Culture Changer

She had no idea what she wanted to be when she grew up, and spent years drifting without a sense of purpose. On a trip to England, she visited the world’s first settlement house, which provided services to the poor residents of London. She returned to her home in Chicago determined to create something similar in one of its toughest, poorest neighborhoods. Her founding of Hull House helped lift thousands out of poverty. She had a soft spot for the children she served, which led to the creation of many programs and activities for them, including the first public playground in Chicago. Step back in time to 1894, walk into a bright sunny acre of open space, smile at the children swinging while they laugh with glee, and meet Jane Addams…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

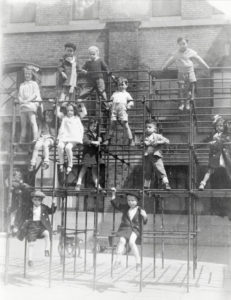

Jane Addams looked at all the kids playing around her and smiled. It was May 1, 1894 — opening day of the Hull House Playground. Jane was convinced that children needed a safe place to play and did whatever it took to make it happen. It was a novel idea at the time. In fact, the Hull House Playground was the first public playground in the city of Chicago.

It all started about one year earlier, when Jane and her friend, Florence Kelling, became concerned about the dilapidated tenement building next to Hull House. It was unsafe and unsanitary. So they went to the press about it. The publicity got the attention of William Kent, the owner of the building. He came out to inspect it and agreed it was in terrible condition.

Hull House Playground (University of Chicago Daley Library)

Jane had the perfect solution — donate the property to the Hull House. At first, Mr. Kent couldn’t believe the nerve of this woman. Just give away an acre of land? But then he learned more about what she was doing at Hull House and her hopes for the future. And the idea became more attractive to him. So he donated the property to Hull House. A few days later, the tenement building was torn down. Before long, the land was transformed into a safe place for children to hang out together and play.

The Hull House Playground was state of the art — nearly one acre of open space in the middle of Chicago. There were activities for children of all ages. Younger children had a sandbox, swings, paving blocks, and a “giant stride.” It was one of the first pieces of playground equipment (it was a tall pole with ropes suspended from a revolving disk. Children would grab a rope and swing themselves around the pole). Older children had open space to play baseball and handball. And it was a huge hit!

Back then, there were very few opportunities for children to play in America’s cities. Kids played in alleys that were full of garbage, rats, mud, and horse manure. Or they played in the streets, which were busy and could be dangerous. Older boys roamed the city in gangs and got themselves into trouble.

The Hull House Playground was so popular that it got a lot of press. And the idea took off. In 1900, there were only a few playgrounds in Chicago for 500,000 children. Within 5 years, however, Chicago had an ambitious plan for neighborhood parks and playgrounds. It became the first city to create a network of neighborhood playgrounds and served as a model for other American cities. In fact, newspapers called playgrounds the “best investment Chicago has ever made.” And it all started with Jane’s vision for the Hull House Playground.

The Power of the Wand

Millions of children have benefitted from Jane’s work. Literally. She created opportunities for children that didn’t previously exist — kindergartens, day care, art and music schools, parks and playgrounds. Eventually, many of her programs were replicated throughout America.

For example, Kaboom.org is furthering Jane’s legacy for today’s generation. It’s a nonprofit organization that provides kids around the nation with inspiring play spaces. The goal is to transform everyday spaces into play areas, especially in urban communities.

Her Yellow Brick Road

Jane was 27 years old when she finally figured out what she wanted to do with her life. She wanted to create a settlement house to serve the poorest residents in the slums of Chicago.

It took Jane five years to find the perfect place. She found an abandoned mansion in the 19th Ward — Chicago’s toughest, poorest neighborhood that was home to a diverse group of immigrants. The house had been built many years earlier by Charles Hull and his cousin, Helen Culver, had inherited it. Jane signed a lease without hesitation. Then, she invited some of her friends to move into Hull House with her. Many of the women involved in Hull House went on to become progressive leaders themselves.

Hull House (Swarthmore College Peace Collection)

The goal of Hull House was to “provide a center for higher civic and social life, maintain educational and philanthropic enterprises, and improve the conditions in the industrial districts of Chicago.” When Helen learned what Jane and her friends were doing, she stopped charging them rent. Eventually, she gave them the house and land. Money always tight at Hull House. Jane never took a salary, but used her inheritance and donated all proceeds from her speaking engagements, books and articles. She went broke to keep her dream alive.

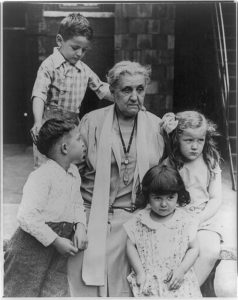

Hull House was a place where immigrants from all communities could learn the tools needed to be successful in America. Jane’s goal was to improve their lives through education, job placement, and social services. And it evolved over the years to meet the needs of community. By its second year, Hull House served 2,000 people every week (including children from over 20 nationalities).

Jane Addams surrounded by children at Hull House (Library of Congress)

Eventually, Hull House grew to include 13 different buildings and offered a wide variety of services — kindergarten and daycare, job training and placement services, English and citizenship classes, art gallery, art and music classes, cooking classes, public kitchen, gymnasium, swimming pool, book bindery and library, and meeting space for trade unions. The list goes on and on.

Hull House became a center for social reform in Chicago. And Jane worked to improve city laws on housing, sanitation, factory conditions, public welfare, juvenile justice, women’s rights and child labor. Many people in Chicago didn’t like what Jane was doing, however — she was blasted in the newspapers; she was maligned by businessmen; and she was condemned by politicians. But Jane persisted.

Jane lived and worked at Hull House for over 40 years. Her view was that, in a democracy, an individual’s morality is not enough — every single person also has a duty to society. She dedicated her life towards fulfilling that duty. She lived and worked at Hull House for over 40 years and met the needs of the surrounding communities. Then, she advocated for change at the city, state, and federal level. And she improved the lives of millions of people as a result.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Jane grew up in a life of privilege. Her father was a wealthy miller and merchant in a small town. Jane was a voracious reader and worked her way through her dad’s entire library. She was rebellious and didn’t accept conventional thought. She was precocious, a deep thinker, and felt things intensely.

Jane Addams (Library of Congress)

Luckily, Jane’s dad encouraged her to get an education. And he gave her the space to become an intellectual when women were expected to be religious. But everyone has limits — Jane wanted to attend Smith College and get a college degree, which was too progressive for her father. He said no. Instead, he insisted that she attend Rockford Female Seminary, a traditional path for girls at the time.

Jane graduated from Rockford Female Seminary at the top of her class (she was valedictorian). They did not award college degrees, however. But she refused to give up. Jane convinced the Seminary to award college degrees one year later and she finally received the diploma she wanted so badly.

Then, Jane floundered. She lacked purpose and was lost after graduating from seminary. Jane wanted to make the world better but didn’t know how. She enrolled in medical school, but then became gravely ill and couldn’t attend.

As part of her recovery, Jane traveled to Europe. When she visited London, Jane saw poverty that she didn’t know existed. Her eyes were opened. And it changed her forever — she was shocked at people’s indifference to human need and horrified that poverty and squalor were just accepted as part of society.

As part of her recovery, Jane traveled to Europe. When she visited London, Jane saw poverty that she didn’t know existed. Her eyes were opened. And it changed her forever — she was shocked at people’s indifference to human need and horrified that poverty and squalor were just accepted as part of society.

When Jane visited Europe for the second time in 1884, she visited Toynbee Hall in London’s East End (AKA Whitechapel, the stomping ground of Jack the Ripper). It was the world’s first settlement house — University men lived in the slums and helped their neighbors. The men used their education to provide classes and other activities for residents in the community. It was the inspiration that Jane needed. She was determined to create a settlement house in Chicago.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- Laura Jane Addams was born on September 6, 1860 in Cedarville, Iowa. She was the 8th of 9 children (only 5 lived to adulthood). Her mother died when Jane was 2 years old and her older sister cared for her. Her dad remarried when she was 7 years old.

- Jane’s dad was a prosperous miller and merchant. He served in the Civil War, was elected to the state legislature and considered Abraham Lincoln to be a friend.

- Jane had a spinal curve (scoliosis) which caused her pain for many years.

- Jane attended Rockford Female Seminary and graduated top of her class in 1884.

- Jane received a few marriage proposals but never married.

- Jane was dedicated to improving the neighborhood surrounding Hull House and to serve as a resource for all its residents. Most of the earliest activities at the Hull House were for the benefit of children.

- Jane was tireless in her advocacy of social reform and was involved in many organizations over the years. Here are just a few:

- Founding member of the National Child Labor Committee

- Founding member of the Chicago Playground Association

- Vice President of the Playground Association of America

- Vice President of Campfire Girls

- President of the National Conference of Charities and Corrections (president)

- Vice President of the National American Woman Suffrage Association

- Founding member of the NAACP

- Founding member of the ACLU

- President of the Women’s Peace Party

- President of the International Congress of Women

- President of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom

- Jane was the first woman to receive an Honorary degree from Yale University.

- Jane helped to establish the school of social work at University of Chicago, as well as the Chicago School of Civics and Philanthropy.

- In the second half of her life, Jane became a pacifist and traveled internationally to try to prevent World War I. She eventually was alone in her opposition to war. But she never wavered. Then, she helped Herbert Hoover provide food and supplies to the women and children of enemy nations.

- Jane was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1931. She was the first American women to be granted the honor. She donated the prize money to the Hull House and the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom.

- Jane was a prolific speaker and author — she wrote 11 books and many articles over the years.

- Jane died of abdominal cancer in Chicago on May 21, 1935.

- December 10 is Jane Addams Day in Illinois.

- Jane’s personal papers and documents relating to Hull House are part of the Jane Addams Collection, which is held by the Swarthmore College Peace Collection.

Want to Know More?

Addams, Jane. Twenty Years at Hull House: With Autobiographical Notes. The MacMillan Company, 1912.

Addams, Jane. The Spirit of Youth and the City Streets. The MacMillan Company, 1909.

Linn, James Weber. Jane Addams: A Biography. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2000.

McArthur, Benjamin. “The Chicago Playground Movement: A Neglected Feature of Social Justice.” Social Service Review. Vol. 49, No. 3 (September 1975), pp. 376-395.

Reynolds, Jerry. (2017). Jane Addams’ Forgotten Legacy: Recreation and Sport. Journal of Issues in Intercollegiate Athletics. 2017 Special Issue (July 2017), pp. 11-18.

The Hull House Museum (https://www.hullhousemuseum.org/)

Unfinished Business: The Right to Play (http://hullhouse.uic.edu/hull/rec/zine.html)