Passionate Patriot

Her dream was to be a diplomat, but as a woman with a disability – she lost a leg in a hunting accident – she was passed over by her State Department bosses time and again. But when World War II broke out, she proved how resourceful she could be, using her wireless radio to provide intelligence to Allied forces, coordinate the French Resistance, and pave the way for D-Day. She risked her life every time she turned on her radio and quickly became one of the Nazi regimes most wanted spies. Sail back to 1944 and join Virginia Hall as she sneaks into France to lay the groundwork for the D-Day invasion…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

As a boat silently slid towards the French shore in the moonlight, an elderly peasant woman climbed out of a boat and waded to the beach with an old battered suitcase under her arm. But appearances were deceiving — Virginia Hall was only 38 years old and her suitcase held a new state-of-the-art wireless radio. It was March 21, 1944, and she was sneaking into war-torn France as a spy for the Allies.

“Les Marguerites Fleuriront ce Soir” by Jeffrey W. Bass, 2006 (CIA)

Virginia was thoroughly committed to her disguise — she filed her teeth down to look older, dyed her hair gray, created wrinkles with makeup, and padded her clothes to look heavier. She also shuffled her feet to disguise the constant limp from her prosthetic leg. The “Limping Lady” was already well known to Nazis. In fact, she was one of the most wanted Allied spies by the Gestapo. If she was caught, she would be put to death.

Virginia’s mission was to lay the groundwork for D-Day. She headed to southern France to organize the French Resistance in the area. At the time, it was merely a loose network of rebel groups. They had little leadership, conflicting agendas, poor equipment and virtually no training. Virginia’s goal was unite them into a force that could support the Allies.

In exchange for a roof over her head, Virginia worked odd jobs for various farmers — milking cows, making cheese, selling produce, and tending goats. Her cover was perfect, since it allowed her to roam the countryside and gather information.

Virginia scouted German troop numbers and movements. She mapped out supply routes and infrastructure. She identified parachute drop sites. She organized resistance cells and trained men. Before long, help arrived from the sky. The British dropped supplies by parachute — weapons, ammunition, batteries, bandages, clothes, soap, money, bicycle tires, and more wireless radios.

Virginia receives the Distinguished Service Cross, 1945 (CIA)

Most evenings, Virginia set up her wireless radio in the attic of her house and transmitted all she had learned to London. After establishing a connection, she sent and received messages through the radio by morse code. Virginia risked her life every time she used her wireless radio. The Germans knew someone had a radio in the region and worked furiously to track her signal and determine her location. But Virginia was never caught.

Things became tense as D-Day approached. Virginia tuned into the BBC broadcast on the radio every day, listening for code words and messages. Finally, she heard it — D-Day was happening. All her planning had led to this day. It was time to act.

Virginia barely ate or slept for days. She traveled the countryside on her bicycle and ordered Resistance groups to carry out pre-arranged acts of sabotage. They cut telephone lines and electricity wires. They destroyed railroad tracks and bridges. They took down road signs and changed the names of streets. They attacked supply caravans. In short, they threw the German troops into chaos and prevented reinforcements from reaching the beaches of Normandy.

What Virginia accomplished in southern France was nothing short of remarkable. Later, President Eisenhower would say that the actions of the French Resistance probably shortened the war by about 9 months. And Virginia was a key part of it all. Her courage knew no limits.

The Power of the Wand

Virginia Hall was one of the most valuable spies for the Allied forces during World War 2. She took advantage of societal prejudices of the day — most people thought a woman wasn’t tough enough to be a spy. But she had what it took, and then some. Her efforts and abilities surpassed everyone’s expectations and her success opened the doors to more women agents in undercover operations.

Her Yellow Brick Road

After Nazi Germany took over France during World War 2, Virginia was forced to flee Paris. She was determined to help the French fight back, however. Her chance came while traveling to London. Virginia met a man who was part of the Special Operations Executive (SOE), a new secret department of the British armed services. And he recruited her — before she knew it, Virginia was a British spy.

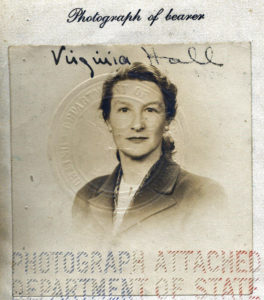

Virginia’s passport photograph (Smithsonian Institute, Lorna Catling Collection)

Virginia returned to France as Agent 3844 of the SOE. Her cover was being an American reporter for the New York Post, sent to cover the Vichy government. She embedded all intelligence that she gathered in the “stories” that she filed (they were sent to London rather than New York City). And the SOE was thrilled with the information that poured through her articles.

Her cover fell apart when America entered the War after Pearl Harbor. So she moved to Lyon to help the resistance. Virginia developed a spy network and gathered information from the region. She recruited loyal informants, established safe houses, hired document forgers, trained couriers, helped Allied airmen escape to safety, and smuggled information through the American embassy in Switzerland. Her most risky operation, however, was to help her fellow SOE agents escape from prison.

Virginia was careful — she changed her appearance, name, routine, and location frequently. After a few months, however, Virginia was in serious danger. The “Limping Lady” was one of the most wanted people in all of France. Cars followed her and people in her network were arrested. The Gestapo was closing in. So Virginia decided it was time to escape.

Virginia was careful — she changed her appearance, name, routine, and location frequently. After a few months, however, Virginia was in serious danger. The “Limping Lady” was one of the most wanted people in all of France. Cars followed her and people in her network were arrested. The Gestapo was closing in. So Virginia decided it was time to escape.

She took a train south and arranged for a guide to bring her on foot across the Pyrenees to Spain. It was a difficult journey, especially with a prosthetic leg. She was in complete misery. But she kept going towards freedom.

Virginia made it to Spain and boarded a train to Barcelona — only to be arrested for having improper paperwork. While in prison, she smuggled out a coded message to the American consulate. They sprang to action and rescued her. After a hot bath and a good night sleep, she was on her way back to London.

Virginia was the only SOE agent to serve behind enemy lines for over one year. And she wanted to return, but SOE leadership decided it was to dangerous to send her on another mission. So Virginia requested a transfer to the new American spy department, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). With her experience, it was an offer the OSS couldn’t refuse.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Virginia was born into a wealthy family in Baltimore, Maryland. Her family’s fortunes were dwindling, however, and her mother hoped that Virginia would help the family by marrying a wealthy man. At first, Virginia complied with her mother’s wishes and became engaged at age 19. But she had other dreams that she couldn’t ignore — she wanted adventure; she wanted to explore the world; and she wanted a job. So she called off the engagement and went to college.

Her studies eventually took Virginia to Paris. She fell in love with France and finally felt free to be herself. She returned home a new person in 1929 and pursued a graduate degree at George Washington University.

Virginia’s Department of State Identification Card

Virginia went abroad with the State Department, as a secretary at the American embassy in Warsaw. She felt that her talents were being wasted behind the desk, however. So she applied to become a diplomat, but wasn’t accepted. Frustrated, Virginia transferred to the American consulate in Turkey and hoped it would be a better position.

While stationed in Turkey, Virginia’s life took a drastic change — she was hunting with friends and accidentally shot her own foot. She slipped into unconsciousness and lost a lot of blood. Her friends threw her in the car and raced to the hospital. Unfortunately, infection set in and her left leg was amputated in a last ditch effort to save her life.

Virginia was eventually fitted with a prosthetic leg, which was made of wood and held in place with leather straps (she named it “Cuthbert”). It was heavy and painful, and she walked with a limp for the rest of her life.

Virginia didn’t let her new disability slow her down. She returned to work and was stationed in Venice. It was a difficult city for her to navigate, but she refused any special treatment. In fact, she worked harder to prove she was still up to the job.

Then, World War 2 began and Europe changed overnight. Virginia resigned from the State Department and volunteered to drive ambulances for the French 9th Artillery Regiment. She kept her disability a secret and embraced her chance to serve on the front lines.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- Virginia was born on April 9, 1906 and grew up with her older brother, John, in Baltimore. Her mom, Barbara, had been a secretary and her dad, Ned, was a wealthy banker. The family lost almost everything in the stock market crash of 1929. Then, Ned died of a heart attack in 1931.

- Virginia studying at 6 different universities: Radcliffe College, Barnard College, American University, Ecole Liver feis Sciences Politiques in Paris, Konsular Akademie in Vienna, and George Washington University. She learned 5 languages along the way.

- Virginia worked for the State Department in various posts around the world. Then she resigned in 1939, after 10 years of service.

- During World War 2, Virginia worked for the Special Operations Executive, a secret division of British intelligence. She became such a valuable asset that the American intelligence agency, Office of Strategic Services, eventually hired her. In total, she spent 6 years in war-torn France.

- Virginia was awarded America’s second highest military honor, the Distinguished Service Cross, on February 5, 1946.

- France awarded Virginia the Croix de Guerre with Palm for heroism in combat on September 27, 1946.

- After World War 2, Virginia became one of the first women to work at the new-created CIA in Washington DC. She was hired as a desk operative, but really wanted to be a field agent. She was passed up for promotion after promotion and finally retired in 1966.

- Virginia married Paul Goillot, a fellow operative from France. Her mother didn’t approve of the relationship, however, so she kept it a secret from her family for over 10 years. They finally married in 1957.

- Virginia died on July 8, 1982, in Maryland at age 76.

- Years later, Virginia finally received the recognition she deserved within the CIA. In 1988, her name was posthumously added to the Military Intelligence Corps Hall of Fame. In 2016, the new Virginia Hall Expeditionary Center building at the CIA was named in her honor.

Want to Know More?

Activity Report of Virginia Hall; 9/30/1944; Records of the Office of Strategic Services, Record Group 226. (Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/activity-report-of-virginia-hall, August 9, 2021)

Elder, Greg. “Faces of Defense Intelligence: Virginia Hall – The “Limping Lady.” Defense Intelligence Agency, October 27, 2016.

Lineberry, Kate. “WANTED: The Limping Lady. The intriguing and unexpected true story of America’s most heroic—and most dangerous—female spy.” Smithsonian Magazine, February 1, 2007.

Pearson, Judith. The Wolves At The Door: The True Story of America’s Greatest Female Spy. Guilford, CT: Lyons Press, 2008.

Purnell, Soina. A Woman of No Importance: The Untold Story of Virginia Hall, WWII’s Most Dangerous Spy. New York City: Viking , 2019.