Brilliant Businesswoman

She fell in love with a civil engineer from a family of bridge builders and expected to live a quiet life listening to her husband’s stories from work. Instead, when he fell ill, she stepped into his role as Chief Engineer of the Brooklyn Bridge and became the driving force behind it. She wasn’t formally trained as an engineer, but successfully shepherded the construction of the world’s longest suspension bridge and connected Manhattan and Brooklyn. Hop into an open air carriage in 1883 for the first trip across the Brooklyn Bridge with Emily Warren Roebling at The Glinda Factor.

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

Emily Warren Roebling laughed as she looked down at the white rooster in her lap. She was riding across the Brooklyn Bridge – the first person to ever do. The rooster was a traditional symbol of victory, but she just hoped it didn’t peck her or try to get out of the open air carriage! She waved to the engineers and construction workers who had gathered on this beautiful spring day to watch the first trip across the world’s longest suspension bridge. There was an assistant engineer assigned to watch the bridge to see if it would vibrate with the horses’ trotting – it didn’t. This was one of the final tests before the Bridge opened to the public.

Emily (Brooklyn Museum)

Not many people outside of those present knew that Emily had been the unofficial Chief Engineer of the Brooklyn Bridge for the last 11 years. Her husband, Washington, was technically in charge, but fell seriously ill three years into the project. Once he was too sick to visit the construction site, Emily became his liaison with the crew. At the beginning, Wash dictated instructions for her to write down and deliver to the assistant engineers. She would inspect the progress, ask questions, and report back to Wash at home, where he was doing his best to monitor the construction from his bedroom in their Brooklyn Heights apartment. Emily had set up a telescope at the window.

As Wash’s condition deteriorated, Emily took on more responsibility for the Bridge. She studied the engineering principles involved, including how to calculate catenary curves and assess how much stress a structure could withstand. She became an expert on the strength and durability of steel, iron, granite, concrete, and sandstone. The crew began to go directly to Emily with their questions. Soon the subcontractors did as well. After a design change, when steel mill representatives were struggling with how to construct the new shapes specified, they came to the house to ask Wash their questions in person. He was unable to meet with them and Emily sketched the design and specifications for them herself.

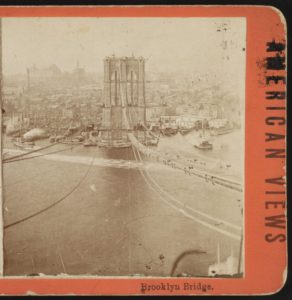

Brooklyn Bridge under construction (Library of Congress)

Emily worked with suppliers to negotiate prices, terms, and deliveries. She ensured the workers were paid and conditions were as safe as possible. She was the voice of the Bridge when the Board of Trustees required a report. And she did all of this while serving as Wash’s primary caretaker. She limited his exertions whenever possible, and when it avoiding people was impossible, she helped him dress and get out of bed so he could look strong and in control.

While most people didn’t realize the extent of Emily’s role, there were whispers about her frequent presence at the construction site. She endeavored to keep her participation as as quiet as possible, because society wasn’t completely comfortable with the idea of a woman playing engineering a suspension bridge over the East River that would be used by thousands of people every day. Rumors started flying that Wash’s problem was mental illness, because only an insane man would give his wife this much responsibility.

The assistant engineers knew better – they believed in Emily and respected her. But at one point near the end of the project, some Trustees forced a vote to fire Wash because of his absences. Emily had to do some deft political maneuvering to convince the Board to stay the course, and Wash survived on 10-7 vote.

The assistant engineers knew better – they believed in Emily and respected her. But at one point near the end of the project, some Trustees forced a vote to fire Wash because of his absences. Emily had to do some deft political maneuvering to convince the Board to stay the course, and Wash survived on 10-7 vote.

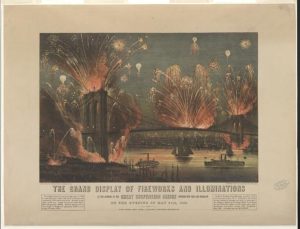

Ten days after Emily and the rooster made their way across the Brooklyn Bridge, it opened to the public. The ceremony on May 24, 1883 was a huge event. Ticketed spectators climbed the stairs to line the road that now spanned the East River. Hundreds of thousands more gathered on the riverbanks. They watched a group that included President Chester Arthur and Governor Theodore Roosevelt walk from Manhattan to Brooklyn on the Bridge.

Brooklyn Bridge

There was a military band, a formal dedication and several speeches, including one by iron manufacturer Abram Hewitt, who publicly acknowledged Emily’s role. He proclaimed that “the name of Emily Warren Roebling will…be inseparably associated with all that is admirable in human nature and all that is wonderful in the constructive world of art” and that the Bridge was “an everlasting monument to the self-sacrificing devotion of a woman and of her capacity for that higher education from which she has been too long disbarred.”

Emily left the celebration early to return home and host a reception so Wash could be part of the celebration. It had been 14 years since construction began, and as Emily watched the celebratory fireworks with her husband and guests, she wondered how history would write the story.

Currier & Ives drawing of Brooklyn Bridge Grand Opening Celebration (Library of Congress)

One answer came in the plaque on the Bridge tower on the Brooklyn side which reads: “The builders of the bridge dedicated to the memory of Emily Warren Roebling 1843-1903 whose faith and courage helped her stricken husband Col. Washington A. Roebling, C.E. 1837-1926 complete the construction of this bridge from the plans of his father John A. Roebling, C.E. 1805-1869 who gave his life to the bridge. ‘Back of every great work we can find the self-sacrificing devotion of a woman.’”

The Power of the Wand

The Brooklyn Bridge is still one of the most iconic suspension bridges in the world. It took 600 workers 14 years to build it. And sadly, 27 of those workers, including Emily’s father-in-law, died on the job. On average, 144,000 vehicles travel across it every day, which is even more remarkable when you consider it was engineered and constructed 138 years ago, when the primary vehicle crossing it was a horse drawn carriage!

Today, many professional engineering societies host model bridge building competitions for teenagers. The Brookhaven National Laboratory hosts an annual competition for students in Long Island, NY. The National Society of Professional Engineers – Colorado hosts one as well. And the Illinois Tech website has advice for how to host your own bridge building contest at your school.

Her Yellow Brick Road

Emily’s father in law, John Roebling, was a well-known engineer and bridge designer. His dream was to build a suspension bridge over New York’s East River that would connect Manhattan and Brooklyn. John came up with a design – two towers with 14,000 feet of steel cables supporting a roadway nearly 6000 feet long. He began lobbying the government for the bridge in 1857, and finally succeeded after the harsh winter of 1866-67, when the East River froze, making ferry travel between the cities very difficult. When the bill to fund the bridge passed in 1867, John was appointed Chief Engineer. He estimated construction would take 4 years to complete and cost $4 million – it eventually took 14 years and $15 million.

Currier & Ives Drawing of the Bridge

John asked his son Washington – Emily’s husband – to travel to Europe to study the suspension bridges of England, Wales, Germany and France. Emily, pregnant at the time, went with Wash to help him. The focused on learning about caissons, an advanced technique developed in Europe. A caisson was a giant upside down box lowered into the water where the bridge foundations were laid. Engineers and laborers accessed the caisson from a shaft connecting it to the riverbank and were able to stay dry while working inside it. Pressurized air was pumped in, so engineers could access depth that until now had been impossible to reach, and laborers could stay underwater for extended periods of time digging into the riverbed to find solid rock. When the digging is done, the caisson is anchored and filled with concrete. The towers that support the weight of the bridge cables and roadway are built on them.

In summer 1869, John died shortly before construction was scheduled to begin. He had contracted tetanus after an accident he suffered while scouting bridge tower locations. Wash took over the job of chief engineer, and oversaw the design of caissons based on those he and Emily saw in Europe, made of wood and iron. They were submerged into the river, with granite blocks on top of it to push it down to the bottom. Wash’s crew spent hours in cramped conditions inside the caisson digging into the riverbed. But it paid well – $2 a day – so there was never a labor shortage.

Many of the workers became ill with a disease they referred to as caisson disease (now known as “the bends”). Abrupt changes in pressure, which can happen when people rapidly descend and ascend into water depths, often wreak havoc on the body. Wash spent much of his time in and out of the caisson to consult with the workers underwater and on land. He started having severe attacks of the bends in 1870, just as the Brooklyn side caisson was completed. But he shrugged off his health issues and continued entering the caisson on the Manhattan side. By the time it was finished in 1872, Wash was in constant pain, with loss of balance and failing eyesight.

Many of the workers became ill with a disease they referred to as caisson disease (now known as “the bends”). Abrupt changes in pressure, which can happen when people rapidly descend and ascend into water depths, often wreak havoc on the body. Wash spent much of his time in and out of the caisson to consult with the workers underwater and on land. He started having severe attacks of the bends in 1870, just as the Brooklyn side caisson was completed. But he shrugged off his health issues and continued entering the caisson on the Manhattan side. By the time it was finished in 1872, Wash was in constant pain, with loss of balance and failing eyesight.

Wash could no longer be on site as Chief Engineer and there was talk about replacing him with someone else. Emily visited the President of the New York Bridge Company and convinced him to let Wash remain Chief Engineer while she helped be the liaison. He agreed, on the condition that the construction go smoothly. If there were issues, the deal was off.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Emily was a Warren, which meant a lot in her hometown of Cold Spring, New York – a town near West Point about 50 miles north of Manhattan. Her family had settled in Cold Spring before the Revolutionary War. The Warrens lived in a big house in town, which they needed for their 12 children! Emily was the 11th child, so grew up with many older brothers and sisters to idolize. Her older brother Gouverneur was 13 years older than her, and while he was away for school and in the military for much of her childhood, when he was home for the holidays the two of them grew very close. They both loved horses and had curious minds.

Emily upon graduation from NYU Women’s Law Program (NY Historical Society Library)

Once Governeur had established himself in the military, he offered to pay for his younger siblings’ education. He noticed Emily’s aptitude for math and science and arranged for her to go to boarding school at the Georgetown Visitation Convent in Washington, D.C. when she was 15. Emily loved studying there, as the curriculum included several “boy” subjects like algebra, geometry, geology, geography and chemistry in addition to the home economics, needlework and art classes girls were expected to take. She graduated with top honors.

Gouverneur was a General in the Union army during the Civil War. In February 1864, Emily went to visit him and attended a military ball where she met one of the soldiers on his staff, a civil engineer named Washington Roebling. Wash was the son of a famous engineer known for designing suspension bridges, including the one over Niagara Falls. It was love at first sight. When Emily returned to Cold Spring, they spent the next eleven months writing love letters back and forth. They only saw each other one again before they were married in January 1865.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- Emily was born on September 23, 1843, in Cold Spring, New York.

- Emily had one son, John. He was born while she and her husband Washington were traveling in Europe, in the same German town where Wash’s father was born.

- It took some time for people to have confidence that a suspension bridge over such a big river could be safe. A week after the Bridge opened to the public, on May 30, 1883, a group of people on the stairs to the Bridge heard a scream from someone who tripped and fell and thought the bridge was collapsing. The ensuing stampede killed 12 people. There was an investigation which confirmed the Bridge was safe, and the deaths were caused by the panic.

- Circus entrepreneur P.T. Barnum suggested that he could prove the Bridge was safe by marching his elephants across it. The city agreed, and on May 17, 1884, 21 elephants (led by the most famous one named Jumbo) and 17 camels made the trip across the Bridge. The public was convinced and the panic subsided.

- After the Brooklyn Bridge construction was finished, Emily and Wash moved to Trenton, New Jersey. They built a house there and Emily managed its construction.

- Emily studied law at New York University in a program designed for businesswomen called the NYU Women’s Law Class. She received a certificate from the program in 1899 at the age of 56. At the graduation ceremony, she presented her essay “A Wife’s Disabilities,” which criticized laws that discriminated against married women. Her essay was widely reprinted and won awards.

- In the 1890s, Emily became a leader in Federation of Women’s Clubs movement, as women realized they could have more of an impact on society if they worked together.

- Emily traveled extensively throughout her life. She was famous enough from her Brooklyn Bridge accomplishment to mix with royalty during her 1896 tour. She was presented to England’s Queen Victoria and invited to the coronation of Tsar Nicholas II of Russia.

- Emily used her skills as a construction foreman at a Montauk, Long Island camp set up to help Spanish-American War veterans in 1898. She also served as a nurse.

- Emily died on February 28, 1903. She was 59. Ironically, after all of his ill health, Wash outlived her by 23 years.

- On September 11, 2001, the Brooklyn Bridge was a lifeline for people escaping the collapse of the Twin Towers in Manhattan.

- In 2018, Brooklyn Heights named a street near the Brooklyn Bridge after Emily: Emily Warren Roebling Way. In 2020, the city decided to name a 2 acre section of the new Brooklyn Bridge Park after Emily. Emily Roebling Plaza will open in December 2021.

Want to Know More?

McCullough, David. The Great Bridge: The Epic Story of the Building of the Brooklyn Bridge (Simon & Schuster 1983).

Weigold, Marilyn E. Silent Builder: Emily Warren Roebling and the Brooklyn Bridge (Marilyn E. Weigold 2019).

Mafi, Nick. “The New York Times Spotlights the Forgotten Woman Who Built the Brooklyn Bridge” (Architectural Digest Mar. 8, 2018).

Powers, Anna. “Meet the Woman Responsible for Building the Brooklyn Bridge: Celebrating Women in Engineering” (Forbes June 23, 2019).

Serafino, Jay. “Emily Warren Roebling: The Woman Who Helped Build the Brooklyn Bridge” (Mental Floss Feb. 27, 2018).

Staff. “Emily Warren Roebling” (American Society of Civil Engineers, retrieved Mar. 2021).