Awesome Athlete

She was a girl from New York City who loved art, acting, and athletics. And when she discovered that figure skating was a way to combine those passions, she never looked back. Her pursuit of her dreams took her around the world, but she made Olympic history in her own backyard. Step back in time to the 1932 Winter Olympics in Lake Placid, New York and meet Beatrix Loughran…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

While waiting for her turn on the ice at the 1932 Winter Olympic Games in Lake Placid, New York, Beatrix Loughran took her last opportunity to adjust her costume. She was wearing a white satin skating dress trimmed with ermine fur. Her black stockings and gloves provided a dramatic contrast. Her skating partner, Sherwin Badger, looked handsome in his dark suit. This was their second Olympics together. Their first had been the 1928 Winter Games in St. Moritz, Switzerland.

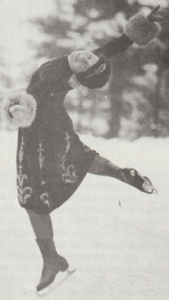

Bea in her daring knee length skirt. (Skating Magazine)

Those 1928 Games had been a whirlwind for Bea. Bea had a full schedule – she was competing in both singles and pairs. Fortunately, her Atlantic crossing aboard the S.S. Majestic had been uneventful, so she was able to relax and spend time walking through her routines. She also did some mental preparation for the unpredictable and difficult outdoor ice conditions she now knew to expect after her experience at the 1924 Winter Games in Chamonix, France. As always with natural ice, there were areas skaters had to be avoid because they were bumpy or too thin. Getting a skate caught in one of them was a recipe for a fall. The St. Mortiz officials marked the bad ice with flags.

Bea was ready for the challenge of adapting her routine to stay on the good ice. For her singles routine, Bea decided that she wanted a costume easier to skate in than the traditional long dress, so she took to the ice in a knee-length skirt. Her hope was that her shorter skirt would make her more mobile and able to navigate the irregular ice. It did, and Bea’s free skate scored more points than her two closest competitors.

However, when it came to the judges’ comparative rankings, only one judge placed her first. The scoring was so confusing that some American sportswriters initially reported that she had won the Gold when she had actually won the Bronze. She was proud to head home with the second medal of her Olympic career. Meanwhile, some in the conservative skating world were more focused on her shorter skirt than her performance. She faced many questions afterwards about why she chose such a revealing and risqué costume. She told them the truth: “I just want to be comfortable.”

Bea and Sherwin performing one of their signature skills

Bea had hoped for another medal in the pairs event, although she knew it would be a longshot, since she and Sherwin were a relatively new pairing making their Olympic debut. They were well suited – both were quick skaters with a bouncy, staccato style. The two of them were excited to show off the difficult spin move they had designed, where their right hands were on each other’s waists with their left hands held together over their heads. It was technically difficult, beautiful to watch, and created a dramatic effect. And while they just missed a medal, finishing fourth, they captured the world’s attention as a pair to watch.

After the 1928 Games, Bea retired from singles competition to focus on a winning a medal at the 1932 Games with Sherwin. Their Olympic experience provided a strong foundation for their partnership. They spent hours working on new moves and innovating their routine and their hard work began paying off quickly. They won the U.S. Pairs Championship in 1930, 1931, and 1932. They proved themselves on the world stage by medaling at the 1930 and 1932 World Championships.

And now here they were, in 1932, at an Olympics Winter Games again. And again, they were underdogs. The French pair of Andree Joly and Pierre Brunet won Gold in 1928 and were the overwhelming favorites to repeat at Lake Placid.

And now here they were, in 1932, at an Olympics Winter Games again. And again, they were underdogs. The French pair of Andree Joly and Pierre Brunet won Gold in 1928 and were the overwhelming favorites to repeat at Lake Placid.

It was time for Bea and Sherwin to skate out to center ice. There were 5000 people in the stands, eagerly awaiting their first sight of the hometown duo. Bea loved hearing the cheers, but reminded herself to keep her focus on the routine. She did her best to harness the crowd’s energy without getting distracted by it. That was easier said than done, as the fans were vocal throughout their performance. The cheers got louder and more excited when the music sped up and fell into an intense silence or oohs and aahs when the music slowed down.

Bea and Sherwin skated perfectly – not a single mistake. The favorite French pair had some missteps, but their routine had more difficult lifts. All four skaters knew it could go either way, and sat on pins and needles waiting for the judge’s decision. Each team got two scores: a point total based on how well they executed their routine and a ranking where each judge placed them compared to other teams. Bea and Sherwin earned the most points, but the judges gave their French rivals more first place rankings.

Bea and Sherwin skated perfectly – not a single mistake. The favorite French pair had some missteps, but their routine had more difficult lifts. All four skaters knew it could go either way, and sat on pins and needles waiting for the judge’s decision. Each team got two scores: a point total based on how well they executed their routine and a ranking where each judge placed them compared to other teams. Bea and Sherwin earned the most points, but the judges gave their French rivals more first place rankings.

Although they narrowly missed out on the Gold, Bea and Sherwin were very proud of their Silver medal. They were the first American pair to medal at the Olympics, and Bea became the first (and still only) American figure skater to win three Olympic medals.

The Power of the Wand

Bea was the first American woman to win a Winter Olympics medal, and is the only American to have won three Olympic medals in figure skating (two silver, one bronze). Bea set the tone for decades of Olympic success by American women figure skaters. The 2022 Games has another strong U.S. team led by 2022 U.S. Women’s Champion Mariah Bell, who was the oldest to win the title since Bea did in 1927. Mariah is joined by 22 year old Karen Chen and 16 year old Alysa Liu.

Her Yellow Brick Road

In 1919, Bea sought out a figure skating coach who could help her develop the skills and confidence she needed to enter skating competitions on a bigger stage. It was expensive, so she worked as a switchboard operator to pay for them. Every chance she had, she headed to the St. Nicolas Rink in Manhattan to train for both components of an official skating competition – figures and the free skate. Figures are the shapes skaters trace in the ice (like figure 8s) which judges evaluate for edge, roundness, and precision. The free skate is a routine set to music that must incorporate certain skills. Final scoring also had two components – 1) points earned from figures and the free skate and 2) the judge’s ranking of each skater in the competition compared to each other, i.e. who the judge believed should place 1st, 2nd, 3rd ….

Bea doing figures – her specialty. (McGill University Library)

One of Bea’s first major skating competitions was the 1920 U.S. Junior Women’s Championship at the Iceland Rink in New York City. She finished 3rd – and only missed second place because her figures scores were so low. Bea took that to heart and started devoting even more of her practice time to perfecting her figures, now believing were the foundation for excellent skating. Her strategy paid off the following year, when she won the 1921 Junior Women’s Championship in Philadelphia. Her figures were excellent, her free skate earned her high points, and four of five judges ranked her in first place.

Bea decided to enter three Senior Women’s competitions in 1922. She won the Metro Championships of NY, placing first in figures and the free skate. She won in Lake Placid, where her figures scores put her on top. Her biggest stage was her first U.S. Women’s Championship. Teresa Weld Blanchard, the top skater in the country, was the overwhelming favorite. But Bea gave Teresa a scare by nearly matching her scores in figures. Both women had impressive free skate routines. Teresa prevailed, but not by nearly as much of a margin as she had expected. With her second place finish, Bea established herself as a skater to watch. Her signature style of “verve and dash” engaged judges and audiences alike. Bea took that energy back to practice, decided to add ice dancing to her repertoire, and won the U.S. Waltzing title with a partner.

Bea (middle) and her fellow American teammates Teresa Weld Blanchard (L) and Maribel Vinson (R)(Skating Magazine)

Bea arrived at the 1923 U.S. Championships excited to challenge Teresa again. This time Bea came even closer to beating her– two of the five judges picked Bea first in figures, and one judge voted to give her the title of U.S. champion. Bea followed up with a second place at the North American Championships. She now had the attention of the International Skating Union of America, which offered her a spot on the U.S. Team for the 1924 Winter Olympics. Bea accepted, and started getting ready for her trip across the Atlantic to Chamonix, a mountain town at the foot of Mount Blanc in the French Alps. The figure skaters and speed skaters left for France on January 2. They spent the next two weeks enjoying what the ship had to offer – although it was a cold and windy time to be on the ocean which made it difficult to stay in shape for competition.

Bea was happy to put her feet on solid ground again, and while she was not expected to medal, Bea believed in herself and was excited to skate against the favorite, Austria’s Herma Szabo. There were no indoor ice arenas at these games – all skating competitions took place on frozen lakes. The first part of the competition was figures. Bea did very well and went into the free skate with the lead. The weather conditions at the free skate were difficult – the ice was bumpy and the winds were howling. Bea struggled with her spins, which were usually her strong suit. But she kept moving through her program, and at the end, finished in second place with the Silver medal. All seven judges placed her second, twenty points per judge behind the Austrian winner. Teresa Blanchard, Bea’s friend, rival, and the American favorite, finished fourth.

Bea (r) with the other medalists at the 1924 Games: Herma Plank-Szabo (l) and Ethel Muckelt (m)

Bea was the first American woman to win a Winter Olympics medal in any sport or event, and the American media went wild celebrating Bea’s success. The country eagerly awaited her return to New York. After a stop in Norway for the World Championship, where Bea proved her success wasn’t a fluke by finishing third, the team headed home. When her ship anchored in the harbor, a police tugboat came to bring her to shore accompanied by a brass band! She was featured in several news stories and in Skating Magazine. Bea appreciated the attention but also made sure to highlight how impressed she was with one of her competitors – 11 year old Sonja Heine., who she predicted would become a skating legend (she was right!).

Bea celebrating her Olympic success (Library of Congress)

Bea continued to develop as a singles skater. She won the U.S. Women’s Championship in 1925, finally dethroning Teresa Blanchard, who had been the reigning champion for 7 years. Bea again dominated in figures, building a 20 point lead she hung onto after the free skate. She won the North American Championship in Boston later that year and defended both titles in 1926 and 1927. Bea also continued ice dancing and discovered pairs skating, which she loved because skating with a partner gave her twice as many events to enter.

Bea started looking for the right partner. She won the Skating Club of New York’s Waltz competition with Ferrier Martin and finished second with Raymond Harvey at the U.S. Pairs Championships. And then she met a Boston skater named Sherwin Badger while he was in town on business. The two of them went to the rink together and decided to give a partnership a try.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Bea’s father died when she was a baby. Her mom had to move from their house in a New York suburb to the Bronx in New York City. She worked multiple jobs to raise Bea and her two older sisters – Margaret and Alice – as a single mom. But she still made sure the girls had plenty of opportunities to explore different activities.

Bea loved art and acting. She was in the cast of shows at the Provincetown Theater in . She was always ready for a challenge and willing to take on whatever role she was given – she even played a male part in the play “The Hand of the Potter.” But she also loved sports and being active. She learned to ski in the mountains around Lake Placid, New York. She also learned to dive and competed for New York’s Women’s Swimming Association.

Bea eventually found an activity that combined her passion for artistry and athletics when she discovered figure skating. She started spending as much time as she could at the Skating Club of New York.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- Beatrix (“Bea”) Suzetta Loughran was born on June 30, 1900 in Mount Vernon, New York.

- Bea lived in the famous Barbizon Hotel for Women in the late 1920s. Many of Manhattan’s single, independent women made their homes there because it was a socially acceptable and safe place for a woman to be on her own in a time when most either lived with their parents or husband – there was a curfew and strict “no men allowed” policy.

- In addition to skating, Bea was an accomplished golfer. She played in golf tournaments during the summer, representing the Coldstream Club. She started racking up wins and getting mentioned for her golfing prowess in the New York Times. She won the Westchester-Fairfield Women’s Golf Association Invitational in 1930.

- After she hung up her skates, Bea coached her niece Audrey Peppe. Audrey placed third at the U.S. Championships in 1936 and second in 1937 and 1938. When Audrey made the U.S. Team for the 1936 Olympics in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Bea went with her. Audrey was selected for the 1940 Games as well, but they were cancelled because of World War II.

- After she retired from competition, Bea continued to perform in skating exhibitions and served as a figure skating judge. She was one of 10 American judges approved by the U.S. Figure Skating Association to judge at the World Championship level.

- Bea married Raymond Harvey, one of her former skating partners, on February 28, 1942. The two of them lived abroad for years in Mexico and Switzerland.

- Bea died on December 7, 1975 at age 75.

- Bea was inducted into the U.S. Figure Skating Hall of Fame in 1997, 22 years after her death.

Want to Know More?

Staff. “Biography: Beatrix Loughran” (Olympics.com)

Stevens, Ryan. “Barbizon Queen: The Beatrix Loughran Story” (Skateguard Sept. 3, 2019)

Staff. “United States Figure Skating Association, p.18-20” (The Sportswoman Nov. 1926).