Passionate Patriot

She was a schoolteacher who used her talents as an educator, writer, and public speaker to become known worldwide as a suffragette and civil rights activist. She persuaded women to leverage influence in their communities into power at the ballot box, all while fighting the discrimination she faced as a Black woman. Take your place at her side at the 1913 Women’s Suffrage Parade and meet Mary Church Terrell…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

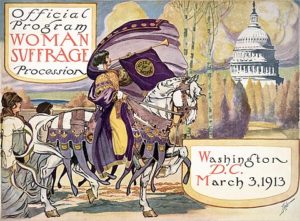

Official Women’s Suffrage Parade Program cover (Library of Congress)

Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.C. was filled with people on March 3, 1913, the day before President Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration. It was a different crowd than the one who would line the streets the next day for the inaugural parade. Over five thousand women from around the country were about to start marching in the Washington Women’s Suffrage Parade. It had been 65 years since the first women’s rights convention at Seneca Falls, and the women hoped to persuade the new president to act.

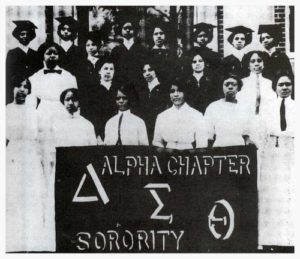

Mary Church Terrell was standing with 22 members of Delta Sigma Theta, a Black sorority she had helped organize just six weeks earlier at Howard University. Mary was a well-known activist who had been speaking and writing about racial and gender discrimination for over 20 years, often describing herself as a member of “the only group in this country that has two such huge obstacles to surmount…both sex and race.” This parade was a perfect example of this double disadvantage: in order to march in a parade intended to persuade a government of men of her right to vote, Mary first had to persuade an organization of women that she be allowed to participate.

Mary Church Terrell was standing with 22 members of Delta Sigma Theta, a Black sorority she had helped organize just six weeks earlier at Howard University. Mary was a well-known activist who had been speaking and writing about racial and gender discrimination for over 20 years, often describing herself as a member of “the only group in this country that has two such huge obstacles to surmount…both sex and race.” This parade was a perfect example of this double disadvantage: in order to march in a parade intended to persuade a government of men of her right to vote, Mary first had to persuade an organization of women that she be allowed to participate.

The parade organizer was the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). NAWSA’s plan for the parade was for women to march in groups according to their state or profession. NAWSA didn’t explicitly say the parade was for white women only, but it soon became obvious that it was. When Black women inquired at NAWSA headquarters about participating, they were told they had to register, but registry clerks were never available. Many gave up. Delta Sigma Theta students persisted and finally located a clerk, but their registration was rejected.

Diagram by Winsor McCay (Library of Congress)

The Delta Sigma Thetas asked Mary for help. With Mary involved, NAWSA made some initial concessions to avoid negative publicity. Its first offer was to allow Black women to participate if they promised to walk in the back of the parade, but Mary would not accept a segregated parade. She pushed and persuaded, and NAWSA agreed that the Delta Sigma Thetas would march with other University women near the New York delegation.

The parade began, and the thousands of women began making their way toward the White House. Mary was so proud of how wonderful the Delta Sigma Thetas looked in their caps and gowns amid the other University marchers as they made their way past the 200,000 spectators along the route. But the mood quickly turned as men in the crowd began harassing the marchers with verbal abuse, spitting on them, and pushing and grabbing. The police officers present did nothing, commenting that if the women didn’t want to be harassed, they should have stayed home.

Women’s Suffrage Parade (National Archives)

Mary and the other marchers moved forward as best as they could, using banner poles and hat pins to keep the men away. At some points, they were so surrounded by the angry mob that they couldn’t move. This continued for an hour, until U.S. Army soldiers arrived and cleared the street so the women could finish the route at Continental Hall, as planned. The men’s behavior backfired, as most newspaper coverage of the parade sympathized with the women and described their bravery.

(Library of Congress)

Out of the thousands who marched, only 40-50 of them were Black women, and Delta Sigma Theta was the only Black women’s organization present. The NCAAP magazine “The Crisis” praised the women in its April 1913 issue, observing that “in spite of the apparent reluctance of the local suffrage committee to encourage the colored women to participate, and in spite of the conflicting rumors that were circulated and which disheartened many of the colored women from taking part, they are to be congratulated that so many of them had the courage of their convictions and that they made such an admirable showing in the first great national parade.”

The Power of the Wand

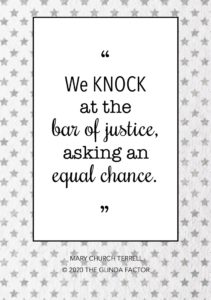

After the March, Mary kept working towards suffrage. Her message was simple: “how can any one who is able to use reason, and who believes in dealing out justice to all God’s creatures, think it is right to withhold from one-half the human race rights and privileges freely accorded to the other half, which is neither more deserving nor more capable of exercising them?” In 1919, Mary returned to Pennsylvania Avenue with her daughter Phillis. They were part of the Silent Sentinels, a group of women who picketed the White House every day for months, holding signs demanding the vote. The dream of suffrage was finally realized when the 19th Amendment was ratified on August 18, 1920.

After the March, Mary kept working towards suffrage. Her message was simple: “how can any one who is able to use reason, and who believes in dealing out justice to all God’s creatures, think it is right to withhold from one-half the human race rights and privileges freely accorded to the other half, which is neither more deserving nor more capable of exercising them?” In 1919, Mary returned to Pennsylvania Avenue with her daughter Phillis. They were part of the Silent Sentinels, a group of women who picketed the White House every day for months, holding signs demanding the vote. The dream of suffrage was finally realized when the 19th Amendment was ratified on August 18, 1920.

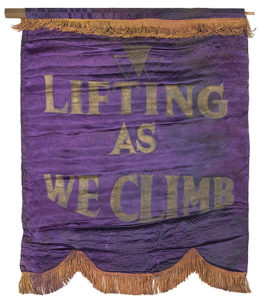

Delta Sigma Theta marked its centennial in 2013, and as part of their celebration, they hosted a re-enactment of the Women’s Suffrage Parade. Current members led the march, holding a banner that declared they were “Tracing the Footsteps of Our Founders.” They stopped at the steps of the U.S. Capitol, where Washington, D.C. Chief of Police Cathy Lanier, the first woman to hold that position, greeted them with these words: “for those of you with your sights set on the White House, I look forward to escorting you down Pennsylvania Avenue.”

Her Yellow Brick Road

Married women weren’t allowed to teach, so Mary left her position at a Washington D.C. segregated school after her 1891 wedding. Her time at the school had convinced her that the primary difference in the futures of Black and white children wasn’t aptitude, but opportunity.

Mary with kindergarteners in a Colored Women’s League sponsored class (NACW)

Mary observed that white children generally had access to better schools and community resources, which led to greater access to colleges and the job market. Those white children were more likely to become educators and business owners, continuing the cycle continued. The same barriers shaped the difference between the futures of boys and girls. Boys had more and better educational opportunities as children, which led to more power and independence as adults. A Black girl was doubly disadvantaged.

While Mary was contemplating these issues, she got word that her good friend, Thomas Moss, had been lynched by a white mob. His “crime” was being a Black man operating a successful business. His murder ignited an activist spark in Mary. She resolved to use her talents as an educator, writer, and speaker to pursue racial justice, oppose discrimination, and organize others to do the same. She founded the Colored Women’s League of Washington in 1892.

Mary spent the next 4 years submitting articles and opinion pieces to local and national newspapers and visiting church groups and community organizations to speak about the horrors of lynching, the damage done by racial stereotypes, and the challenges Black women faced in society. Mary connected with her audiences through her personal experiences and struggles. She always acknowledged her own relative affluence and good fortune but noted that neither protected her from discrimination based on her race and gender.

Mary spent the next 4 years submitting articles and opinion pieces to local and national newspapers and visiting church groups and community organizations to speak about the horrors of lynching, the damage done by racial stereotypes, and the challenges Black women faced in society. Mary connected with her audiences through her personal experiences and struggles. She always acknowledged her own relative affluence and good fortune but noted that neither protected her from discrimination based on her race and gender.

In 1896, the Colored Women’s League merged with the National Federation of Afro-American Women to form the National Association of Colored Women (“NACW”). The NACW elected Mary president and adopted her philosophy of “Lifting as we climb,” as its motto. Under Mary’s leadership, the NACW helped its members establish a variety of necessary community resources, including medical clinics, childcare, mother’s clubs, kindergartens, schools for girls, and nursing homes. The NACW became the leading Black women’s organization in the United States.

Mary’s term as NACW President ended in 1901, but she continued advocating on its behalf. Her lectures started emphasizing women’s suffrage because healthcare, education, and caregiving support wouldn’t become priorities until politicians needed women’s votes. Mary reminded her audience that they already had significant influence in their communities, and now needed to pair it with power at the ballot box.

Mary also urged women to work across racial lines to secure the vote. This was delicate work. Many suffrage organizations had been segregated since the 1860s, when the National Women’s Suffrage Association (“NWSA”) made a deliberate choice to oppose the 15th Amendment.

Suffragettes (NACW)

The NWSA feared Black men getting the vote would delay the vote for women. Although the opposition failed and the 15th Amendment was ratified in 1870, the continued struggle for women’s suffrage more than 30 years later hadn’t healed the breach. Mary decided to approach the NWSA’s leader, Susan B. Anthony, about working together. Susan started inviting Mary to speak at NWSA meetings about Black women and suffrage.

Mary filled the next few years building popular support for suffrage. She delivered one of her more famous speeches on June 13, 1904, when she spoke at the International Congress of Women in Berlin about what it was like to be a Black woman in America. She delivered her speech in German and French and received favorable press coverage for the cause.

Founding members of Delta Sigma Theta at Howard University (Delta Sigma Theta)

Mary was a founder and charter member of the National Association of Colored People in 1909 and the College Alumnae Club, which became the National Association of University Women, in 1910. Mary loved working with the University women, like the Howard University students who she helped start Delta Sigma Theta.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Mary was born in Memphis, Tennessee in 1863, the same year that President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. Her parents were freed slaves who moved to Memphis in search of work. They both started their own businesses. Her dad eventually became one of the South’s first Black millionaires and her mom owned and operated a successful hair salon.

Mary grew up in an affluent integrated neighborhood and her parents kept her and her brother relatively sheltered from racial injustice, even when her dad was injured during the Memphis Race Riots of 1866. But Mary’s grandmother made a point of educating her grandchildren about their family history, telling them her stories about being enslaved.

Mary (Oberlin College Archives)

Mary’s parents wanted to use their freedom and resources to provide their children with the education they were denied as enslaved children. They didn’t believe the segregated schools of Memphis could provide it and sent Mary to the Antioch College Model School, an integrated school in Yellow Springs, Ohio, when she was six. She stayed in Ohio for all of her schooling, moving to the Oberlin College Academy for high school. After graduating in 1880, she enrolled in Oberlin College and elected to take the “gentleman’s course” rather than the easier, shorter, women’s program. Mary’s parents divorced during her school years, so Mary started splitting her vacation time between her dad’s home in Memphis and her mom’s in New York City.

After college graduation in 1884, Mary initially moved back to Memphis because her dad didn’t want her to work. When he remarried, Mary moved back to Ohio to teach at Wilburforce College and take graduate classes at Oberlin. After two years, she moved to Washington, D.C. and continued work on her master’s degree thesis. Her dad was traveling to Europe and convinced her to join him. She jumped at the change to practice her French and German and spent two years abroad. In 1890, Mary returned to Washington, D.C. to teach at the M Street Colored High School, where she met her future husband.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- Mary was born September 23, 1863. Her family called her Mollie.

- During WWI, Mary sought to help the war effort by offering her French and German skills to the federal government, but most recruiters wouldn’t consider hiring a Black woman. She eventually found a position as an entry-level clerk, but quit due to the racial prejudice she faced on the job.

- Mary’s husband, Robert Heberton Terrell, was a federal judge for 14 years. He died in 1925. They had two daughters.

- During the 1920s and 1930s Mary worked on various senatorial and presidential campaigns, among them Rep. Ruth Hanna McCormick, who was the first female major party candidate for the U.S. Senate.

- Mary wrote a regular column for the Chicago Defender newspaper called “Up to Date” from 1927-1929.

- Mary published her autobiography, A Colored Woman in a White World, in 1940. In it, she vowed to continue her activism into her old age.

- Mary sued the American Association of University Women for discrimination. She won the lawsuit, and in 1948, became the first Black member.

- Mary was a member of the Coordinating Committee for the Enforcement of D.C. Anti-Discrimination Laws. In 1950, when she was 86, she was one of the diners who was kicked out of the John R. Thompson Restaurant in Washington, DC for refusing to serve them because they weren’t white. Terrell had helped organize sit-ins, pickets, boycotts, and surveys around the city. By 1953, the subsequent lawsuit reached the Supreme Court, which ruled that segregated eating facilities in Washington, D.C. were unconstitutional.

- Mary died July 24, 1954 at age 90, living long enough to see the Brown v. Board of Education ruling that declared “separate but equal” segregation unconstitutional and paved the way for integrated schools.

- Mary’s home at 326 T Street, N.W. in Washington, D.C. is a National Historic Landmark.

Want to Know More?

Church, Mary Terrell, “In Union, There Is Strength” (1897 Speech contributed by Blackpast Jan. 29, 2007).

Church, Mary Terrell. A Colored Woman in a White World. (Ransdell, Inc. Publishers, 1940).

Bernard, Michelle. “Despite the Tremendous Risk, African American Women Marched for Suffrage Too” (Washington Post Mar. 3, 2013).

Lewis, Jane Johnson. “Mary Church Terrell Biography and Facts” (ThoughtCo Dec. 15, 2018).

Library of Congress. “Mary Church Terrell: Advocate for African Americans and Women.”

National Park Service. “Mary Church Terrell.”

National Park Service. “1913 Woman Suffrage Procession.”

Noftsigner, Kate. “The 100 Year March: Celebrating Delta Sigma Theta and Alice Paul” (Ms. Magazine Mar. 5, 2013).

Parkinson, Hilary. “Suffering and Suffrage at the 1913 March” (National Archives Pieces of History Mar. 1, 2013).

VCU Libraries Social Welfare History Project. “Mary Church Terrell (1863-1954): Educator, Writer, Civil Rights Activist.”

Walton, Mary. “The Day the Deltas Marched Into History” (Washington Post Mar. 1, 2013).