Culture Changer

She took a chance and said yes to an opportunity to leave her Lakota reservation and teach filmmakers about her language and culture. Her decision led to her spending months on a movie set, co-starring in the film, and standing on the stage at the Academy Awards sharing her heritage with millions of people. Jump back to 1991 and meet Doris Leader Charge…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

Doris Leader Charge was on the edge of her seat. She was in the audience at the March 25, 1991 Academy Awards. The Shrine Theater in Los Angeles was a long way from her home on the Rosebud Indian Reservation in South Dakota, where she was a Lakota Sioux language and culture teacher.

Doris was there with the cast and crew of the movie Dances With Wolves, a different kind of “Western” movie. The movie was a phenomenon because it was one of the first to tell the story of westward expansion from the Indian point of view. American audiences were treated to a full and authentic portrayal of what Lakota language and culture was like before the government forced the Lakota into reservations to make room for the soldiers and settlers who moved west after the Civil War.

Lakota people near Pine Ridge Reservation 1891 (Grabill Collection, Library of Congress)

Much of the movie was in Lakota with English subtitles. Author Michael Blake was a nominee for best Adapted Screenplay, but he wrote it in English. Doris was the one who translated his dialogue into Lakota and taught the actors how to speak it.

The presenter announced Michael as the winner, to thunderous applause. When he reached the stage, he invited Doris to join him because he wanted to talk directly to young people all over the world, and needed Doris, “who played a critical role in our film” to help him.

Doris walked to the microphone and, in a first for the Lakota people, shared their language with the theater audience, 42 million American television viewers, and millions more watching worldwide. As Michael spoke, Doris translated these words into Lakota. “My success began when I started to read books. Dreams come out of books. And the dream that came to me was to do something beneficial for as many people as I could. The miracle of “Dances With Wolves” is that it proves this kind of dream can come true. Hold on to your dreams. Don’t let anyone take them away. Never give up.”

Doris walked to the microphone and, in a first for the Lakota people, shared their language with the theater audience, 42 million American television viewers, and millions more watching worldwide. As Michael spoke, Doris translated these words into Lakota. “My success began when I started to read books. Dreams come out of books. And the dream that came to me was to do something beneficial for as many people as I could. The miracle of “Dances With Wolves” is that it proves this kind of dream can come true. Hold on to your dreams. Don’t let anyone take them away. Never give up.”

Doris was aware of the power of the moment as she spoke, reflecting later that “when I went up and picked up that Oscar for “Dances With Wolves,” I finally showed the world Indians are here and we’re here to stay.”

The Power of the Wand

In traditional Western movies, Native Americans were usually portrayed as villains or primitive savages. Doris’ work on Dancing With Wolves made it the most authentic and sympathetic portrayal of Native American life that had ever been shared with an American audience. The Sioux community was appreciative, stating that Dances With Wolves was a “fair and genuine treatment of their heritage” and “one of the few honest portrayals of Native Americans losing their culture and identity to the white man.” Doris hoped that the film would build confidence among the young people on her reservation.

Doris’ legacy of sharing and building understanding of Native American life through popular culture continues today. Check out storyteller and activist Sarah Eagle Heart, who won an Emmy award for her work on the virtual reality animated short film Crow, The Legend. The film tells the Native American origin story of the crow, how it sacrificed its own glory to aid the community, and how it became a cultural symbol of good luck and wisdom. Eagle Heart worked with filmmakers on the characters and storylines, was a liaison with tribal communities, and was cast in the movie (alongside John Legend and Oprah) as the voice of Luna.

Her Yellow Brick Road

Doris was teaching Lakota Studies at Sinte Gleska Tribal College on the Rosebud Reservation when she got a call from the Dances With Wolves filmmakers. She said “I was really surprised when a movie producer called and asked me to translate a script because I really didn’t know what a script was.” The nearest movie theater was 50 miles away from the two bedroom house she shared with her husband Fred and 6 kids. Right after they moved in seven years earlier, somebody broke into it, broke several windows, and punched holes in the walls. They were still saving money for repairs.

Lakota language textbook (lakotalanguageproject.org)

Doris decided to give it a try and told the producers to send her the script. Three weeks later she sent back a Lakota language version of the entire screenplay. Doris also sent the producers something they hadn’t known they needed: an audio tape she made of each character’s lines in English and Lakota so the actors could learn to speak their lines accurately. “Lakota is a very difficult language with so many strange sounds,” she explained. “We had to first translate the script the way we would speak it, then go back and simplify the dialogue using fewer, easier words with similar meanings.”

Since teaching actors to speak authentic Lakota was a much bigger challenge than the filmmakers initially realized, they asked Doris to travel to Rapid City to be the actors’ dialogue coach during rehearsals. Doris spent 3 weeks teaching the actors their Lakota lines. Every actor needed individualized lessons, because of the differences in how their characters would speak Lakota.

For example, one character was a soldier who went west after the Civil War. He was a white man who met the Lakota as an adult, so he would speak like a beginner. Another character was a white woman who had been raised by the Lakota since she was a child, so she would be fluent, but with a different accent than those playing the native Lakota. Doris set up a classroom in the hotel and made the actors repeat their lines until they were perfect

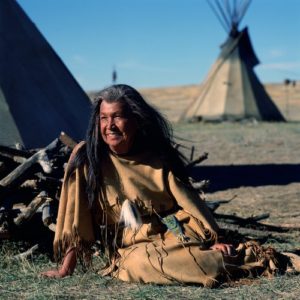

Doris as Pretty Shield in Dances with Wolves (Still Image from Orion Pictures via EPIX)

Doris became so important to the authentic portrayal of Lakota life that the filmmakers made her an offer they assumed she couldn’t refuse: the chance to be in the movie. They asked her to play Pretty Shield, the wife of Lakota Chief Ten Bears. To their surprise, Doris said no. They asked her again. She said no again. Finally, one of them invited Doris on a long walk, and asked her why she wouldn’t stay. The reason: Doris had used her allotted vacation from Sinte Gleska to tutor the cast and her time was up. She told him that “your film will only show for a few months, but I’ll need this job long after that.”

The filmmakers asked if she would stay if Sinte Gleska agreed to hold her job until filming was over. Doris said yes, Sinte Gleska said yes, and Doris spent the next 6 months on set as a dialogue coach and actress. She would take actors aside between scenes and during meals to tweak their Lakota pronunciation. Some days they worked from 8am to midnight.

Brains, Heart & Courage

When the Lakota were moved onto reservations after the Civil War, the government put such a priority on assimilation that very few people learned the Lakota language. Doris, who grew up on the Rosebud Reservation, was an exception. She was raised by her grandmother, who spoke only Lakota to her. Doris didn’t learn English until she was 13 and sent to the St. Mary’s School for Girls. As an adult, she was one of the only members of her tribe fully fluent in Lakota.

Like most Rosebud residents, her family was poor. Most reservations are on remote lands without much infrastructure, making it hard for residents to find a job nearby or go to high school or college. Like most Rosebud teens, Doris had to help support her family. She left St. Mary’s when she was 14 to get a job.

Doris got married at 16. By age 21, she had three kids with one on the way when her husband died of a heart attack. She spent the next 6 years as a single mom working multiple jobs, including as a waitress, cook, and nurse’s aide. When Doris was 27, she married a fellow Lakota named Fred Leader Charge. Doris and Fred spent the next 12 years moving around, working any jobs they could find to support their family, now 4 sons and 2 daughters.

Doris and Fred wanted more stability for their family, so they returned to Rosebud so Fred could enroll at Sinte Gleska. Fred received a private grant for part of his tuition, and Doris paid for the remainder with her nurse’s aide salary. When Sinte Gleska decided to build a Lakota studies program to revive the Lakota language, administrators invited Doris to teach classes in Lakota language and tradition. Doris amazed everyone with her ability to teach Lakota and became “the expert” who taught other teachers how to teach Lakota.

Glinda’s Gallery

Visit Doris’ digital scrapbook on Pinterest: https://www.pinterest.com/theglindafactor/doris-leader-charge/

Just the Facts

- Doris Whiteface was born May 4, 1930, on the Rosebud Indian Reservation in South Dakota.

- Doris earned a degree in elementary education from Sinte Gleska when she was 54. Sinte Gleska was a four year private American Indian tribal college. Tribal colleges were often the only option for reservation residents. They honor Indian heritage by teaching classes about tribal culture and providing Indian perspective on core subjects like social studies and science.

- The Lakota language is unique in that men and women speak it slightly differently. Doris and the filmmakers decided that was too complicated to teach in a short time, so all characters in the movie speak in the woman’s version.

- Dances with Wolves won seven Academy Awards out of its 12 nominations. It won Best Picture, Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Original Music Score, Best Cinematography, Best Film Editing, Best Sound

- Once filming finished, Doris went back to her life at Rosebud and Sinte Gleska with the $23,800 she earned for her translating, teaching, and acting. This was more than Doris’ annual $17,000 salary. Doris used her earnings to repair her house and buy a new stove, refrigerator, washer and dryer.

- Doris taught at Sinte Gleska for 28 years, until her death on February 20, 2001.

Want to Know More?

Giago, Tim. “When Doris Leader Charge Spoke, Kevin Costner Listened.” Huffington Post, 2 June 2012.

Miller, Steve. “Lakota Teacher Leader Charge Dies.” Rapid City Journal, 19 Feb. 2001

Ross, Scott. “Dances with Wolves — Natives Portrayed Honestly and Sympathetically.” Windspeaker Publication, Volume 8, Issue 19 (1990)

Thigpen, David. “Kevin Costner Said the Words, but Doris Leader Charge Made the Dances Dialogue Truly Sioux.” People, 21 Jan. 1991