Brilliant Businesswoman

She has led at least 9 different lives in her almost 100 years – a childhood journey from Detroit to New Orleans to Oakland, a wife, mother, WWII shipyard clerk, record store owner, civil rights activist, songwriter & performer, and legislative aide. But it is her last act – as the oldest National Park Ranger in the USA – that will be her legacy. Attend the 2000 planning meeting for the proposed Rosie the Riveter National Historic Park and meet Betty Reid Soskin…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

Betty Reid Soskin had a decision to make. She was in a meeting of National Park Service representatives and other stakeholders who were discussing plans for a new National Historic Park in Richmond, California. The National Park Service wanted the new Park to honor the contributions of the home front in World War II. During the war, Richmond had been a center of manufacturing for the military, with its shipyards and tank factories working as quickly as possible to supply what was needed to win the war. The scale of the mobilization was massive – building 740 ships built in less than 5 years.

Park Ranger Betty

Betty was at the meeting as a representative for her boss, Calfornia Assemblywoman Dion Aroner. In her 70s, when most people retire, Betty had started a new job as a field representative for Dion, working in a one woman office in Richmond doing constituent service. She loved the work, and now, in the year 2000, at age 79, found herself sitting at the table witnessing the birth of a National Park. Dion had asked Betty to sit in on the planning meetings and keep her updated on what was being discussed.

NPS intended to name the park after Rosie the Riveter, the nickname given to the women who kept the factories going while the men went to war. Betty’s job was to observe, listen, and report back to her boss, but as she listened to the historians and planners discuss the experience of the “Rosies,” she observed that as a Black woman, she had experienced the homefront very differently. Betty had to decide whether to speak up – she was the only person of color in the room. She figured she had nothing to lose, and declared to the assembled group that “there were no Black Rosies.”

That statement got the committee’s attention. They wanted to hear more. Betty explained that because unions were segregated, factories were segregated. While white women were allowed to work on the assembly lines, Black women were typically given menial or clerical jobs. Betty told them that she had never seen a battleship being built even though she worked for a shipyard. She instead worked as a file clerk for the Black auxillary of a segregated Boilermaker’s Union and didn’t even realize the role she had played in the mobilization until much later.

That statement got the committee’s attention. They wanted to hear more. Betty explained that because unions were segregated, factories were segregated. While white women were allowed to work on the assembly lines, Black women were typically given menial or clerical jobs. Betty told them that she had never seen a battleship being built even though she worked for a shipyard. She instead worked as a file clerk for the Black auxillary of a segregated Boilermaker’s Union and didn’t even realize the role she had played in the mobilization until much later.

The meeting made Betty realize that many other people’s stories were also not being told. Betty wasn’t angry or offended by the omission. Instead, she believed that “There was no conspiracy to leave my history out. There was simply no one in that room with any reason to know it.” And she agreed to become an active member of the planning committee.

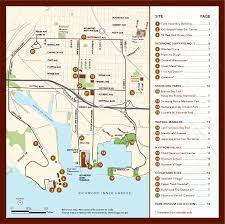

Map of the Rosie the Riveter/WWII Home Front National Historical Park (NPS)

Betty inspired the NPS to broaden its research and invite more diverse stakeholders to the table to share their experiences. She encouraged them to include of the impact the Port Chicago explosion had on the Black community, when 320 sailors and workers – 202 of them black men – died in an explosion of 2 cargo ships. And she emphasized that it wasn’t just the Black community who needed their stories told. Among others, there were Mexican immigrants and Native Americans who worked in the factories, as well as the Japanese Americans who were sent to internment camps. Betty helped the planners recognize that the home front was a patchwork quilt of experiences, and each square of the quilt was necessary to tell the complete story.

The Rosie the Riveter/ WWII Home Front National Historical Park opened in Richmond, California in October 2000. NPS preserved a ship, the four shipyards and the village where shipyard workers lived, and a tank factory. The Park also features one of the staging areas where Japanese citizens were required to report before being sent to an internment camp. NPS then added exhibits and oral histories to provide visitors context as to how industry, government, and citizens came together.

The Power of the Wand

Betty wanted to continue her involvement with the Park even after it opened. In 2006, at age 85, she became a National Park Ranger. For her first few years as a Ranger, Betty was a guide on a tour bus which drove visitors around to the various sites. She then moved to the Park’s theater, where she tells the story of the Rosies and her own experience. And while Betty doesn’t sugarcoat the discrimination she and others faced, she also shares her optimism that progress will continue to me made: History has been written by people who got it wrong, but the people who are always trying to get it right have prevailed. If that were not true, I would still be a slave like my great-grandmother.”

Today, Betty, at age 99, is the oldest National Park Service Ranger in the United States – and she became a Ranger at the age of 85! The National Park Service also has a Junior Ranger program for its younger visitors where participants take an oath to protect the Park, learn more about the Park and participate in activities with Rangers. Visit the list of National Parks with Junior Ranger programs here.

Her Yellow Brick Road

Betty and her husband Mel lived in Berkeley, California. Mel’s dream was to own a record store, and Betty helped him make Reid’s Records a reality. They found a storefront on Sacramento Street and opened in 1945. They built a loyal customer base by stocking music that many white owned stores were less likely to carry – like jazz, rhythm & blues, and gospel.

Betty, Mel, & their 4 kids (Reid Family)

By the 1950s, Reid’s Records was a success.. Betty and Mel were finally in a position to move to a house with enough room for their growing family. They couldn’t find what they wanted in Berkeley because of a practice called redlining, where the government and banks used mortgage restrictions to keep certain neighborhoods whites only.

They found a nice empty lot in nearby Walnut Creek, but still had to have a white friend sign the deed for them. Once word got out that a Black family was building a house on their street, trouble started. They received death threats and threats to destroy the house. Betty and Mel decided not to back down, gambling that it was only a small number of people who objected. They traded off guarding the house as it was being built. And when they moved in, they discovered their hunch that the threats would fade was correct. They got to know their neighbors and had two more kids.

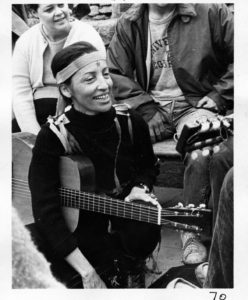

Betty performing in the 1960s (Reid Family)

Betty joined the local Unitarian Universalist Church and got involved in their racial and social justice work. Many of her fellow congregants were white, and she felt the same “racial limbo” she had experienced growing up. Betty advocated for Civil Rights and against the Vietnam War. Betty became a supporter of the Black Panther Party, which was founded in Oakland in 1966 to challenge police brutality and offer social programs like free meals for children. She was in a unique position to raise money for the Party from her liberal white neighbors – she hosted fundraisers and went door to door explaining what the Black Panthers were doing and then delivered the money to its organizers.

As Reid’s Records expanded into concert promoting and Mel spent a lot of time on the road, their marriage suffered. Betty began to suffer serious panic attacks, which often left her unable to drive across bridges or through tunnels, severely restricting her mobility in a town with many of both. Betty turned to music as therapy and set aside time with her guitar to compose melodies and lyrics that captured her feelings. She started performing her songs in public and Capitol Records eventually offered her a recording contract. She declined, believing it wouldn’t work with her responsibilities at home.

Betty and Mel divorced in 1972 and Betty married a Berkeley professor named Bill Soskin. Betty again found herself in “racial limbo” as a Black faculty wife married to a prominent white man. She leveraged her access to influential people to advocate for racial and economic justice. They had a happy marriage that ended in a pre-planned divorce when Bill entered a Buddhist monastery.

Betty and Mel divorced in 1972 and Betty married a Berkeley professor named Bill Soskin. Betty again found herself in “racial limbo” as a Black faculty wife married to a prominent white man. She leveraged her access to influential people to advocate for racial and economic justice. They had a happy marriage that ended in a pre-planned divorce when Bill entered a Buddhist monastery.

Meanwhile, Mel had made some bad financial decisions that brought Reid Records to the brink of bankruptcy. Betty took over and revitalized the business. She wanted the drug dealers out of the surrounding area and lobbied Berkeley’s City Hall to get it done. She was instrumental in the city investing $8 million to re-develop the community. She developed a reputation as strategic and persuasive and one of the council members, Don Jelinek, offered her a position as a legislative aide. Betty said yes, because she had learned the importance of having a seat at the table where decisions are being made. This position eventually led her to a job in the California legislature, working as an aide to Assemblywoman Dion Aroner.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Alhough Betty’s dad’s family had lived in New Orleans since 1631, but she was born in Detroit, Michigan. Her parents had to flee north before she was born after her dad “insulted” a white man by using his first name in conversation. When she was 3, the family returned to New Orleans. Her dad’s family was Creole – part of a group of people with African, French, Spanish, and Native American roots who had higher social and professional status than other Black residents in New Orleans. Betty’s mom was of Cajun/African descent and her maternal great-grandmother was born into slavery. Betty grew up with a sense that she lived in a “racial limbo.”

Betty in the middle of her sisters (Reid Family)

When Betty was 6, the Great Mississippi Flood destroyed many areas around New Orleans – particularly those where its Black residents lived. The family decided to rebuild their lives in California, where Betty’s grandpa already lived. They took the train across the country and settled with him in Oakland. Betty spent most of her time at the nearby estuary, where she caught butterflies and dragonflies in jelly jars and brought salamanders home as pets. Their neighborhood was racially diverse, and her parents made an effort to stay connected with the other Creole families who had moved west too.

Betty was small and relatively frail compared to her sisters, which increased her risk for tuberculosis. Her parents sent her to a preventorium in the California valley where she underwent treatments to keep her healthy. She lived there for a year, and when she returned, felt like a stranger in her own house. Betty turned to books for company and became a voracious reader.

World War II Era Betty (Reid Family)

Betty felt the “racial limbo” again when she entered high school. She and her sisters were some of the only Black students at the school. Her mom told her to take Spanish instead of French like her older sister. Her reasoning: Betty’s skin was the darkest in the family so she “looked more Spanish.” When Betty auditioned for the lead in the school play, she wasn’t cast because she would act opposite a white boy and his parents would object. She found a group of Black college kids who she spent most of her time with – among them baseball legend Jackie Robinson, who she dated for a bit!

Betty didn’t believe that college was an option for her – as a teen, she didn’t question the expectation that her choices were limited to working in agriculture, working as a domestic, or getting married. She found a job as domestic help for a white family. Her first weekend with them, she worked 12 hour days cleaning, cooking, and caring for their children. Although the going rate was 50 cents an hour, at the end of the weekend, the woman paid Betty 50 cents total. Betty walked out of the door, cried on the bus ride home, and decided she wasn’t going back. Instead, she ended up marrying young – at age 20 and then getting a job as a file clerk for a shipyard once World War II started and employees were in demand.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- Betty Charbonnet was born on September 22, 1921 in Detroit, Michigan.

- In 1972, Betty’s local Democratic caucus elected her to go to the Democratic National Convention as a delegate for Presidential candidate George McGovern.

- Betty was named a “Woman of the Year” by the California State Legislature in 1995. Ten years later, she was named one of the National Women’s History Project’s “10 Outstanding Women” who are “builders of communities and dreams.”

- President Barack Obama invited Betty to light the National Christmas Tree in 2015 and presented her with a commemorative coin with the presidential seal to honor the occasion.

- The National WWII Museum awarded Betty the Silver Service Medallion in 2016.

- Betty got her first computer when she was 82. She started doing research on her family and realized how hard it was to trace ancestry through women because their last names change with marriage. As a result, she decided to start a blog writing about her life stories to preserve them for her family. One of her cousins is a writer/journalist and persuaded her to let him edit the stories into a book, and that book Sign My Name to Freedom: A Memoir of a Pioneering Life was published in 2018.

- The women in Betty’s family live long lives. Her great-grandmother, who was enslaved from birth until Emancipation (1846-1865) lived to 102. Her mom and grandma lived into their 90s.

- Betty sang a song with the Oakland Symphony in December 2018. She described it as “the most wonderful thing I have ever done.”

Want to Know More?

Soskin, Betty Reid. Sign My Name to Freedom: A Memoir of a Pioneering Life (Hay House 2018).

Soskin, Betty Reid. “I’m 99 and the Oldest Park Ranger in America” (Newsweek Oct. 11, 2020).

Chideya, Farai. “The 97-Year-Old Park Ranger Who Doesn’t Have Time for Foolishness” (Glamour Magazine Nov. 22, 2018).

Staff. “Women’s History Month An Interview with 93-Year-Old National Park Service Ranger Betty Reid Soskin” (Department of Interior Mar. 17, 2015).

White, Daphne. “Betty Reid Soskin: The Extraordinary Life of the Nation’s Oldest Park Ranger” (Berkeleyside Feb. 7, 2018).