Brilliant Businesswoman

In the late 18th century, it was considered against the will of God to teach girls math, so she taught herself geometry when she was 12. She grew up to be a pioneer for girls’ schooling, proving to the world that it wasn’t dangerous for women to be educated. She lobbied legislatures, impressed presidents, and traveled the world promoting her radical ideas for opening the world of knowledge to girls, Travel back in time to 1821 New York and celebrate the opening of the Troy Female Seminary with Emma Willard…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

Emma (Emma Willard School)

Emma Willard felt defeated. The New York Legislature again had refused to provide her school, the Waterford Academy for Young Ladies, with a public endowment after years of promises. The school was so successful, and her students so accomplished, that she had been confident of success this time, even breaking her usual rule to not spend more than tuition could cover. Emma feared she would not receive public funding unless she could grow public demand for girls’ education. Much of society still believed that educating girls was dangerous.

Not long afterward, opportunity knocked. The City Council of Troy, NY, a progressive manufacturing town, asked if Emma would open a girls’ academy there, and passed a special tax to raise $4000 to fund it. Emma jumped at the chance and moved Waterford Academy into a remodeled 22 room coffee house. The Troy Female Seminary opened in September 1821, attracting 90 students from seven different states, including 29 Troy residents. Emma offered financial aid in exchange for an agreement to teach after graduation. She liked hiring former students because they knew how hungry girls were for knowledge.

Troy Female Seminary (Rennselaer County Historical Society)

Emma set out to prove that girls’ health and happiness would not be undermined by education. She structured the school day to include time for study, meals, exercise, and free time. Her students had access to all subjects, including those which were rarely available to girls, like math, science, rhetoric, philosophy, and exercise. Emma bundled history, literature and geography together into one class so students could immerse themselves in different cultures. Traditional subjects like art, music, language and dancing were part of the schedule as well.

Emma made a point of hosting two public exams a year to demonstrate that higher education wasn’t dangerous for girls and that they were capable of learning difficult concepts. The annual exam in July lasted 8 days and attached a big audience of parents, friends, community leaders, teachers, clergy, and legislators. Students stood to answer questions and solve problems posed by their teachers. They drew maps by memory on blackboards with colored chalk. The walls of the school were filled with their art. During breaks, students played instruments and sang for the crowd.

Emma’s curriculum quickly became known as the most complete course of study for girls in the country. After her husband died in May 1825, Emma had to learn how to keep the books. She was able to orchestrate a major expansion of the school in 1826. An Emma Willard school certificate was soon considered the highest recommendation a teacher could have. Graduates returned to their towns and established schools all over the country.

Emma’s curriculum quickly became known as the most complete course of study for girls in the country. After her husband died in May 1825, Emma had to learn how to keep the books. She was able to orchestrate a major expansion of the school in 1826. An Emma Willard school certificate was soon considered the highest recommendation a teacher could have. Graduates returned to their towns and established schools all over the country.

The Power of the Wand

Emma’s passion sparked a revolution in girls’ education not just in the United States, but around the world. The Marquis de Lafayette, who had three daughters, visited the school multiple times and he brought her ideas to France. Emma persuaded the President of Colombia to open a female seminary in Bogota, and founded a women’s seminary in Greece with proceeds from the sale of her European travel journals.

Emma WIllard School today (Emma Willard.org)

Troy Seminary was renamed The Emma Willard School for Girls in 1895. It moved to a new campus on Mount Ida in Troy in 1910. The Emma Willard School is still one of the leading girls’ schools in the country and is a living testament to the difference Emma’s vision is still making for girls and women today. “Honoring its founder’s vision, Emma Willard School proudly fosters in each young woman a love of learning, the habits of an intellectual life, and the character, moral strength, and qualities of leadership to serve and shape her world.”

Her Yellow Brick Road

Emma was teaching in in Middlebury, Vermont when she met and married John Willard. John’s nephew attended the college in town. Emma read his textbooks and realized how much knowledge was kept outside the reach of most women. She believed that society would benefit if women were better educated.

The Willard House in Middlebury (Wikicommons)

After the Willards suffered a financial setback during the War of 1812, Emma proposed opening a boarding school for girls in their home. John swallowed his pride and said yes. Emma planned to offer academic subjects like math, history and sciences, but her marketing emphasized “appropriate” subjects for girls like music, drawing, and handwriting so the public wouldn’t immediately object. Even so, Emma worried she would be considered “a visionary almost to insanity.”

Emma opened the Middlebury Female Seminary in Spring 1814. She couldn’t call it a college because girls weren’t supposed to go to college. The school was a success from the start, attracting 70 students, including 40 boarders. Emma asked Middlebury College if her students could observe classes and Emma could attend a series of exams to learn how they were done. The College said no.

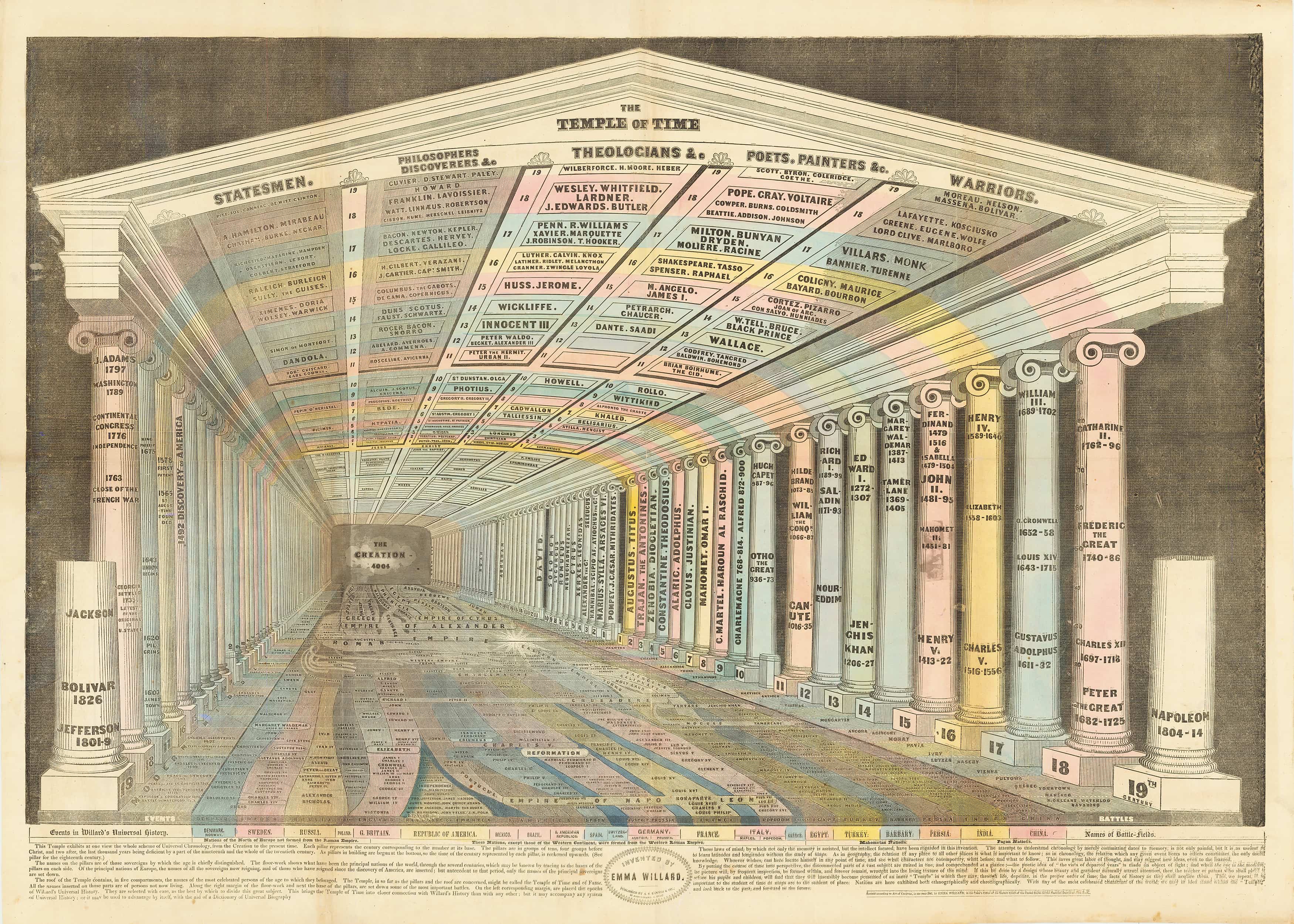

Emma’s Temple of Time method of teaching geography & history (Emma Willard)

Emma instead developed her own three part teaching method: 1) Understand (teacher explains and illustrates), 2) Remember (students recite), and 3) Communicate (student becomes the teacher). She came up with her own exams and invited professors and townspeople to attend them to see how well girls could do with college level work. Emma collected her methods and research into a Plan of Education.

At the time, there was considerable government funding for men’s colleges, and Emma asked that the same support be given to women’s schools. The Vermont government repeatedly refused. Emma changed gears and sent a handwritten copy of her Plan of Education to the New York Governor in 1818, attended its next legislative session, and read her plan to many representatives. She was persuasive: the New York legislature approved a charter for the Waterford Academy for Young Ladies, which was the first law in the United States supporting higher education for women. However, it voted down a $5000 endowment.

Emma (NY Public Library)

Emma was encouraged by the charter, moved her students to Waterford, NY, and renewed her fight for funding. She wrote and published the pamphlet “An Address to the Public; Particularly to the Members of the Legislature of New York, Proposing a Plan for Improving Female Education.” In it, she asserted that educating women was patriotic. She leveraged the sexism of male decisionmakers by arguing that educated women would raise smarter sons, who in turn would be better positioned to preserve the new American form of government. She also pointed out that schools could pay women teachers less, educate more children, and set men free for other work.

Emma then made her pitch for what these schools needed: a large building with a lab, maps, globes, musical instruments, a teaching staff, a Board of Trustees, and state funding. She proposed four main areas of study: Religious and Moral, Literary, Domestic, and Ornamental (music, art, dancing, handwriting). She tucked academic subjects like literature, history, math and science into the Literary category to ensure their inclusion without drawing too much attention to the novelty of allowing women to study them.

The pamphlet caused a stir. She received favorable responses from many, including President Monroe and former Presidents Adams and Jefferson. But there were many opposed to her ideas, who asked questions like: Would women still cook and sew? Would women no longer be charming if they were educated? Would women try to compete with men and upset the order of things? Would the stress of education make women ill and unable to have children?

The pamphlet caused a stir. She received favorable responses from many, including President Monroe and former Presidents Adams and Jefferson. But there were many opposed to her ideas, who asked questions like: Would women still cook and sew? Would women no longer be charming if they were educated? Would women try to compete with men and upset the order of things? Would the stress of education make women ill and unable to have children?

The key to implementing the Plan was financial support. Emma repeatedly lobbied the New York Legislature to reconsider an endowment. She trained former students to teach at Waterford so it could grow and attract more students and tuition dollars. She started writing textbooks that reflected her teaching philosophies, which turned into a profitable endeavor, both financially and for Emma’s reputation as an educator.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Emma grew up in the late 18th century, when the general public believed educating girls was dangerous because they weren’t biologically equipped to handle difficult concepts. There was a narrow set of acceptable subjects for girls, including the Bible, French, painting, sewing, and playing the piano. Teaching girls how to do math was considered to be contrary to the will of God. That didn’t make sense to Emma, and she taught herself geometry when she was 12 years old.

Painting of daily life in the 18th century (National Geographic)

Her family lived on a busy farm in Connecticut. They made their own wool, linen, soap, and maple syrup. They canned fruits and vegetables and spent their evenings by the fire listening to their parents read aloud. Emma’s dad often led conversations about his experiences in the Revolutionary Army and his post-war work in Connecticut’s General Assembly. All the children, boys and girls alike, were expected to participate in family conversations about morality, religion, politics, and current events.

Connecticut was one of the first colonies to provide elementary public education. Initially only boys were allowed to attend, but Emma’s dad helped persuade their school to educate girls in the summer while the boys were in the fields. The girls did so well that eventually they were allowed to attend all year. Emma learned an important lesson: you need to get your foot in the door. Once you do, you can work to open the door wider.

Emma’s association supported women educators (NY Public Library)

When Emma was 15, she started going to an academy that had recently opened in a neighboring town. It was run by a Yale graduate with a gift for teaching and drew boys and girls from a wider area. Emma later said “I believe that no better instruction was given to girls in any school at that time, in our country.” Once Emma was 17, she was asked to teach at the village school. She loved the work, but soon realized that in order to be an excellent teacher, she needed more education herself. She taught winter and summer and studied in spring and fall.

Emma’s passion for learning showed, and she developed a reputation as a unique and inspiring teacher. Several different schools offered her a position, including a group of citizens in Middlebury, Vermont who were planning to re-open a girls’ academy that had recently closed. The opportunity to be part of something new intrigued Emma and she decided to accept the offer.

Just the Facts

- Emma was born on February 23, 1787 in Berlin, Connecticut. She was the 16th of 17 children of Samuel Hart, a descendant of Pilgrims who founded the cities of Hartford and Farmington. Her mom was Samuel’s second wife, Lydia Hinsdale.

- Emma married John Willard in 1809 and became a stepmother to four children. She had one more son, John Hart Willard, in September 1810.

- The first textbook Emma wrote was for math. She started there because she believed that math, above all other subjects, taught women to “think for themselves in an orderly way, help them to impersonalize their problems and solve them on the basis of abstract truth.”

- Emma revolutionized the study of geography, by writing a text for her school where, instead of the usual uninspiring lists of facts, she included vivid descriptions of countries accompanied by maps and charts. Her new approach attracted the notice of a well-known geographer. The two of them collaborated on the very successful 1824 textbook “Universal Geography: Ancient and Modern.”

- Emma was also an innovator in history texts. She believed that the Constitution, Declaration of Indepedence & Washington’s Farewell Address were American scriptures to study and discuss. Her textbook “Republic of America” also included maps to illustrate each lesson and made explicit connections between history and current events.

- In 1833, there were 79 incorporated colleges and universities for men in the United States, and zero for women. “American Ladies Magazine” called for Troy Seminary to be the first, stating “Men of America, shall this neglect of your daughters be perpetual?”

- Emma started the Willard Association for the Mutual Improvement of Female Teachers in 1837. Its purpose was to facilitate the sharing of information, curriculum, and training of teachers across the country.

- Emma retired from running the Troy Female Seminary in 1838, handing the reins to her son and daughter-in-law. She married again shortly afterward, but separated from her new husband nine months later. Fortunately, she had insisted on a marriage agreement, so she kept her property.

- Emma spent much of her time after retirement traveling around the country helping to improve public school systems. She advocated for the professionalization of teaching, with job stability and better pay.

- Emma stayed involved with the Troy Female Seminary throughout her life. In 1852, she again petitioned the legislature for an endowment and was again denied.

- Emma’s Temple of Time textbook won a gold medal at the 1851 World’s Fair.

- Emma published several more textbooks, including Chronographer of Ancient History, Historic Guide to the Temple of Time, A System of Universal History in Perspective, and Last Leaves of American History. Most of her textbooks had multiple editions.

- Emma was a pioneer in studying human anatomy at a time when women were considered too delicate for the subject. She spent years working on her theory that breathing pushed blood through the body, even attending autopsies to observe the connection between heart and lungs. She published her “Theory of Circulation by Respiration,” but was convinced that if the theory was accepted, a woman would not get credit. She was right, although she eventually was offered membership in the Association of Advancement for Science.

- Emma died on April 15, 1870 at age 73.

Want to Know More?

Willard, Emma. Journal and Letters From France and Great-Britain. (N. Tuttle Printing 1833).

Lutz, Alma. Emma Willard, Pioneer Educator of American Women (Greenwood Press 1983).

Scott, Anne Firor. “Emma Willard: Feminist” (CUNY Women’s Studies Quarterly 1979).

Vinci, Anthony. “Emma Hart Willard: Leader in Women’s Education” (Connecticut History.org Feb 23, 2017)