Passionate Patriot

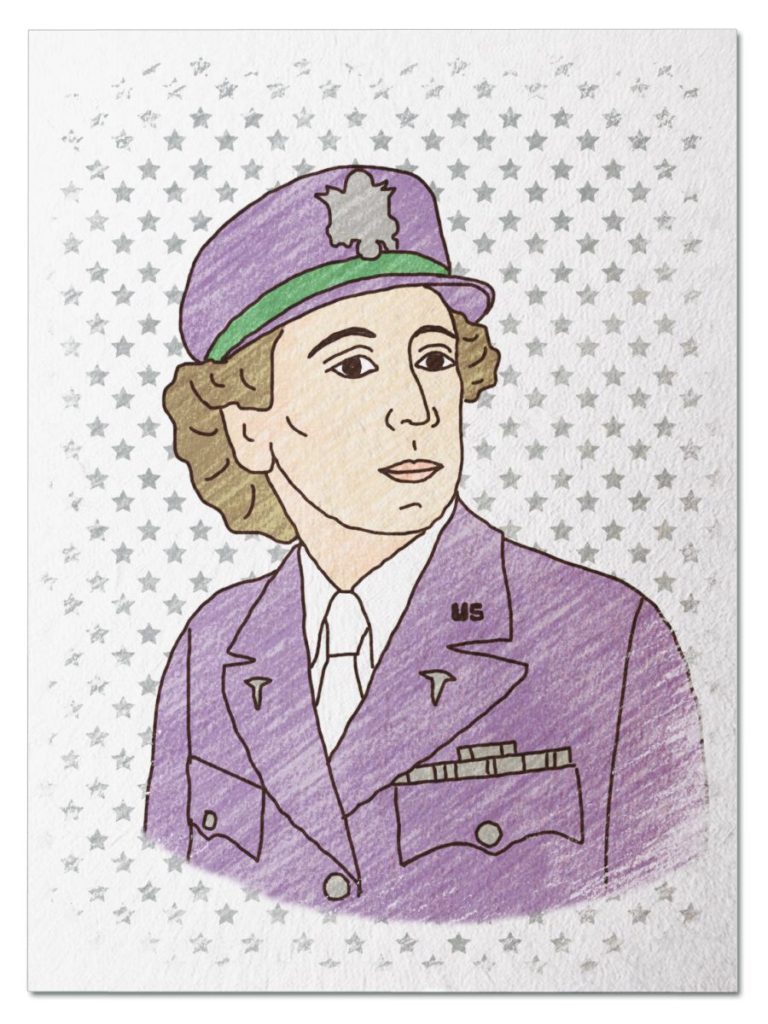

She was the new Chief Nurse at a quiet Army hospital in Honolulu, located next to the Naval base at Pearl Harbor. When she arrived at work on the morning of December 7, 1941, she had no idea that the entire world was about to turn upside down. Her bravery and skill that day earned her the first Purple Heart awarded to a woman in service. Travel back in time to the day that will live in infamy and meet Annie Fox…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

Annie Fox, or 1st Lieutenant Fox, as she was known in the Army, arrived at Station Hospital on Hickam Field in November 1941 to take the position of Chief Nurse. Hickam Field was the Army’s primary airfield and bomber base in Honolulu, Hawaii. It was located right next to Pearl Harbor, the U.S. Navy’s main base in the Pacific.

The Army Nurse Corps had shrunk in size since The Great War – there were only 1000 nurses total, with 82 of them stationed at the 3 Army hospitals in Hawaii. Station Hospital had 30 beds and was staffed with 6 nurses. Annie loved her job and the younger nurses who reported to her. Her affection was returned. It was a happy group enjoying their work and the beauty of the Hawaian islands in their off-duty time.

Annie woke up on the morning of December 7, 1941 expecting it to be just another day at work in paradise. She had no idea that a fleet of Japanese airplanes was heading their way for a surprise attack on the United States. At 7:48am, the first bombs dropped and Annie’s world changed.

Annie woke up on the morning of December 7, 1941 expecting it to be just another day at work in paradise. She had no idea that a fleet of Japanese airplanes was heading their way for a surprise attack on the United States. At 7:48am, the first bombs dropped and Annie’s world changed.

It was like nothing Annie had ever experienced before – and she had served near the front lines in The Great War and had been a military nurse for over 20 years. Now she found herself in the middle of a battle. The Japanese airplanes attacking Pearl Harbor were coming so close to the ground to drop their bombs that Annie and her colleagues could see the pilots from the hospital windows. Explosion after explosion shook the building. The air outside filled with black, thick smoke and the smell of burning fuel. Soon, once the U.S. scrambled to mount a defense, the sounds of machine guns and anti-aircraft artillery joined the already disturbing symphony of war.

Annie didn’t have much time to plan, As the bombs exploded outside, she mobilized her nursing staff to prepare for the coming onslaught of the injured. Amazingly, many of the wives of military personnel didn’t hide in their homes, but instead arrived at the hospital asking how they would be of help. Annie put them to work making dressings for wounds and shadowing nurses to help with whatever needed doing.

Annie did her best to keep her team focused on the patients in front of them instead of their own fear. This wasn’t an easy task, especially when 2 bombs came dangerously close to destroying the hospital itself. One of them left a 30 foot crater just outside the doors. Annie made sure each nurse had a gas mask and helmet to wear to protect them as much as possible as they worked feverishly to stabilize the wounded.

Annie also relied on the triage skills she had learned treating the combat wounded in The Great War. She instructed her nurses in how to assess who to treat first, just like her superiors 20+ years before had taught her. They welcomed hundreds of patients, most of whom had been injured by shrapnel from bombs and flying debris. The nurses moved quickly to sterilize and wrap open wounds, and to give patients who didn’t need immediate surgery enough pain medication to stabilize them for a transfer to a bigger hospital. Annie herself spent much of her time in the operating room, using the anesthesia skills she had acquired in her years of Army nursing to help the surgeons treat the most seriously wounded as quickly as possible.

The Power of the Wand

Annie was the first woman awarded the Purple Heart, on October 26, 1942. Although most recipients of the award were wounded in combat, it was occasionally given to honor a “singularly meritorious act of extraordinary fidelity or essential service.”

The citation read in part: “During the attack, Lt. Fox in an exemplary manner, performed her duties as head nurse of the Station Hospital. In addition, she administered anesthesia to patients during the heaviest part of the bombardment, assisted in dressing the wounded, taught civilian nurses to make and wrap dressings and worked ceaselessly with coolness and efficiency. Her fine example of calmness, courage, and leadership was of great benefit to the morale of all with whom she came in contact.”

The citation read in part: “During the attack, Lt. Fox in an exemplary manner, performed her duties as head nurse of the Station Hospital. In addition, she administered anesthesia to patients during the heaviest part of the bombardment, assisted in dressing the wounded, taught civilian nurses to make and wrap dressings and worked ceaselessly with coolness and efficiency. Her fine example of calmness, courage, and leadership was of great benefit to the morale of all with whom she came in contact.”

Shortly afterward, the Army changed the Purple Heart criteria to limit it to those who had been wounded by enemy forces. Two years later, on October 6, 1944, she was awarded the Bronze Star to replace her Purple Heart.

Annie’s legacy of bravery and service in medicine lives on today. The Walter Reed Bethesda Hospital named one of its facility dogs after Annie. On March 13, 2018, the Chief of the U.S. Army Nurse Corps promoted Annie the dog to an Army Captain.

Her Yellow Brick Road

After Annie moved to the United States from Canada, she embraced the opportunity to serve her adopted country. Congress had voted to enter the Great War raging in Europe in April 1917, in large part because Germany wouldn’t stop attacking American passenger and merchant ships in the Atlantic. President Wilson asked Congress for a resolution supporting what he hoped would be “a war to end all wars.” The goal: “the world must be made safe for democracy.”

Where there was war, the Army needed medical personnel to tend to the soldiers. In addition to its Army doctors and medics (all men), the Army established its Nurse Corps in 1901. The nurses were considered part of the Army but didn’t have a defined status. The nurses weren’t assigned status or rank like the commissioned officers or enlisted personnel were. They also didn’t go through basic training.

When the United States entered the Great War, the Nurse Corps included only 403 active duty nurses with 170 reserves. Six months afterwards, the numbers had grown to 1100 nurses in 9 base hospitals. The need was great because they while the Army formula for staffing war hospitals – 1 nurse per 10 beds – hadn’t changed since the American Revolution, the nature of war had changed dramatically. Modern weapons like automatic rifles and chemical weapons inflicted so much damage that the Army quickly realized it needed to make a great efforts to recruit more nurses.

By mid 1918, the Corps had grown to 2000 regular nurses and 10,186 reserves serving at 198 stations worldwide. Annie was one of the nurses who applied to join the Corps during this time. She went through a rigorous process vetting her skill and character. The women would only be sent overseas if they agreed to go. Annie told them she was willing. She deployed to Europe that summer.

Annie often worked 14-18 hour shifts day after day for weeks. She quickly adjusted to the difficult circumstances because she didn’t have time to do anything else. One of the biggest adjustments was learning how to triage as an army nurse instead of a civilian one. In the Army, the first priority was not necessarily the most critical patient, but the one who had the greatest chance of survival. The main job of Army doctors and nurse were to keep the Army strong by returning soldiers into the battlefield as soon as possible. When an injured soldier arrived, her first job was to cut off his uniform, typically filthy from the trenches. She then would clean him up so the doctors could assess his condition.

Annie became an expert in battlefield nursing. The Army initially intended to have the nurses work away from the front lines for their own safety. But the injuries soldiers suffered required immediate attention from surgical and gas treatment teams, which included nurses. There were so many patients, and so few doctors and nurses, that those who were there had to learn how to handle anything that may come their way.

Annie became an expert in battlefield nursing. The Army initially intended to have the nurses work away from the front lines for their own safety. But the injuries soldiers suffered required immediate attention from surgical and gas treatment teams, which included nurses. There were so many patients, and so few doctors and nurses, that those who were there had to learn how to handle anything that may come their way.

Annie learned how to clean wounds, a critical life-saving skill, as getting an infection like tetanus or gangrene from trench mud was a primary danger. She learned how to pick out shrapnel and clean wounds by either packing them with salt and iodine or running an antiseptic solution through them with IV bags and tubes. She learned how to treat soldiers whose lungs had been severely damaged from mustard gas. She learned how to do blood transfusions, which were a new method of stabilizing patients. And she learned how to administer anesthesia for surgical patients.

Not long after Annie joined the Corps, the Army decided to make nurses a more official part of the military. Nurses were given service chevrons like officers and enlisted men to wear on their uniforms. They also were now eligible for officer rank as a lieutenant, captain, or major. Although the war finally ended on November 11, 1918, the needs of the injured soldiers continued. Annie’s war deployment didn’t end until Summer 1920.

Annie stayed in the Corps, spending the next 20 years stationed at various bases around the world, including Fort Sam Houston in Texas, Fort Mason San Diego in California, and then to the Philippines at Camp John Hay in Benguet and then Manilla.

In May 1940, Annie received a new assignment – to Honolulu, Hawaii. She was excited to be closer to the U.S. mainland but still live in a tropical paradise. She was granted an exam for promotion to Chief Nurse on August 1, 1941. She was successful, earned the rank of 1st Lieutenant, and was transferred to Hickam Field in November 1941.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Annie was born and raised in E. Pubnico, a small Canadian village in Nova Scotia, Canada. Medicine was a family tradition, as her dad, Charles, was a doctor in town. Annie and her six siblings Mary, Leslie, Maria, Charles, Dorothy, Lyle and Eunice. The Fox children grew up with his stories about work at the dinner table. Annie decided to follow in his footsteps and explore a career as a nurse.

After her mom, Deidamia (whose nickname was Annie), died in May 1917, her grief prompted her to seek out a new path. She moved to the United States and decided to apply to the Army Nurse Corps.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- Annie was born on August 4, 1893 in Nova Scotia, Canada.

- The Army Nurse Corps grew from 1000 at the start of World War II to more than 59,000 by its end.

- Annie was eventually promoted to Major, and that was her rank when she retired from the Army on December 31, 1945, after World War II ended.

- Annie spent her retirement years in northern California. She died on January 20, 1987 at age 93 and is buried in the San Francisco National Cemetery.

Want to Know More?

Staff. “Major Annie Gayton Fox: United States Army Nurse Corps” (Wartime Heritage Foundation).

Staff. “Honoring the American Heroine: The Story of Lt. Annie G. Fox” (Purple Heart Foundation Mar. 15, 2017).

Staff. “The Bravery of Army Nurse Annie G. Fox at Pearl Harbor” (National Women’s History Museum Dec. 6, 2016).

“Lt. Annie G. Fox: First Purple Heart” (Geni.com).