Passionate Patriot

She was a Montana girl who left her family ranch in search of her true calling. She found it in the suffrage movement and became the first woman elected to the United States Congress. She became a well-known anti-war advocate who also fought for women’s rights and worker safety . But after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, she had to choose between her conscience and her career. Walk onto the floor of Congress in 1941 and meet Jeannette Rankin…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

Jeannette Rankin knew what she had to do, but spent a minute gathering her courage and resolve to do it. It was December 8, 1941 and Jeannette was on the floor of the United States House of Representatives. It was her third term as a Congresswoman from Montana, but there had been 22 years between this term and her first two. Back then, she had been part of the Congressional debate over whether to enter World War I. Today, the House was debating whether to enter World War II.

Jeannette had established her anti-war credentials during World War I and afterwards. In 1917, Jeannette had been one of only 50 representatives to vote against the U.S. declaration of war against Germany. After World War I ended, Germany became increasingly aggressive once Adolf Hitler and his Nazi party consolidated power and started moving through Europe. In 1929, the National Council for the Prevention of War hired Jeannette to be their chief Washington lobbyist and speaker, and she served in that role for 10 years. Jeannette developed a national reputation as a strong voice for progressive causes. She decided to run again for Congress in 1940, won, and returned to Washington, D.C. in 1941 to serve.

Jeannette had established her anti-war credentials during World War I and afterwards. In 1917, Jeannette had been one of only 50 representatives to vote against the U.S. declaration of war against Germany. After World War I ended, Germany became increasingly aggressive once Adolf Hitler and his Nazi party consolidated power and started moving through Europe. In 1929, the National Council for the Prevention of War hired Jeannette to be their chief Washington lobbyist and speaker, and she served in that role for 10 years. Jeannette developed a national reputation as a strong voice for progressive causes. She decided to run again for Congress in 1940, won, and returned to Washington, D.C. in 1941 to serve.

Jeannette found herself a lone voice for peace and social justice. There were other House members who were anti-war, known as the “America First Committee” but they opposed New Deal social welfare programs. During most of 1941, Jeannette fought for legislation that would limit the chance that the United States would get pulled into the war.  She asked for an amendment requiring specific approval from Congress to send US troops abroad in the Lend-Lease Bill, sponsored a resolution condemning any effort to send US troops outside of the Western Hemisphere, opposed the draft, and opposed President Roosevelt’s request to arm US merchant ships. While unsuccessful, these efforts were supported by many of her colleagues who were wary of another war.

She asked for an amendment requiring specific approval from Congress to send US troops abroad in the Lend-Lease Bill, sponsored a resolution condemning any effort to send US troops outside of the Western Hemisphere, opposed the draft, and opposed President Roosevelt’s request to arm US merchant ships. While unsuccessful, these efforts were supported by many of her colleagues who were wary of another war.

The mood in Congress shifted dramatically after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. President Roosevelt called a special session of Congress for a debate and vote on a declaration of war against Japan. The Mutual Radio Network, which had broadcast the president’s address, continued broadcasting in the House Chamber. As a result, most of the House debate was broadcast live.

Jeannette strongly believed that war would cost so many American lives that it should be avoided if at all possible. She rose and asked to be allowed to speak. The Speaker of the House refused and told her she was out of order. Her colleagues were either shouting for her to sit down or asking her either to vote for the war or abstain from voting altogether. Jeannette, true to herself, answered “Nay” when her name was called for her vote. She added “As a woman I can’t go to war, and I refuse to send anyone else.” The declaration of war passed 388-1.

Jeannette strongly believed that war would cost so many American lives that it should be avoided if at all possible. She rose and asked to be allowed to speak. The Speaker of the House refused and told her she was out of order. Her colleagues were either shouting for her to sit down or asking her either to vote for the war or abstain from voting altogether. Jeannette, true to herself, answered “Nay” when her name was called for her vote. She added “As a woman I can’t go to war, and I refuse to send anyone else.” The declaration of war passed 388-1.

Her fellow House members and the spectators in the galley booed and hissed, and she had to hide in a phone booth until the police could arrive to safely take her out of the chamber and to her office. Jeannette paid a heavy price for her convictions. Her brother told her “Montana is 100% against you.” She was ignored for the rest of her term.

Jeannette had no regrets, saying “what one decides to do in crisis depends on one’s philosophy of life, and that philosophy cannot be changed by an incident. If one hasn’t any philosophy in crises, others make the decision.”

The Power of the Wand

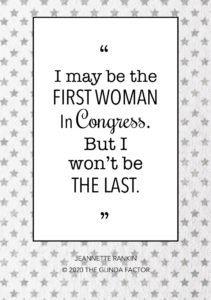

As the first woman ever elected to Congress, Jeannette gave women their first seat at the table. She decided not to worry about society’s disapproval of women who seek to participate in government, observing that “the individual woman is required . . . a thousand times a day to choose either to accept her appointed role and thereby rescue her good disposition out of the wreckage of her self-respect, or else follow an independent line of behavior and rescue her self-respect out of the wreckage of her good disposition.”

Kimberly Mitchem-Rasmussen is passionate about inspiring girls to aspire to a political life. She is the founder and President of the Girls in Politics Initiative, which offers a variety of civic education camps and classes for girls ages 6-17. At Camp Congress for Girls, attendees experience what it is like to run for office, vote in an election, and then serve in either the House of Representatives, Senate, or as President.

Her Yellow Brick Road

As a young adult, Jeannette bounced between jobs, looking for work that fulfilled her. She found it when she joined the suffragette movement. She became a professional lobbyist for the National American Woman Suffrage Association (“NAWSA”). NAWSA lobbied state legislatures on two issues: 1) allowing women to vote in their states and 2) approving an amendment to the U.S. Constitution ensuring the right nationwide.

Jeannette speaking from the NAWSA Balcony in 1917.

Jeannette traveled around the country making speeches and rallying supporters for suffrage. She fought particularly hard in her home state, and Montana finally granted women the right to vote in 1914. Now that women could vote, Jeannette decided to run for office herself. She was well-connection from her lobbying work and had a supportive brother willing to finance her campaign.

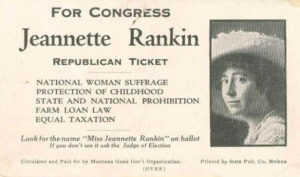

Many suffragettes tried to talk Jeannette out of running, fearing she would lose and damage suffrage movements in other states. But the Montana Republican Party thought a woman candidate would attract interest and attention to the race, so they nominated Jeannette for one of the two Montana seats. Montana elected two Representatives statewide, so all candidates were on the ballot and the top two won.

Jeannette’s campaign focused on nationwide women’s suffrage, caring for the less fortunate in society, and opposition to the United States intervening in World War I. The election was a first for Montana in many ways – the first one where women could vote for Congress and the first one where a woman ran for that office. Jeannette finished second, with over 6000 votes more than the next candidate.

Jeannette’s campaign focused on nationwide women’s suffrage, caring for the less fortunate in society, and opposition to the United States intervening in World War I. The election was a first for Montana in many ways – the first one where women could vote for Congress and the first one where a woman ran for that office. Jeannette finished second, with over 6000 votes more than the next candidate.

Jeannette spent much of her first term fighting for workers’ rights. Montana had a huge copper mining industry, and miners went on strike to demand safe working conditions and access to adequate health care. They reached out to Jeannette for help, but the mining companies refused to talk with her. She then took a big political risk and asked the federal government to nationalize the Anaconda copper mine and resolve the strike. When her request was denied, Jeannette feared the mining companies would retaliate because “They own the State. “They own the Government. They own the press.”

Jeannette ran for re-election in 1916. Congress had been avoiding a war vote, but in April 1917, Germany declared its intent to attack all Atlantic shipping. President Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany to “make the world safe for democracy.” Jeannette and her fellow congressmen were sworn in during a special session called to debate the war. Jeannette did not speak up during the debate, which she later regretted. After much soul searching, she voted no, stating as she cast her vote that “I want to stand by my country, but I cannot vote for war.” The declaration passed by a 373-50 margin.

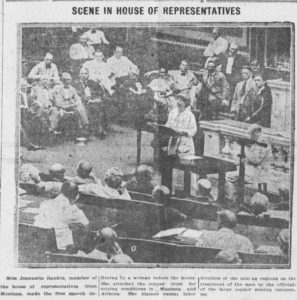

Jeannette’s first speech on the floor of Congress.

Eight months later, the House found itself debating another war declaration, this time against Austria-Hungary. Jeannette reluctantly voted yes, with the statement that “I still believe that war is a stupid and futile way of attempting to settle international disputes. I believe that war can be avoided and will be avoided when the people, the men and women in America, as well as in Germany, have the controlling voice in their government.” Although Jeannette was anti-war, she was pro-solider, and fought for generous allocations of resources for them.

Just before the war vote, Jeannette helped create a House Committee on Woman Suffrage, which in January 1918 presented a constitutional amendment granting women the right to vote. Jeannette opened the debate and asked her colleagues “how shall we explain to them the meaning of democracy if the same Congress that voted for war to make the world safe for democracy refuses to give this small measure of democracy to the women of our country?” The House voted yes, but the Senate voted no.

For the 1918 election, Montana decided to split into Congressional districts. Jeannette knew she would lose because the district she lived in was overwhelmingly Democratic. She decided to run for Senate to influence the suffrage debate there, but it was too late for her to get the Republican nomination. She ran as an Independent and finished third.

While Jeannette was no longer in Congress, she kept fighting for her beliefs. She agreed to be the “field secretary” for the National Consumers League. She traveled the country rallying people to support laws to improve health care for mothers and their children, ban child labor, and protect women workers. She worked for the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom and Women’s Peace Union. She briefly lived on a farm in Georgia and founded the Georgia Peach Society.

By 1940, the United States again was faced with the choice of whether to intervene in a European war. Jeannette felt the call to participate on the side of peace. She returned to Montana to run for the House of Representatives. She traveled throughout her district to talk with high school students about war and peace, as their generation would bear the brunt of any decision to go to war. She won the election and her term began in January 1941.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Jeannette grew up on a ranch in Montana. Her dad managed the ranch and her mom was a schoolteacher. She was the oldest of seven, and had many responsibilities. She cared for her siblings but also helped her dad with the ranch chores. She grew up working side by side with men as she baled hay and repaired farm equipment and learned to view herself as equally capable.

She graduated from Montana State University in 1902, but still wasn’t sure what she wanted to do with her life. She tried teaching school like her mom, but didn’t enjoy it. She did an apprenticeship as a seamstress and took a class on furniture design, but neither career resonated.

Jeannette flying the flag of suffrage during a demonstration in 1913.

Jeannette ventured to San Francisco and found work helping immigrants connect with social services. She was inspired enough to attend the New York School of Philanthropy. She then returned west to be a social worker in Spokane, Washington. She was horrified by the living conditions of the people she helped, and decided she wanted to have the power to change it. This led her to politics. She got involved with a women’s suffrage group, studied policy-making at the University of Washington in Seattle, and returned to New York.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- Jeannette was born near Missoula, Montana on June 11, 1880.

- She was the only Member of Congress to vote against U.S. participation in both World Wars.

- Jeannette chose not to run for re-election in 1942. She returned to her work on social justice and peace issues, while supporting herself as a seamstress and a teacher. She spent time in India during its campaign to win independence from Great Britain and was inspired by Mahatma Gandhi’s non-violent protest methods.

- When the Vietnam War began, she was a strong anti-war voice, founding the “Jeannette Rankin Brigade.” On January 15, 1968, at age 87, she led 5000 people in a protest march on Washington to present a petition for peace to the Speaker of the House.

- Jeannette was considering another run for House as an anti-war candidate when she died on May 18, 1973 at age 92.

- The Jeannette Rankin Foundation awards scholarships to women 35 years old or older “who through undergraduate or vocational education are seeking to better themselves, their families, and their communities.”

- Every state is allowed two statues to be placed in Washington D.C. to memorialize what is valued most by each state. Montana chose Jeannette Rankin for one of its statues, because she “embodied the spirit of Montana in her perseverance in standing, even alone, for her convictions.”

Want to Know More?

The Lone War Dissenter: Walter Cronkite Remembers Pearl Harbor, Jeannette Rankin (NPR’s All Things Considered Dec. 7, 2001).

Fort Missoula Museum Staff. Jeannette Rankin

Gov.info Editors. 100th Anniversary of the First Woman to Serve in the United States Congress

History.com Editors. Jeannette Rankin.

U.S. House of Representatives. Rankin, Jeannette 1880-1973