Health Hero

She was a nurse whose skills were so valued by the doctors she worked alongside that they encouraged her to go to medical school, which seemed like an impossible dream in a country that was coming apart at the seams over the issue of slavery. But a scholarship from an abolitionist plus her own hard work resulted in her becoming the first Black woman doctor in the United States – graduating in the middle of the Civil War. Step back in time to 1865 and walk into the Richmond, Virginia Freedmen’s Bureau to offer medical services to freed slaves with Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler stepped off the train in Richmond, Virginia. It was 1865 and the Civil War had just ended. Rebecca, a free Black woman, volunteered to provide medical care to newly-freed African Americans in Richmond, the former capitol of the Confederacy. She knew it would be a difficult job, but she was dedicated to helping former slaves to build a new life — she considered it to be missionary work.

Rebecca wandered through town until she found the headquarters for Captain Orlando Brown, who was in charge of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands field office in Richmond (AKA the “Freedmen’s Bureau”). The Freedmen’s Bureau was established to help freedmen to become self-sufficient. It operated hospitals, schools, food kitchens, and refugee camps. It also helped freedmen to secure apprenticeships, legalize marriages, search for family members, and relocate elsewhere.

Rebecca wandered through town until she found the headquarters for Captain Orlando Brown, who was in charge of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands field office in Richmond (AKA the “Freedmen’s Bureau”). The Freedmen’s Bureau was established to help freedmen to become self-sufficient. It operated hospitals, schools, food kitchens, and refugee camps. It also helped freedmen to secure apprenticeships, legalize marriages, search for family members, and relocate elsewhere.

Richmond was ravaged from the Civil War. Much of the business district had burned to the ground when the Confederate troops retreated and abandoned the city. The damage left many residents homeless and destitute. In addition, Virginia was the largest slave state at the end of the Civil War and over 30,000 freedmen left plantations and came to Richmond to seek a new life.

Very few African Americans received medical treatment while they were enslaved. White physicians refused to treat them, and slaveholders didn’t want to pay for medical care. In addition, no one taught them about the importance of basic hygiene, prevention, or how the human body worked. And their health suffered as a result.

Rebecca was determined to help. She served patients from dawn to dusk, seven days per week. And she provided care to all patients free of charge. For many African Americans, Rebecca was the first doctor they had visited in their entire life. Some had enormous medical needs, while others only needed guidance about how to better take care of their health.

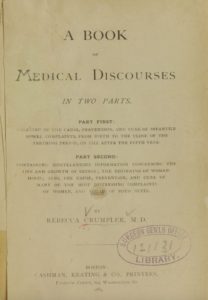

“A Book of Medical Discourses” (1883) by Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler

Rebecca was dedicated to the work she did in Richmond. But it wasn’t easy. She experienced racism and sexism every single day. White doctors ignored her, made jokes at her expense and discounted her work. In addition, it was hard for her to purchase medicine and supplies because the stores and pharmacies in Richmond refused to serve her.

Around 1870, Rebecca moved back home to Boston and opened a medical practice. She served members of the Black community of Beacon Hill. Rebecca treated everyone who came to her home on Joy Street, regardless of their ability to pay. Over the years, however, Rebecca began to specialize in the care of women and children.

Rebecca retired from medical practice around 1880. But she remained passionate about the health and welfare of African Americans in the United States. So she wrote a medical reference book. It was based on the meticulous journals she kept during her 20 years of medical practice.

Rebecca’s Book of Medical Discourses was published in 1883. It was one of the first medical reference books written by any African American (man or woman). Rebecca dedicated the book to “mothers, nurses, and all who may desire to mitigate the afflictions of the human race.” She focused on the health of women and children and emphasized the importance of nutrition and preventive medicine.

The Power of the Wand

Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler broke through societal restrictions on woman and African Americans to become pioneer in the medical field. Today, a scholarship programs helps other Black women follow their dreams. The “Rebecca Lee Crumpler Scholarship Fund” at the Boston University School of Medicine awards need-based scholarships to Black women “who aspire to become physicians.”

Her Yellow Brick Road

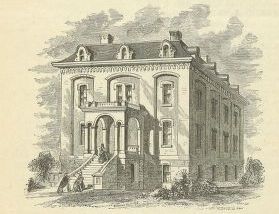

Rebecca was the only African American in her class at the New England Female Medical College. And she worked hard to be a good student and prove that she belonged there. For the first year of instruction, she had classroom instruction for 30 hours per week. Then, she had a 2-year apprenticeship with an established physician in addition to her classes. Finally, Rebecca had to complete a thesis. After three years of intense coursework, Rebecca took her final oral examinations in February, 1864.

New England Female Medical College (Wikimedia Commons)

During her oral exams, she was grilled by a panel of doctors and other medical students. There was some hesitancy to give a degree to a Black woman, but some of her teachers advocated for her — she knew her stuff and deserved it. On March 1, 1864, Rebecca became the first Black woman in the United States to earn a medical degree. She was officially a “Doctress of Medicine.”

Rebecca graduated from medical school during the middle of the Civil War. Her first job was in Boston, caring for Black Civil War veterans who were sick or injured. Most white doctors wouldn’t treat Black veterans, even though they fought for the Union. So Rebecca stepped in and cared for these heroes. But she wanted to broaden her experience. So she moved to the “British Dominion” — probably Canada — and provided medical care to poor women and children. When the Civil War ended, however, Rebecca felt compelled to return to America and help the newly-freed African Americans in the South to build new lives.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Rebecca was raised by her aunt in Pennsylvania, who had a huge influence in her life. Her aunt was a “healer” in their community — she provided medical advice but didn’t have a license. She operated a clinic out of her house and enlisted Rebecca to help her care for sick neighbors.

Rebecca was extremely bright and attended a a prestigious private school, the West-Newton English and Classical School in Massachusetts. The school was unique because it had a diverse student body — both boys and girls of all different races attended school together.

Rebecca was extremely bright and attended a a prestigious private school, the West-Newton English and Classical School in Massachusetts. The school was unique because it had a diverse student body — both boys and girls of all different races attended school together.

In 1852, Rebecca moved to Charlestown, Massachusetts and worked as a nurse. She learned on the job, since there were no formal nursing school programs back then. After eight years, Rebecca knew she was ready for more. Some of the physicians she worked with noticed her taken and suggested that she attend medical school. In fact, they insisted and provided her with a letter of recommendation.

In 1860, Rebecca was admitted to the New England Female Medical College, which was based in Boston and connected to the New England Hospital for Women and Children. Rebecca could not afford the tuition, however. Thankfully, she received a scholarship to attend medical school. The Wade Scholarship Fund was established by the Ohio abolitionist, Benjamin Wade. She was on her way to making her dreams come true!

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- Rebecca was born on February 8, 1831 in Delaware. Her parents were Absolum Davis and Matilda Webber. She was raised by her aunt in Pennsylvania.

- Rebecca attended West-Newton English and Classical School in Massachusetts as a “special student.”

- On April 19, 1852, Rebecca married Wyatt Lee, a Virginia native and former slave. He died of tuberculosis on April 18, 1863.

- Rebecca attended New England Female Medical College and graduated in 1864. She became the first Black woman in America to receive a medical degree. At the time, there were only 300 women doctors in America (out of 54,543 doctors).

- Rebecca was the only Black woman to graduate from New England Female Medical College — it closed in 1873 due to financial issues and was incorporated into the Boston University School of Medicine.

- Rebecca married Dr. Arthur Crumpler on May 24, 1865. Arthur was a former fugitive slave from Virginia. They had one child, Lizzie Sinclair Crumpler.

- In 1864, Arthur and Rebecca moved to Virginia to work for the Freedman’s Bureau.

- They returned to Boston around 1870, and Rebecca practiced medicine there for about 10 years. Their home on Joy Street is a stop on the Boston Women’s Heritage Trail.

- Rebecca and Arthur retired and moved to Hyde Park, New York in 1880.

- Rebecca published her medical book in 1883.

- Rebecca died on March 9, 1895, in Fairview, Massachusetts. She is buried at the nearby Fairview Cemetery

- Rebecca’s grave was unmarked for many years. In 2020, she finally received a gravestone. A dedication ceremony was help on on July 16, 2020 at Fairview Cemetery.

- The Rebecca Lee Pre-Health Society at Syracuse University and the Rebecca Lee Society, one of the first medical societies for Black women, were named after her.

- Boston University School of Medicine’s “Rebecca Lee Crumpler Scholarship Fund,” provides financial aid to women students of color. (https://www.bumc.bu.edu/busm/2020/10/09/rebecca-lee-crumpler-scholarship-fund-to-honor-first-black-woman-physician/)

Want to Know More?

Crumpler, Rebecca. A Book of Medical Discourses in Two Parts (Boston: Cashman, Keating and Co, 1883). (retrieved at: https://archive.org/details/67521160R.nlm.nih.gov/page/n4/mode/1up).

Bel Monte, Kathryn. African-American Heroes & Heroines : 150 true stories of African-American heroism. (Hollywood, FL: Lifetime Books, 1998).

Markel, Dr. Howard. “Celebrating Rebecca Lee Crumpler, First African American Woman Physician. PBS News Hour, March 19, 2016 (https://www.pbs.org/newshour/health/celebrating-rebecca-lee-crumpler-first-african-american-physician).

“Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler.” Changing the Face of Medicine, National Institutes of Health (https://cfmedicine.nlm.nih.gov/physicians/biography_73.html)