Brilliant Businesswoman

She dreamed of being a lawyer in an era where women were not weren’t even allowed to own their own property. It was a long and winding path to achieve that goal, including working at her husband’s law office, writing bills to provide women with legal rights, helping former First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln get released from insane asylum, and publishing a legal newspaper. Travel back in time to 1871 Chicago and meet Myra Bradwell…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

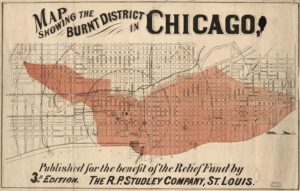

Myra Colby Bradwell stood in the street and and stared at the charred remains of her thriving business. It was October 11, 1871 and her family just lost nearly everything in the Great Chicago Fire. Their home was completely destroyed. And the offices of the Chicago Legal News burned to the ground. But that didn’t stop Myra.

Thankfully, their 12-year old daughter, Bessie, grabbed the newspaper subscription book before fleeing as the flames neared the building. Myra found a publishing company in Milwaukee, Wisconsin that could print the newspaper on a last minute basis. So she grabbed the subscription book and hopped on a train.

Portrait of Myra Bradwell

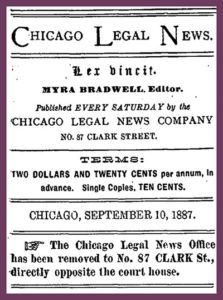

Myra wrote the October 14, 1871 edition from a hotel room in Milwaukee. And the Chicago Legal News was published on time. It was quite an accomplishment. In fact, it was the only newspaper in Chicago to not miss an edition after the fire. After three years of operating the Chicago Legal News, she still got a thrill from seeing her name on the front page in black and white — “Myra Bradwell, Editor.”

Myra had started the Chicago Legal News back in 1868. But it wasn’t easy. Quite a few people were surprised by her plans — it wasn’t considered “ladylike” to run a business. In addition, Myra had to obtain a special permit from the state of Illinois before she could start a newspaper. Because she was a woman.

Back then, Myra couldn’t sign contracts on her own behalf because she was a married woman. So she petitioned the state legislature for a special charter. She was granted “feme sole” status, which gave her the ability to own a business, sign contracts and keep her earnings (instead of turning them over to her husband).

Within a decade, the Chicago Legal News became the most widely circulated legal newspaper in America. It was an indispensable source of news for lawyers and revolutionized legal publishing. The Chicago Legal News included a wide variety of information — court opinions, new laws, forms, land titles, contract notices, and attorney profiles.

Area burned by Chicago Fire of 1871 (Library of Congress)

Myra also used the Chicago Legal News to advocate for social change. She published pieces on issues ranging from women’s suffrage, prison reform, establishing law schools (and admitting women), to railroad regulation. She even wrote a column named “Law Relating to Women.”

Myra knew the importance of publishing first — she wanted lawyers to turn to the Chicago Legal News for recent court opinions and new laws. So Myra arranged with Illinois state officials to receive copies of new laws and court opinions immediately after they were passed. Then, she went further. The Chicago Legal News became the official publisher of legal records for the state of Illinois. Myra also obtained approval from federal circuit courts to publish their opinions as well.

Through her efforts, Myra established the Chicago Legal News as the primary source of legal information in America. And made history as the first woman to be editor of a legal publication in America.

The Power of the Wand

Over her career, Myra was a savvy businesswomen, brilliant publisher and lawyer, and relentless champion for women’s legal rights. She was also instrumental in opening both higher education and legal careers to women (she helped over 25 women around the country become lawyers and participated in the effort to allow women lawyers to argue cases before federal courts). Since then, generations of women have benefitted from Myra’s efforts. Today, over 50% of students in ABA-approved law schools are women. Myra would be thrilled!

Her Yellow Brick Road

Myra was one of the first women to practice law in America. She was an apprentice in her husband’s law office, getting a legal education while also helping him with his career. Eventually, she decided to take the Illinois bar exam and passed with flying colors in 1869. She was denied admission to the Illinois state bar, however, because she was a woman. By then, she had her hands full with the newspaper and didn’t really need a law license. But it was the principle that counted — she was fighting for all woman that would come after her.

Myra filed a lawsuit to be admitted into the bar in 1870. But she lost. In Bradwell v. Illinois, the Illinois Supreme Court held that Myra was disqualified from receiving a bar license because she was married. Her status as a married woman made Myra “disabled” — she didn’t have a separate legal existence from her husband and couldn’t sign legal contracts.

Myra filed a lawsuit to be admitted into the bar in 1870. But she lost. In Bradwell v. Illinois, the Illinois Supreme Court held that Myra was disqualified from receiving a bar license because she was married. Her status as a married woman made Myra “disabled” — she didn’t have a separate legal existence from her husband and couldn’t sign legal contracts.

So Myra appealed the decision to the US Supreme Court. Her friends, Susan B Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, filed briefs in her support. But it wasn’t enough. After three years of sitting on the case, the Supreme Court finally upheld the Illinois decision in 1873. The concurring opinion stated that: “the natural and proper timidity and delicacy which belongs to the female sex evidently unfits it for many of the occupations of civil life.” Myra wasn’t surprised. And she was determined to prevail in the long run.

Throughout her career, Myra was dedicated to improving women’s role and legal status in society. She wanted equal citizenship for all women. And she worked with other activists to write new laws that afforded legal rights to women. For example, she co-wrote the Illinois Married Women’s Property Act of 1861, which gave married women the right to own and sell real estate. However, Myra didn’t think that the law went far enough. So she continued to push for more.

Chicago Legal News (Library of Congress)

Myra wrote a new bill, the Married Women’s Earnings Act, and lobbied for its passage in the Chicago Legal News. It became law in 1869 and finally gave women control over their own finances. Her intent was for women to be treated exactly the same as men. So she also pushed for changes to laws regarding divorce and custody, as well as equal employment and sex discrimination laws.

Then, Myra tackled another women’s rights issue — the ability of a husband (other other family member) to request that a woman be declared “insane” and institutionalized. In 1875, she led a publicity campaign to help her friend and former first lady, Mary Todd Lincoln. Mary’s son, Robert, became concerned about her erratic behavior and instigated proceedings to have her declared insane. It was a sham proceeding: she was brought to the courthouse an hour before her “trial” began, which lasted three hours with virtually no defense. It took the jury 10 minutes to return a verdict and Mary was involuntarily committed to Bellevue Place, a private insane asylum just outside of Chicago. Mary wanted her freedom back and smuggled a letter to Myra, asking for help. Myra visited Mary at Bellevue and became convinced she didn’t belong in an institution. So she and James advocated for Mary’s release. Myra published stories about Mary’s condition and her treatment at Bellevue Place. She also brought journalists to meet Mary at Bellevue. Finally, Robert Lincoln relented. Mary left the sanatorium in September 1875, about four months after her insanity trial.

Brains, Heart & Courage

When Myra was 12 years old, she and her family made the long journey from New York to Elgin, Illinois. Her parents became prominent abolitionists in town and active members of the Underground Railroad. Over time, like-minded people gathered at the Colby home to discuss pressing issues of the day. Myra listened carefully to each lively discussion and learned the importance of fighting for what you believe in.

There were few educational opportunities for girls in Chicago at the time. So Myra lived with her aunt in Kenosha, Wisconsin and went to a private girls school. Then, Myra moved back home to finish her studies at the Elgin Seminary for Females, which had just opened. After graduation, she became a teacher at the seminary.

Myra met James Bradwell, who was from an immigrant family who has a small farm about 20 miles away. He had worked his way through college by doing manual labor. He had no money and no social standing and her parents opposed the match. But Myra was in love. So they eloped when she was 21 years old, a very rebellious move back then. Eventually, however, her family learned to accept the relationship.

Myra met James Bradwell, who was from an immigrant family who has a small farm about 20 miles away. He had worked his way through college by doing manual labor. He had no money and no social standing and her parents opposed the match. But Myra was in love. So they eloped when she was 21 years old, a very rebellious move back then. Eventually, however, her family learned to accept the relationship.

The couple moved to Memphis, Tennessee. There, James studied law and passed the bar exam. In addition, he and Myra opened a private school together (with Myra as teacher). Then, they moved back to Chicago a few years later, in 1855.

John opened a law practice with Myra’s brother, Frank Colby. Before long, they became respected members of Chicago’s legal community and were quite busy. Then, James was elected County Judge of Cook County in 1861. They officially had more work than they could handle. So Myra helped out at the office. And loved it.

After the Civil War began, Myra participated in various women’s clubs and enjoyed being surrounded by other strong, ambitious women. She served as President of the Chicago Soldier’s Aid Society, which assisted soldiers and raised money for the Union Cause. Before long, she realized that she wanted a career of her own.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- Myra Colby was born on February 12, 1831 in Manchester, Vermont as the youngest of five children. She lived in New York and Vermont until her family moved to Illinois when she was 12 years old. She attended finishing school and female seminary, since few colleges accepted women back then.

- Myra married James Bradwell in 1852. They had four children: Myra, Thomas, Bessie, and James (two died at an early age). Their daughter, Bessie, was admitted into the bar in 1879 — she was one of only 26 women throughout America at the time (Elizabeth Bradwell Helmer).

- Over time, James and Myra acquired a number of legal books and eventually owned the largest private library in Illinois.

- Myra started the Chicago Legal News in 1868 and served as it’s editor and publisher for over 20 years. She was a leader in the printing industry and the first woman member of the Illinois Press Association. Her children, Bessie and Thomas, took over management of the Chicago Legal News after Myra’s retirement. They managed the newspaper until 1925.

- Eventually, the Illinois Supreme Court approved Myra’s application to the bar in 1890 (she was 59 years old). And the US Supreme Court gave her an honorary license to practice law in 1892. She was also made an honorary member of the Illinois State Bar Association.

- Myra helped to bring the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. Then, she was appointed to the Board of Lady Managers for the event. She used her position to increase women’s participation and representation at the Exposition.

- Myra died of cancer on February 14, 1894 at age 63 (after a three year battle).

Want to Know More?

Emerson, Jason. The Madness of Mary Lincoln. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 2007.

Friedman, Jane. America’s First Women Lawyer: the Biography of Myra Bradwell. New York: Prometheus Books, 1993.

Garza, Hedda. Barred from the Bar: A History of Women and the Legal Profession. New York: F. Watts, 1996.

Norgren, Jill. Rebels at the Bar: The Fascinating Forgotten Stories of America’s First Women Lawyers. New York: NYU Press, 2013.

Wheaton, Elizabeth. Myra Bradwell: First Woman Lawyer. Greensboro: Morgan Reynolds, 1997.

Ruffine, Louisa S. “Civil Rights and Suffrage: Myra Bradwell’s Struggle for the Equal Citizenship for Women.” Hastings Women’s Law Journal, Volume 4, June 1, 1993. (accessed at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=1028&context=hwlj)

“Myra Bradwell: First Woman Admitted to Illinois Bar.” March 16, 2018. Illinois History and Lincoln Collections. (accessed at https://publish.illinois.edu/ihlc-blog/2018/03/16/myra-bradwell/).

Bradwell v. State of Illinois (83 US 130 (1872)) (accessed at: https://caselaw.findlaw.com/us-supreme-court/83/130.html)