjoining apartments. Eventually, Claribel’s apartment became so packed with her collection that she rented another apartment to sleep in. While at home, Etta and Claribel studied aesthetics and art history. They were lifelong students and had an inexhaustible thirst for knowledge — they collected books on art history and attended classes at Johns Hopkins University.

The sisters spent their winters back in Baltimore. Etta, Claribel, and their brother Fred all rented adjoining apartments. Eventually, Claribel’s apartment became so packed with her collection that she rented another apartment to sleep in. While at home, Etta and Claribel studied aesthetics and art history. They were lifelong students and had an inexhaustible thirst for knowledge — they collected books on art history and attended classes at Johns Hopkins University.

Claribel passed away in Switzerland at age 64. She left her entire collection to Etta in her will, expressing the hope that she would donate it to the Baltimore Museum of Art IF the city became more accepting of modern art. After Claribel died, Etta continued to travel and acquire art to complete their collection.

The Cone sisters were shunned by Baltimore society for years. People ridiculed them for their eccentric taste in art. Etta was oblivious to the criticism, however. She followed her passion, took risks, and purchased art that spoke to her. And we all benefit from her daring choices.

Brains, Heart & Courage

The Cone sisters grew up in a proper Victorian household. Their family eventually supported their unconventional paths in life, however. The sisters both owned stock in the family business, which gave them an annual income to spend on travel and art.

Claribel was determined to be independent and became one of the first women doctors in America. She specialized in pathology and conducted medical research in both America and Germany. It was hard for a woman to have a medical career back then, however, and her career ended during World War I. Little did she know it was the first of many daring purchases.

Etta and Claribel in Europe, Baltimore Museum of Art

Etta got her first taste of independence when she traveled to New York City in 1898. Her brothers had given her $300 to spend on renovations to the family home. Today, that would be the equivalent of about $9,000. She was expected to purchase new rugs, curtains, and furniture. Instead, Etta spent all the money on art. She bought five impressionist paintings by American artist Thomas Robinson. It was a rebellious act that shocked her family.

Etta took her first trip to Europe in 1901 when she was 30 years old. And it opened her eyes to new possibilities. While there, she found a passion for European art. Etta also enjoyed the freedom that came with travel — it was an escape from the confining role of a single woman in America.

Just the Facts

- Etta was born on November 30, 1870 in Tennessee. She graduated from Western Female High School in 1887 and lived at home, helping to care for her parents and brothers. She was a talented piano player and studied French.

- Claribel was born on November 14, 1864. She attended the Woman’s Medical College of Baltimore and graduated top of her class in 1890. Then, she did graduate work at Johns Hopkins Medical School, Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, and University of Pennsylvania.

- Their father, Hermann Cone, emigrated from Germany and started a grocery store. He married Helen Guggenheimer and they had 13 children. The family moved to Baltimore in 1870 and were welcomed into its robust Jewish community.

- Eventually, all the brothers worked in the family business. They sold the grocery stores and bought struggling cotton mills throughout the South. They went on to build a textile empire — Cone Mills provided denim to the Levi Strauss company and supplied khaki fabric to the armed services during World War I.

- Claribel spent 15 years living in Germany. She died of pneumonia in Lausanne, Switzerland on September 20, 1929. She continued to buy art until the day she died, completing a purchase that very morning.

- Etta traveled to Europe over 20 times during her life.

- Etta and Claribel were the subject of Gertrude Stein’s essay, “Two Women.”

- The Cone Collection was internationally known by 1940. Etta gave countless tours of the collection in the apartments and loaned works to museums. Over ten museums were courting Etta, hoping to receive the Cone Collection after her death. But her devotion to her home city won out in the end.

- Etta died on August 31, 1949 at age 78.

- The Cone Wing of the Baltimore Museum of Art was completed in 1957 and work from the Cone Collection has been on view ever since.

- The Cone sisters’ apartment were virtually reconstructed by the Baltimore Museum of Art and the University of Maryland (tour is on YouTube).

- The Cone Sisters were the subject of the play, “All She Must Possess” (review in DC Theater Scene).

Want to Know More?

Fillion, Susan. Miss Etta and Dr. Claribel: Bringing Matisse to America. Boston: David Godine, 2011.

Gabriel, Mary. The Art of Acquiring: a portrait of Etta & Claribel Cone. Baltimore: Bancroft Press, 2002.

Hirschland, Ellen and Nancy Hirschland Ramage. The Cone Sisters of Baltimore: Collecting at Full Tilt. Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2008.

Pollack, Barbara. The Collectors: Dr. Claribel and Miss Etta Cone. Indianapolis : Bobbs-Merrill, 1962.

Richarson, Brenda. Dr. Claribel & Miss Etta: the Cone Collection of the Baltimore Museum of Art. Baltimore: Baltimore Museum of Art, 1985.

The Claribel Cone and Etta Cone Papers are held at the Baltimore Museum of Art.