Inspiring Inventor

She was a kid who loved math and science, but whose parents and teachers told her those subjects weren’t for girls. She persevered, and after studying physics and math at college, got a job at NASA writing computer programs – even though she had never seen a computer in real life before being hired! Her passion was turning data collected from space in into images to be studied and enjoyed. She used these skills to invent an Illusion Transmitter that could send 3D illusions from one location to another in real time! Take a stroll through a 1976 scientific conference where the light bulb of invention literally went on for Valerie Thomas…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

On an otherwise ordinary day in 1976, Valerie Thomas walked past a scientific exhibit at a conference she was attending and stopped in her tracks. What she saw reminded her of being a young girl fascinated by the science behind optics and images. She had spent countless hours of her childhood watching her dad take apart the family television and develop photographs. Her passion for figuring out how to use machines to create images was driving her current work at NASA. She had spent the last 6 years successfully developing an image processing system for the Landstat satellites, which were the first satellites that could take pictures of Earth from Space.

Valerie (NASA)

Valerie examined the exhibit more closely. It featured a lamp with a glowing lightbulb, but the lightbulb wasn’t real – it was a 3 dimensional illusion. The scientist had created the illusion by attaching an additional light socket just below the regular socket, facing upside down. He had screwed a real light bulb into the upside-down socket, and positioned a concave mirror behind the bulb. The concave mirror curved inward and the bulb was centered on the inside of the curve. The concave mirror projected the reflection of the light bulb outward, in front of the mirror, which made it seem real. The lamp and mirror were positioned to line up the bulb’ reflection with the lamp’s upright lamp socket, making it look like the lamp was lit.

Valerie was intrigued by the possible applications of the exhibit. She had been up to the challenge at NASA to figure out how to translate data sent from a satellite into images that could be printed on Earth. She was curious as to whether she was up for the challenge of transmitting a 3D image of an object, like the lightbulb in the exhibit, to another location in real time.

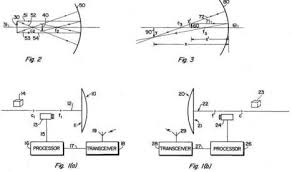

Valerie returned to her lab and started designing experiments with illusions. She studied how when an object is placed in front of a concave mirror, the human eye combines the two reflections created into a single 3D image. She observed how changes to the size and position of the mirror affected the illusion. She experimented with placement of the object, as well as the amount and angle of light to create the best reflection. She worked with parabolic mirrors, which are made in a precise shape to ensure that any spot on the mirror is equal distance from the mirror’s focal point. The parabolic shape minimized the image distortions.

Valerie returned to her lab and started designing experiments with illusions. She studied how when an object is placed in front of a concave mirror, the human eye combines the two reflections created into a single 3D image. She observed how changes to the size and position of the mirror affected the illusion. She experimented with placement of the object, as well as the amount and angle of light to create the best reflection. She worked with parabolic mirrors, which are made in a precise shape to ensure that any spot on the mirror is equal distance from the mirror’s focal point. The parabolic shape minimized the image distortions.

Valerie’s efforts culminated in the Illusion Transmitter – a device that can create, transmit, and receive 3D images of an object in real time. At the transmission site, light and a concave parabolic mirror are used to create an independent 3D image of an object. An image detection system converts the 3D image into video signals and transmits them by cable or electromagnetically to a receiver at a remote site.

Patent Drawing for the Illusion Transmitter 1980 (USPTO).

The receiver translates the signals and sends the image to a projector, which projects the image onto another parabolic mirror to create the 3D illusion. With this invention, Valerie made it possible to create an optical illusion and send it to someone far away, who would see the same image in real time.

Valerie applied for a patent for the Illusion Transmitter, on December 28, 1978. The patent was issued on October 21, 1980.

The Power of the Wand

Like Valerie, 21 year old Alexis Lewis has been curious about the world since she was little, and considers herself (and everyone!) to be natural born inventors. At age 15, Alexis was granted a patent for her invention, the “Rescue Travois,” a bamboo emergency stretcher. She has another patent pending for the “Emergency Mask Pod,” which is a device intended to get oxygen to people in an emergency situation. Alexis is an advocate for adding Inventing 101 classes to Middle School curriculum around the country. Visit Alexis and learn more about her inventive life at www.alexislewisinventor.me.

Her Yellow Brick Road

The first time Valerie ever saw a computer in person was in 1964, on her first day of work at NASA’s Goddard Space Center, located in Greenbelt, Maryland. Before then, she had only seen computers in science fiction movies. She had to learn quickly, because part of her job description was writing computer programs! Her math background helped her, as she understood abstract algebra and how to work with different number systems, all of which were necessary for programming.

Valerie spent her first six years at NASA working for the Orbiting Geophysical Observatory (OGO). There were no communication satellites that could directly transmit data from space to Earth, so Valerie had to download data from space when OGO’s satellite was within antenna range. She then had to write a computer program to translate that raw data into a format the OGO could understand and analyze. There wasn’t a computer at her desk – she went to a separate building and used key punch cards to input her programs into the office computer.

Valerie spent her first six years at NASA working for the Orbiting Geophysical Observatory (OGO). There were no communication satellites that could directly transmit data from space to Earth, so Valerie had to download data from space when OGO’s satellite was within antenna range. She then had to write a computer program to translate that raw data into a format the OGO could understand and analyze. There wasn’t a computer at her desk – she went to a separate building and used key punch cards to input her programs into the office computer.

Valerie’s next assignment was as a member of the Landstat team. Landstat was NASA’s first satellite capable of taking pictures of Earth. It was exciting for scientists to have access to big picture views of Earth from thousands of miles up, and NASA needed a new digital image processing system that could “develop” images from the Landstat “camera.” Valerie moved to Michigan in 1970 to join a NASA team working on new Landstat software.

Landstat Satellite Above Earth (Goddard Space Center)

Landstat was able to “see” more than the than the human eye, and the data transmitted included infrared “false colors” representing features like heat, land cover, and vegetation. Valerie’s challenge was to write a computer program to translate Landstat’s complex raw data– much of which was in a high level mathematical format – into patterns and maps that scientists could use. The computer languages she knew made things too complicated, so she taught herself a new one, Fortran. She used it to write a simple program that could: 1) read the digital tapes in the required format and 2) print out the contents in an easy to read format.

Valerie built the bridge between the digital and visual representations of Landstat data, and scientists ran their data through Valerie’s program to make sure the data they were using matched the images they were seeing. The process was nicknamed “the ValDump,” and soon scientists from all over the world were asking for Valerie’s help. She published a guidance document which became the Landstat bible.

Valerie with Landstat Data Files in 1979 (NASA)

Landstat was so successful that it revolutionized research on Earth’s resources. The Large Area Crop Inventory Experiment (LACIE), which envisioned using Landstat images of wheat fields for global crop monitoring, was the next step. Valerie’s boss asked her if small test sites could be pulled out of a Landstat digital image. She said yes and NASA gave her a 50 person team and a 5 month goal: produce 100 test sites a day in fields around the world, covering the exact same areas every day. It was an ambitious project: when she asked a contractor for help with the program, he said she was asking the impossible. She responded with “I know… How long will it take to do it?”

Valerie’s test data was sent to the Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. Marshall’s old hardware could only handle processing 10 sites per day. After new hardware to support the 100 site goal arrived, Marshall scheduled a Readiness Review Meeting. Valerie was asked to go as Goddard’s representative. She agreed, thought she was a small part of a big meeting, and put together a 15 minute talk. When she arrived, she discovered the meeting was in a huge auditorium filled with representatives from multiple agencies – and she was on the agenda for a 45 minute presentation! The audience was full of questions, most of them from Robert MacDonald, head of LACIE, who sat in the middle of the front row.

His last question was: “Is Goddard ready to support launch?” Valerie looked him straight in the eye and answered “Yes.” When she got back to work, she called the colleague who had sent her to the meeting and said “You threw me to the wolves.” His response: “I know, but I knew you could handle it!”

Brains, Heart & Courage

Valerie was one of those kids whose curiosity led her to ask “how does this work” about every gadget she came across. It was an exciting time to be interested in science, as it felt like new technology was being rolled out every day.

Valerie inherited her scientific curiosity from her dad, who liked to work with electronics. The family had a large television that he would tinker with in his free time. When he took its back off and Valerie saw all the mechanical parts inside, she wanted to know how those parts made a picture on a screen. Her dad also developed his own photos, and Valerie was fascinated by how a photo enlarger worked to make an image bigger or smaller on photo paper with just a few adjustments. However, while her dad let her watch him work, most of her questions about what he was doing went unanswered. He, like many people at the time, believed science should be reserved for boys and men.

Valerie found the same resistance at school from her teachers – she was encouraged to focus on more feminine subjects. She resisted this advice the only way an 8 year old could – she went to the local library, found a book called The Boy’s First Book of Radio and Electronics, and brought it home. She hoped to work on the projects in the book with her dad, but he refused.

Valerie found the same resistance at school from her teachers – she was encouraged to focus on more feminine subjects. She resisted this advice the only way an 8 year old could – she went to the local library, found a book called The Boy’s First Book of Radio and Electronics, and brought it home. She hoped to work on the projects in the book with her dad, but he refused.

Things didn’t change in high school. It was an all-girls school that offered a few higher level math classes and barely any science. There were no opportunities for Valerie to learn more about electronics. It was assumed that girls wouldn’t (and shouldn’t) be interested in those subjects. Complicating matters even more, Valerie’s school had only recently been integrated. She was among the first Black students, and she wasn’t on the radar for advanced math classes.

Valerie was determined that college would be different. She applied to Morgan State University in Baltimore. Once accepted, she registered for as many math and sciences classes as she could. She found her home in the Physics Department, where she was one of only two women in her class to choose it as a major. She found supportive professors who encouraged her. She completed her physics degree and got close to a double major in math. After graduation, Valerie looked for a job where she could continue learning and doing what she loved. She applied for a position as a math/data analyst at NASA.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- Valerie Thomas was born in February 1943 in Maryland.

- Valerie spent eleven years, from 1970-81, as a member of the International Landsat Ground Station Operators Working Group. She was at NASA Headquarters from 1975-76 as a Landstat Assistant Program Manager. She then returned to Goddard to work on a Thematic Mapper sensor and the Pilot Land Data System.

- Valerie joined NASA’s Space Science Data Center (NSSDC) in 1985 as a Computer Facility Manager. She oversaw the consolidation of two computer facilities and was in charge of establishing structure and technology for the new entity.

- After her success at NSSDC, in 1986, NASA asked Valerie to serve as a Space Physics Analysis Network (SPAN) Project Manager. NASA wanted to restructure SPAN to give it a bigger reach. Valerie led the transition, and during her four years there, SPAN went from a 100 computer node network to 2700 computer nodes worldwide.

- Valerie also conducted research for NASA relating to the ozone layer, satellite technology, and Halley’s Comet. She also managed the NASA Automated Systems Incident Response Capability.

- Valerie retired in 1995 as the Associate Chief of NASA’s Space Science Data Operations Office (SSDOO). She also chaired SSDOO’s Education Committee.

- Valerie was awarded the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center Award of Merit and the NASA Equal Opportunity Medal.

- Throughout her career, Valerie mentored students interested in STEM careers, wanting them to have more support for their dreams than she did growing up. At NASA, she worked with summer interns at Goddard Space Flight Center. She was a youth mentor for the National Technical Association (NTA) and Women in Science and Engineering (WISE). She also spends time as a substitute teacher at DuVal High School, a science and technology public charter school in Maryland. When her students google her and find out she used to work at NASA, they ask her why she is there – her response: “I’m here to inspire students.”

Want to Know More?

Thomas, Dr. Valerie L. “Patent 4,229,761: Illusion Transmitter” (Oct. 21, 1980).

Green, James L. “Valerie L. Thomas Retires” (NSSDC News Sept. 1995).

Rocchio, Laura E.P. “A Face Behind Landstat Images: Meet Dr. Valerie L. Thomas” (NASA Feb. 28, 2019).

Staff. “Valerie Thomas Biography” (Biography.com Apr. 2, 2014 updated Mar. 6, 2020).

Staff. “Valerie Thomas: Illusion Transmitter” (Lemelson-MIT).

Boyd, Padi (host). “From Space to Farm” (NASA Podcast Nov. 2, 2020).