Amazing Artist

She was taken from her home as a child and forced onto a ship bound for the American Colonies. After being purchased as a house slave, her owners took note of her intelligence. She was a teenager when she mastered multiple languages and began to write poetry. Her poems, eventually published in England, brought her fame throughout the world. After being granted her freedom, she used her pen to advocate for the abolition of slavery throughout the Colonies. Step back to the middle of the Revolutionary War and meet Phillis Wheatley …

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

Phillis Wheatley stared at the April 2, 1776 edition of the Pennsylvania Magazine. There, in black and white, was the letter and poem she had sent to General George Washington back in October. It stated, “The following Letter and Verses, were written by the famous Phillis Wheatley, the African Poetess, and presented to his Excellency Gen. Washington…”

Her poem, Columbia, was an ode to the new nation of America. She supported the patriots in the Revolutionary War and praised the appointment of George Washington as commander of the Continental Army. So she sent him a copy of Columbia. And he responded to her letter a few months later, on February 28, 1776. In it, he thanked her for the “elegant Lines you enclosed, however undeserving I may be…” Then, he invited her to visit his headquarters in Cambridge, he “shall be happy to see a person so favored by the Muses.”

Her poem, Columbia, was an ode to the new nation of America. She supported the patriots in the Revolutionary War and praised the appointment of George Washington as commander of the Continental Army. So she sent him a copy of Columbia. And he responded to her letter a few months later, on February 28, 1776. In it, he thanked her for the “elegant Lines you enclosed, however undeserving I may be…” Then, he invited her to visit his headquarters in Cambridge, he “shall be happy to see a person so favored by the Muses.”

It’s thought that Phillis took General Washington up on his invitation and visited his headquarters in March, 1776. Legend says that she took the opportunity to lament the hypocrisy of creating a new nation based on equality, while patriots such as Washington also enslaved African Americans. She believed that slavery would prevent the young nation from achieving true greatness. So she encouraged General Washington to expand his idea of “Liberty” to include everyone.

Phillis may have worried that her outspoken nature offended General Washington. But her letter and poem that was published in the Pennsylvania Magazine could only have come from General Washington himself. It was was a high honor indeed. And evidence that he wasn’t offended by her abolitionist ideals.

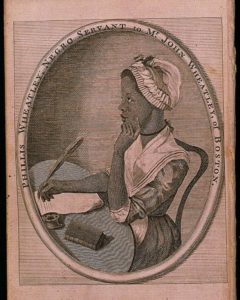

Phillis Wheatley, National Park Service

By the time she corresponded with General Washington, Phillis was a well-known, published poet. Her first book of poems was published in 1773 in England, which made her one of the best known poets in the Colonies and the first African American to be published.

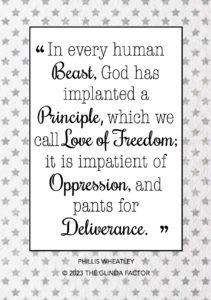

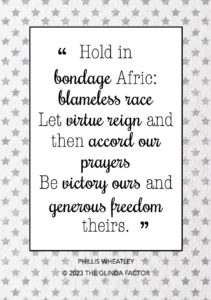

Much of Phillis’ work was influenced by African traditions and religious ideals. She wrote many elegies — poems that honor someone who has died. Over time, however, her work took a more political tone. She commented on political issues of the day, such as the Stamp Act and the Boston Massacre. In addition, she expressed her outrage against slavery in the context of Christianity. She used allusions to Biblical stories as an argument against slavery, as well as outright comparisons to the enslavement of Jews by the Egyptians.

Phillis went on to write many more poems, but published very few of them. She tried to publish a second book of poems and placed advertisements for subscriptions throughout Boston. She planned to include 33 poems and 13 letters. But it was never published. And most of the poems are lost

The Power of the Wand

Phillis Wheatley the second American woman and the first African American to become a published author, as well as one of the best known poets in America until the 1800s. She was also an abolitionist and an inspiration for the young anti-slavery movement.

Her Yellow Brick Road

In 1770, Phillis wrote a poem that changed the course of her life. It was an elegy for Reverend George Wakefield, a preacher who was famous throughout the American Colonies. Phillis wrote the poem in Whitefield’s honor after his death on September 29, 1770. An Elegiac Poem, on the Death of that Celebrated Divine, and Eminent Servant of Jesus Christ, the Reverend and Learned George Wakefield was published as a broadside and pamphlet in Boston, Philadelphia, and New York. It was also published in London, as part of the coverage of Whitefield’s funeral.

Around that same time, Phillis and Susannah sought to have her poems published as a book. They didn’t have much luck in the American Colonies, however — no one was ready to support the writing of an African slave. So they decided to try London.

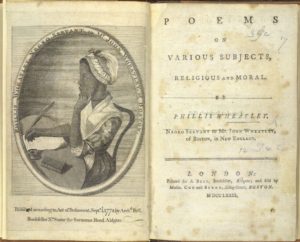

Phillis Wheatley’s Book of Poems

Susannah sent a sample of Phillis’ poems to her friend, Selina Hastings, the Countess of Huntingdon. Selina was known as devoted Evangelical Christian and abolitionist, as well as a follower of George Whitefield. Selena was impressed with Phillis’s talent. So she invited Phillis to London and offered to help publish her book of poems. She agreed to financially support the publication and asked her bookseller, Archibald Ball, to help with the specifics of publication and distribution.

Before she left, however, Phillis needed to get attestations from members of the Boston community that the poems were indeed written by her own hand. Selena anticipated that some may doubt that a young Black girl could create such elegant poetry on her own. Eighteen prominent Boston men interrogated her to determine whether she had the knowledge and ability to write her poems, then signed the attestation in her favor, including Thomas Hutchinson, the Governor of Massachusetts; John Hancock; James Bowdoin; and Dr Benjamin Rush (a signer of the Declaration of Independence).

Phillis boarded a ship for London on May 8, 1771. She was accompanied by John and Susannah’s son, Nathaniel Wheatley. Phillis found more freedom in London than she had in the Colonies — she wasn’t considered a slave while on English soil. Instead, English law considered her a free woman. She found acceptance as an artist, a woman, and an African American. She was also welcomed by the academic community in London, including Benjamin Franklin.

Phillis boarded a ship for London on May 8, 1771. She was accompanied by John and Susannah’s son, Nathaniel Wheatley. Phillis found more freedom in London than she had in the Colonies — she wasn’t considered a slave while on English soil. Instead, English law considered her a free woman. She found acceptance as an artist, a woman, and an African American. She was also welcomed by the academic community in London, including Benjamin Franklin.

Phillis finally achieved her dream while in England. Her book, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, was published in London in late 1773. It included a collection of 28 poems, as well as the attestations of Boston men in a forward to show it was authentic. Phillis was suddenly the most famous poet in the British Empire.

Abolitionists throughout the British Empire, including the American Colonies, took notice — Phillis Wheatley, international sensation, was not a free woman. They criticized the Wheatley family for keeping Phillis in slavery and called on them to grant Phillis her freedom. Some claimed that she was free so long as she didn’t return to the Colonies — an English court ruling the previous year held that an enslaved person brought to England from the Colonies could not be forced to return as a slave.

But then, Phillis received word that Susanna Wheatley was ill. She voluntarily returned to Boston as quickly as possible and tended to Susannah until she died on March 3, 1774. A few months before Susannah died, however, Phillis was finally granted her freedom.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Phillis was born and raised in Senegal, West Africa until she was captured by slave traders in 1760. It is unknown if the rest of her family was captured as well. She was brought to Boston on the slave ship, Phillis, with a shipment of “refugee slaves” — Africans who weren’t capable of the manual labor required in the Southern colonies.

After arriving in August, 1761, Phillis was taken to the city’s slave market to be sold. The captain thought that she was about 7 or 8 years old, based on her permanent teeth. She was very sick and malnourished, with only a piece of fabric wrapped around her for clothing. In fact, the captain was so convinced that she would die soon that he asked a low price for her.

Phillis Wheatley Statue, Boston Women’s Memorial

John Wheatley was a tailor in Boston and headed to the slave market to purchase a domestic servant for his wife, Susannah. The Wheatleys were a prominent middle class family in Boston. While at the slave market, John took pity on the tiny, sickly girl and purchased her. They named her Phillis, after the ship that brought her to Boston, and Wheatley, the surname of her owners.

Before long, however, Susannah realized that Phillis was very intelligent and a quick leaner. So she decided to provide her with an education. She still had some domestic duties, but most of her time was spent on her studies. Susannah and her daughter, Mary, tutored Phillis in reading, writing, language (Greek and Latin), literature, history, astronomy, geography, and religion.

Phillis wrote her first poem when she was 13 years old. Her poem “On Mssrs. Hussey and Coffin, described the men’s adventures at sea. They had nearly drown at sea during a storm, but miraculously survived. The poem was published on December, 21 1767 in the Newport, Rhode Island newspaper, Mercury. And it was just the beginning.

Want to Know More?

Phillis Wheatley, Letters of Phillis Wheatley, the Negro Slave-Poet of Boston, (1864).

Phillis Wheatley, The Collected Works of Phillis Wheatley (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988).

Brown, Drea. “The Multiple Truths in the Works of the Enslaved Poet Phillis Wheatley.” Smithsonian Magazine (June 24, 2020).

O’Neale, Sondra. “Phillis Wheatley, 1753-1784. Poetry Foundation” (https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/phillis-wheatley)

Vincent Carretta, Phillis Wheatley: Biography of a Genius in Bondage (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2011).