Culture Changer

She moved to California from New York City for a change of scenery after a tragic loss and found solace camping under the desert sky. She fell in love with the strange beauty of the desert and made it her mission to persuade the country of the value of protecting it. She brought the desert to the city with garden exhibitions. and to the White House with photo albums. But it was her refusal to take no for an answer that made the biggest difference. Joshua Tree National Park is living proof of her success. Travel back in time to 1934 to meet Minerva Hamilton Hoyt…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

Minerva Hamilton Hoyt was furious. She had just finished reading the report on her proposal for a National Park northeast of Palm Springs, near the Little San Bernardino Mountains. Minerva had been working for years to persuade the public, California officials, and the National Park Service that desert landscapes and Joshua trees were just as deserving of protection as the redwood and pine forests in other national parks around the country.

Mural of Minerva Hoyt at Joshua Tree (NPS)

She hosted the report’s author, Yellowstone National Park Superintendent Roger Toll, in March 1934 for a three day tour of the one million acre proposed site. She knew that the stakes were high, as Toll had enormous power and his disapproval had killed other national park proposals. She designed the perfect itinerary and arranged for a local prominent botanist to join the tour to answer any question Toll might have about desert plant life. Unfortunately, the weather didn’t cooperate, and the tour ended with Minerva concerned that the cold and cloudy conditions had soured Toll on the desert.

The report in her hands confirmed her worries. In it, Toll rendered his verdict to the NPS Director: No Park. Toll had a few logistical concerns, but the biggest blow was his opinion that the desert was “lacking in any distinctive, superlative, outstanding feature that would give it sufficient national importance to justify the establishment of a national park.” He did acknowledge that the Joshua trees themselves were interesting and worthy of protection. This did little to cool Minerva’s anger, as he proposed protecting only a 138,240 acre grove, which was only 13% of the park.

Minerva vowed that Toll would not have the last word. She mapped out a strategy to achieve the impossible – get past a Toll “No.” She argued that Toll’s background made him less likely to recognize beauty that was so different from the traditional landscapes of Yellowstone. She asked for a second opinion from NPS Assistant Director Harold Bryant, who was a native Californian and a biologist. Bryant agreed that the Joshua Tree proposal was an important piece of desert worthy of protection.

Minerva vowed that Toll would not have the last word. She mapped out a strategy to achieve the impossible – get past a Toll “No.” She argued that Toll’s background made him less likely to recognize beauty that was so different from the traditional landscapes of Yellowstone. She asked for a second opinion from NPS Assistant Director Harold Bryant, who was a native Californian and a biologist. Bryant agreed that the Joshua Tree proposal was an important piece of desert worthy of protection.

While Bryant’s support cracked the door open, Minerva needed another push, and aimed for the ultimate audience, President Franklin D. Roosevelt. President Roosevelt was on a mission to create jobs to pull the country out of the Great Depression, and had decided to build more national parks.

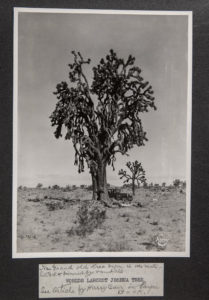

From Minerva’s Album (NPS)

Minerva knew she wouldn’t get the President to the desert, so she brought the desert to him. She hired a famous landscape photographer and created two photo albums filled with images of Joshua trees, cacti, flatlands leading into mountains, and a desert oasis. Minerva created panoramas by taping pictures side by side to illustrate the vastness of the land. She included newspaper articles for context and arranged for the black and white photos of desert flowers to be painted with their vibrant colors for maximum effect.

To ensure the albums didn’t get lost in a pile of correspondence, Minerva asked the California Governor to write a letter of introduction. She then asked the U.S. Chamber of Commerce President to hand deliver the albums, which he did in June 1934, reporting back to Minerva that the President “desired that I express to you his great appreciation of your kindness and of his intense interest in the work you are doing.” The albums worked. Minerva got the Toll “No” reversed, and on August 10, 1936, President Roosevelt established Joshua Tree National Monument.

The Power of the Wand

Minerva made Joshua Tree National Park happen because she inspired people to take another look at the desert and appreciate the non-traditional beauty it held. She became known as “Woman of the Joshua Trees” and “Apostle of the Cacti.”

In My Backyard is a Seattle based organization whose mission is to “connect communities to our backyards.” Its student driven program is designed to “nurture a sense of stewardship, appreciation and pride for National Parks and the nature and history we all share.” Each summer, teen interns work together to develop programs for park outreach and education. In My Backyard highlights the impact of their experience.

The National Park Service offers teens a variety of jobs, internships and volunteer opportunities. Many state and local park systems offer the same, like the Three Rivers Park District’s Teen Council in Minnesota.

Her Yellow Brick Road

Joshua Tree at sunset (NPS)

When Minerva moved to California in 1897, she was surprised by the beauty of the desert. While it was very different than the lushness of her childhood home in the deep south, she soon grew to love the varied textures of Joshua trees and cacti accented by splashes of wildflower color. She spent many nights camping under the stars.

The desert landscape of Devil’s Garden area near the Morongo Valley was a favorite spot of hers. She watched with horror as it was destroyed by landscapers pulling out its plantings for their own use. Other desert areas met the same fate. When she returned to her first desert campsite 30 years later, she found “a barren acreage with scarcely a Joshua tree left standing and the whole face of the landscape a desolate waste, denuded of its growth for commercialism.”

Minerva started speaking up and made a name for herself as a desert conservationist. In 1928, the California State Park Commission asked her to recommend land in southern California to be included on a list of potential state parks. After careful study, she authored the Commission’s report, listing her top three desert choices: Death Valley, the Red Rock Canyons in Anza-Borrego, and the Joshua Tree groves north of Palm Springs.

Minerva started speaking up and made a name for herself as a desert conservationist. In 1928, the California State Park Commission asked her to recommend land in southern California to be included on a list of potential state parks. After careful study, she authored the Commission’s report, listing her top three desert choices: Death Valley, the Red Rock Canyons in Anza-Borrego, and the Joshua Tree groves north of Palm Springs.

Minerva’s favorite was the one million acre Joshua Tree proposal, which extended from the Salton Sea to Twentynine Palms. Joshua Tree included all the variety she loved about the desert: Joshua Tree groves, huge cacti, big boulders, bright flowers, and the Mohave and Colorado River ecosystems. After writing the state report, her ambition for the land grew and she decided to pursue a National Park designation. The biggest hurdle was the absence of national demand to protect desert landscapes. The desert was scary and unknown to most people outside of the west, who thought of it as hot, flat, and barren. One early explorer described the Joshua Tree as “the most repulsive tree in the vegetable kingdom.”

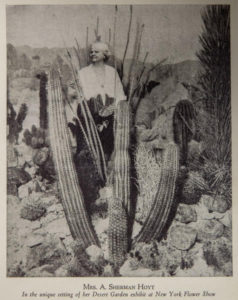

Since New York City, Boston, and London were the center of society, Minerva decided to bring the desert and all of its beauty to the people there. In New York, Minerva secured a spot in The Garden Club of America’s Flower Show. She filled seven freight cars with rocks, cacti, plants, and sand and sent them to New York via rail. She had desert flowers flown in from California twice a day, keeping them fresh in her hotel bathtub so she could continually restock the exhibit. She included taxidermied animals to correct the assumption that nothing lived in the desert.

Since New York City, Boston, and London were the center of society, Minerva decided to bring the desert and all of its beauty to the people there. In New York, Minerva secured a spot in The Garden Club of America’s Flower Show. She filled seven freight cars with rocks, cacti, plants, and sand and sent them to New York via rail. She had desert flowers flown in from California twice a day, keeping them fresh in her hotel bathtub so she could continually restock the exhibit. She included taxidermied animals to correct the assumption that nothing lived in the desert.

She sent the desert across the Atlantic on a ship and set up similar exhibits in London. Police officers had to guard the cactuses from crowds who wanted to touch them. Even Princess Mary visited to see what the excitement was about. The exhibits were a success. One of Minerva’s most important converts was William Jardine, President Coolidge’s Secretary of Agriculture. He was impressed that she “succeeded in bringing the West to the East.”

Desert Exhibition

When Minerva returned to California, she founded the International Desert Conservation League in March 1930. One of the League’s first acts was to ask the NPS Director to consider establishing a Joshua Tree National Park. She was disappointed with the initial response, which was that he was focusing on desert projects elsewhere. Later that summer, a vandal set fire to an 80 foot Joshua tree, completely destroying it. Minerva offered a $100 reward to find the arsonist and used the senseless destruction to build more support for conservation, commenting that “the old giant will not have been sacrificed in vain if we can stimulate the public imagination to a definite program for the conservation of those remaining.”

Over the next few years, she strategically invited prominent people to be honorary vice presidents of the League, including museum directors, university presidents, and the founder of the U.S. Forest Service. Minerva put her skills as a hostess to good use, using teas and garden parties as her main tools for outreach.

When President Roosevelt took office in 1933, one of his plans to create jobs was to establish more national parks. Minerva was able to get a meeting with Secretary of Interior Harold Ickes that summer to share her vision for Joshua Tree. He told her that “The President is for it and I am for it” and reserved 1.136 million acres to study for the proposed park. The next step was a site visit from Roger Toll.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Minerva was born on a Mississippi cotton plantation into a wealthy family. She studied at music conservatories and attending finishing school. When Minerva married Dr. Sherman Hoyt, she moved with him to New York City. Their only son died when he was a baby. The grieving parents decided they needed a change of scenery and moved across the country to South Pasadena, California. On the train west, Minerva spent most of the time watched the changing landscapes out of the window and got her first glimpse of the beauty of the west.

In Pasadena, Minerva spent hours tending her 5 acre garden, reveling in the discovery of the different plants that grew in the California climate. She cultivated it with skill and flair and it was featured in a Forbes Magazine list of the 14 most important gardens in the country.

She took frequent trips out to the desert, and often camped there overnight. She was moved by her experiences there: “during nights in the open, lying in a snug sleeping bag, I soon learned the charm of a Joshua Forest. … Above, the bright desert constellations wheeled majestically toward the west, a timepiece for the wakeful.”

When she wasn’t in the garden or desert, Minerva enjoyed working in her community. After Sherman died in 1918, her charitable activities were a lifeline. She organized Red Cross blood drives, was president of the Los Angeles Symphony Orchestra and the Boys and Girls Club of Los Angeles, and was one of the founding members of the Valley Hunt Club, which started the Tournament of Roses Parade.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- Minerva was born in Durant, Mississippi on March 27, 1866.

- In 1931, the President of Mexico invited Minerva to visit and make recommendations for parks and reserves. As a result of her work, he set aside a 10,000 acre cactus forest and named a species of cactus after her: the Mammillaria hamiltonhoytea.

- A copy of one of the photo albums Minerva sent to President Roosevelt is kept in the Joshua Tree National Park archives.

- The Joshua Tree National Monument Proclamation encompassed 825,340 acres – over 80% of Minerva’s initial proposal and 7 times more than Toll’s report. The other 20% was primarily owned by Southern Pacific Railroad, who refused to sell. Minerva asked for and secured a promise from NPS that it would keep trying to acquire that land.

- Mining interests opposed the Park because new mining claims would not be allowed. Minerva died on December 15, 1945 at age 79 and Joshua Tree lost one of its most passionate and influential advocates. In 1950, Congress reduced it by almost a third, allowing mining in 289,500 of its acres.

- The Joshua Tree headquarters was built on 58 acres of donated land, which included the Historic Oasis of Mara in Twentynine Palms.

- The Joshua Tree National Monument dedication ceremony took place on April 7, 1954.

- The land given to miners was returned in 1994, just before Joshua Tree National Monument became Joshua Tree National Park.

- In 2012, the National Park Service renamed one of the Park’s mountains for Minerva: Mt. Minerva Hoyt.

- The park didn’t attract many visitors in its first years, but has recently grown in popularity. A record number 2.99 million people visited in 2019.

- There is a mural featuring Minerva in the Joshua Tree Visitors Center.

- The area is still under threat. Vandals destroyed many of the Joshua trees during the 2019 Government shutdown. There are pressures to build big industrial projects near its boundaries.

- The Minerva Hamilton Hoyt Desert Conservation Award awarded annually by the Joshua Tree National Park Association to honor work in desert preservation.

Want to Know More?

Zarki, Joseph W. Joshua Tree National Park (Arcadia Publishing Co. 2015)

Conrad. Tracy. “How Minerva Hamilton Hoyt Saved Joshua Tree National Park For Future Generations” (Desert Sun, May 13, 2009).

National Park Service Staff. “Minerva Hamilton Hoyt” (NPS.gov Dec. 21, 2017)

Netburn, Deborah. “How A South Pasedena Matron Used Her Wits and Wealth to Create Joshua Tree National Park” (Los Angeles Times Feb. 14, 2019)