Super Scientist

She decided to open an entirely new chapter in her life at age 51 by going back to college to become a botanist. She spent the next 17 years traveling from Alaska to the Amazon by ship, auto, donkey, and foot, exploring and sending over 145,000 plants home to be studied and classified. Her discoveries are still being studied by scientists today. Step onto a 1926 steamer ship coming into port and meet Ynes Mexia…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

Ynes Mexia stood on the deck of a steamer ship pulling into the port of Sinaloa, Mexico. It was a beautiful September day in 1926, and it had been a long trip from her home in San Francisco. Ynes was anxious to begin her first solo adventure as a botanist. At age 56, Ynes was older than most travelling scientists, but she was used to it. She had started taking botany college classes only four years before with students young enough to be her children.

Ynes in the field (California Academy of Sciences)

Botany, the science of plants, was a newly booming field. Humans use plants for all of life’s necessities, including oxygen, food, medicine, clothing and shelter. As the healing and functional power of plants was becoming more known and understood, botanists were traveling the world collecting plant specimens. The specimens were sent home to herbariums (“plant libraries”) where they were sorted, labeled and stored for future study.

Ynes had travelled to Mexico with a group from Stanford University’s Dudley Herbarium the year before. She had grown restless because she wanted to follow her own scientific instincts, and not be limited to the expedition itinerary. Ynes was fluent in Spanish and was confident she would be able to navigate on her own. Ynes had to decide whether her urge to explore was greater than her need for society’s approval or the promise of safety. Women were discouraged from traveling without a man to protect them (a married woman could only get her own passport if her husband approved). Ynes chose to leave and follow her own path. Unfortunately, this path led to a fall off a cliff while reaching for a plant. She broke several bones and had to return to California to recover.

Ynes spent her rehabilitation planning a return to Mexico to resume her work. She mapped out an itinerary traveling between several geographic areas in Mexico via train and boat, including Mazatlan, Nayarit, Puerto Vallarta, and San Sebastian. She made plans for setting up a base camp in each town, which included finding a local guide to ride into the mountains with her each morning to explore and collect new specimens. She made lists of the equipment she needed: presses, dryers, papers, notebooks, cameras, and two 75 pound mule boxes to carry these supplies into the field and back to base camp. She studied to prepare for long evenings of pressing and cataloguing what she had collected each day.

Successfully launching an expedition required lots of money in addition to this careful planning. Ynes would earn the standard rate of 20 cents per specimen once she started collecting, but she needed to pay for supplies and her initial travel expenses before she left. She took a creative approach by contacting other botanists and offering to send them some of the specimens from her expedition in exchange for supplies now.

As her ship finally docked in Sinaloa, Ynes gathered her belongings and got in line to disembark. When she walked off the boat, she moved forward into her life as an independent woman and scientist. Ynes would end up collecting nearly 33,000 specimens on this expedition and share them with herbariums around the world. When she returned to San Francisco, she resumed college botany classes to gain more knowledge for her work, but a degree wasn’t her goal (she never got one). She spent the rest of her life traveling to places that hadn’t been explored by botanists before, collecting plants, and returning home to give lectures and write articles about her discoveries.

The Power of the Wand

Ynes’ scientific career spanned only 13 years, but she accomplished more than many scientists do in a lifetime. She collected 145,000 plant specimens, which are in herbariums across the United States and Europe. Botanists are still reviewing and classifying the specimens she collected. The contributions of many women scientists of her era remain hidden because they were encouraged to be modest. Ynes saw no need to downplay her accomplishments, pointing out if men were naming their discoveries after themselves, women should too. Ynes discovered around 500 new species of plants, 50 of which are named after her.

Today, Ynes’ legacy lives on in young women who are combining their love of travel, adventure and science to build a career in botany. One of them is Roxi Steele, a Ph.D. student in plant biology at the University of Texas. Roxi was a mechanical engineer when she took a summer college course called “Race to Save the Planet.” That class inspired her to volunteer for an Earth Watch project helping scientists in the Costa Rican rain forest That trip inspired her to be a scientist working to conserve the rain forests. She went back to school and now spends much of her research time in Caribbean rain forests. Like Ynes, she returns home periodically to share her discoveries with other scientists, policy makers, and students.

Her Yellow Brick Road

Ynes was studying botany at the University of California, Berkeley, when she decided to take some additional summer classes at the California Academy of Sciences. One of the first people she met there was famed botanist Alice Eastwood. Alice led field trips to the Sierra Nevada and the coast where she taught students how to collect and preserve viable plant specimens for future study. There are millions of different types of plants in the world, and botanists have designed a classification system to sort them. These classifications are critical to identify and predict how plants will behave in different environments and applications. Botanists collect several samples to study any differences between them, and often return to the same area in multiple seasons to observe how the plant changes with the weather.

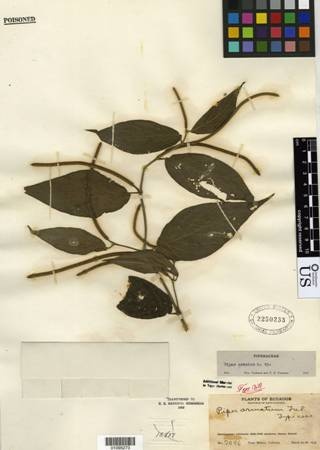

One of Ynes’ specimens. (Smithsonian Museum of Natural History)

Alice became an important friend and mentor, teaching Ynes that botany takes patience, care, and time. Ynes learned how to carefully remove a plant from the earth to ensure that every part of it, including the roots, attached leaves, and flower or fruit, stays attached. She practiced pressing each plant between two sheets of special paper to remove moisture to prevent mold or crumble. Ynes later spent so much time in rain forest climates that she became an expert at drying samples. Finally, Ynes learned how to take photos and make detailed field notes to identify where and when each specimen was collected. Ynes took to heart the lesson that if a botanist did everything right during collection, her plant specimens could last forever.

Ynes was inspired by her experiences on Alice’s field trips to say yes to any similar opportunities that came her way. She went on a short collecting trip to Mexico led by a Berkeley paleontologist. She spent a summer at the Hopkins Marine Station in Pacific Grove, California. From there she applied for a spot in the Stanford/Dudley Herbarium expedition to Mexico and was accepted. This was Ynes’ first foray into the big leagues, as Dudley was one of the country’s leading plant collections.

Botany Expedition 1923 (California Academy of Sciences)

Before Ynes left for the Stanford trip, she wrote to Alice, offering to collect double specimens to send to her. Ynes collected and catalogued 500 different plants with the Stanford group. She even discovered a new one, which was named “mimosa mexia” in her honor. As Ynes gained more confidence in her knowledge and skill, she wanted to follow her own research path. She spent several sleepless nights weighing the risks of striking out on her own against staying with the Dudley group.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Ynes had a turbulent childhood. She was born in Washington D.C. while her dad, who was a diplomat from Mexico, was stationed there. Her parents got divorced when she was 3. Her dad returned to Mexico and her mom moved the rest of the family to a ranch in Texas. Eventually the family moved back to her mom’s native Pennsylvania, and Ynes spent her teen years in boarding schools in Philadelphia, Canada, and Maryland.

After Ynes graduated from high school in 1887, she moved to Mexico City to help care for her dad, who was very ill. She devoted much of her young adult life to caring for him and raising poultry and other animals on their ranch. In 1897, she married a local merchant but continued to care for her dad until he died a year later. Her dad’s mistress and illegitimate children contested his will, and Ynes had to spend years in court fighting to keep the ranch. She finally prevailed, only to endure her husband’s death in 1904. Ynes was lonely, and a few years later married one of her employees. This marriage was a disaster — her husband’s bad business decisions bankrupted her ranch and Ynes struggled with depression.

Ynes needed a fresh start, so decided to divorce her husband and move back to the United States. She was 38 years old, with no family, no job, and the freedom to choose anywhere in the country to start over. She settled in San Francisco and found work as a social worker. She spent as much time as she could outdoors because it boosted her spirits.

Ynes needed a fresh start, so decided to divorce her husband and move back to the United States. She was 38 years old, with no family, no job, and the freedom to choose anywhere in the country to start over. She settled in San Francisco and found work as a social worker. She spent as much time as she could outdoors because it boosted her spirits.

She joined the Sierra Club and the Save The Redwoods League and began hiking with her Sierra Club friends all around northern California. As the years went by, Ynes wanted to know more about the plants growing along the trails that provided her with so much peace and beauty. She enrolled at the University of California at Berkeley to study botany when she was 51.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- Ynes was born in Washington, D.C. on May 24, 1870.

- Ynes discovered two entirely new genre of plants: the Spumula quadrifida Mains (Pucciniaceae) and the Mexianthus mexicanus Robinson (Asteraceae). Both are Mexican flowering plants in the sunflower family.

- Ynes was 58 when she became the first botanist to collect plants in what is now known as Denali National Park in Alaska. The conditions were brutal, even for summer, and she traveled primarily by sled dog. She and the dogs got stranded in a huge September snowstorm and after they were rescued, she returned home.

- Ynes planned an expedition to the Amazon River when she was 61. She secured visas for Brazil, Columbia, Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia so she could follow whatever path she desired without worry about crossing borders.

- Once there, Ynes spent 24 days on a steamer ship traveling the entire length of the Amazon from Brazil to its source in the Andes Mountains. She spent the next 2+ years collecting over 65,000 specimens while traveling between sites primarily by balsa raft and canoe.

- Soon after Ynes returned from the Amazon, she and two other botanists drove an open roof Model T Ford around California, Nevada, Utah and Arizona collecting plants.

- Ynes heard about a tree called the wax palm, which could thrive at higher altitudes and in colder weather than most palms, making it a good fit for California. She designed an expedition to Ecuador on behalf of the Department of Agriculture to find it. She was 64.

- To find the wax palm, Ynes and her companions had to hike up a mountain to reach the treeline. It was a long hike in oppressive heat. They were close to their destination when temperatures dropped and a torrential rain began. Most of the team wanted to return to base camp. Ynes worried that if they turned back, she would never get this close to the wax palm again. She convinced her team to stay by building a shelter from pack rope, ponchos, wild grasses, and leaves. Ynes made them all stew from her canteen water, potatoes, and pea soup powder. With shelter and a meal, they waited out the storm, and were able to find the wax palm.

- While Ynes sent most of her specimens to the California Academy of Sciences, herbarium collections around the world include her work.

- Ynes provided funds to naturalist Vernon Bailey for his humane animal trap invention.

- Ynes was diagnosed with lung cancer during an expedition in Mexico. By the time it was discovered, it was very advanced and she died a few months later, on July 12, 1938.

- Part of Ynes’ estate was given to the Save-the-Redwoods League, which used it to purchase land in northern California, including a beach and Home Creek Canyon.

Want to Know More?

Mexia, Ynes, “Botanical Trails in Old Mexico — The Lure of the Unknown.” Madrono, vol. 1, no. 16, (1929), pp. 227-38. Retrieved at www.jstor.org/stable/41421925.

Bonta, Marcia Myers, Women In The Field: America’s Pioneer Naturalists

Floy Bracelin, “The Ynes Mexia Botanical Collection,” an oral history conducted 1965 and 1967 by Annetta Carter (Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley 1982)

Downs, Winfield Scott. Encyclopedia of American Biography, Vol. 11 (The American Historical Company 1940)

From the Stacks. “Archives Unboxed: Ynes Mexia” (California Academy of Sciences Jan. 6, 2014)

Kiernan, Elizabeth. “Late Bloomer: The Short, Prolific Career of Ynes Mexia” (Steere Herbarium, NY Botanical Garden Feb. 26, 2015)

Polk, Milbry, Tiegreen, Mary. Women of Discovery: A Celebration of Intrepid Women Who Explored the World (Clarkson Potter Publishers 2001).

Radcliffe, Jane. Ynes Mexia 1870-1938 (California Academy of Sciences)

Yount, Lisa. A Biographical Dictionary A to Z of Women in Science and Math (Facts on File, Inc. 1999).