Amazing Artist

She taught herself how to draw and paint while attending an Indian day school operated by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and defied both federal forced assimilation policy and traditional Pueblo culture when she depicted scenes of everyday live and ceremonial rituals in her watercolor paintings. Travel to the American Southwest in 1931 and meet Tonita Peña …

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

Tonita “Quah Ah” Peña read the letter from New York City a second time. It was December, 1931, and her watercolor, Spring Dances, won the “Best in Show” award at the 1931 Exposition of Indian Tribal Arts.

The Exhibition, held at Grand Central Art Galleries in New York City, was the first time Tonita’s work was exhibited outside the Southwest. And it was a breakthrough moment for Native American art. The Exhibition featured 650 works of art from 21 different tribes — including pottery, weaving, and painting.

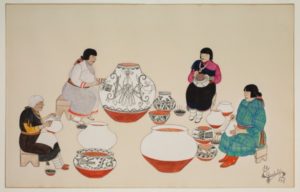

“Basket Dancers” by Tonita Peña, Detroit Institute of Art

The Exhibition ran for 3 months in New York, then toured the country for 15 months, until 1933. Further, some of the works traveled to Venice and Paris for display. It provided the general public a glimpse into the details of Native life. And it re-defined creative works by Native Americans as “fine art” that had intrinsic beauty and value, rather than “anthropology” objects.

Tonita’s watercolors focused on the role of women in Pueblo life — both everyday events and ceremonial dances. She celebrated women’s roles in Pueblo culture and placed them as central figures in her watercolors. In addition, many of her watercolors highlighted women’s participation in traditional ceremonial dances and other sacred rituals.

Even though she celebrated the roles of women in Pueblo culture through her art, Tonita refused to be limited by those same expectations. There were defined roles in the the creation of Native art — Pueblo women made pottery and Pueblo men painted pottery. Further, only Pueblo men could portray living people in their art. Traditionally, women didn’t paint. At all. Ever. However, Tonita broke through that boundary and chose two-dimensional easel painting as her artistic medium.

Tonita’s art was also an act of resistance against the federal government’s cultural assimilation policy. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, the federal government tried to force Native Americans to assimilate into white American culture and leave their traditions behind. For example, the Bureau of Indian Affairs banned traditional clothing, language, art, and dancing among Native Americans. In addition, children were forced to attend Indian boarding schools (sometimes miles from home).

Tonita’s art was also an act of resistance against the federal government’s cultural assimilation policy. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, the federal government tried to force Native Americans to assimilate into white American culture and leave their traditions behind. For example, the Bureau of Indian Affairs banned traditional clothing, language, art, and dancing among Native Americans. In addition, children were forced to attend Indian boarding schools (sometimes miles from home).

Since Tonita felt the traditional Pueblo way of life was under attack, she decided to document the Pueblo traditions through her art. She re-created ceremonial dances in her watercolors to preserve them for future generations. She made multiple paintings of each ceremonial dance, with each one showing a different moment — together, her paintings were a narrative of the entire dance. Tonita was determined to defend and celebrate her cultural heritage through her art. And she became an influential Native artist along the way.

The Power of the Wand

Tonita was the first Pueblo woman to paint with watercolors on paper. She went on to teach art to the next generation of Native American artists at both the Santa Fe Indian School and the Alburquerque Indian School. Tonita also inspired her son, Joe Herrera, who became a professional artist as well. Today, Native nations continue to seek ways to preserve their culture. For example, the yəhaw̓ Indigenous Creatives Collective is based in Seattle and supports Native teen artists through workshops, artist residencies, and an Indigenous Teen Art Show.

Her Yellow Brick Road

By the time Tonita was 25 years old, she was a successful painter. She sold her art to tourists from the plaza in Santa Fe, under the portal to the Palace of Governors. Her work was displayed in art galleries in both Santa Fe and Alburquerque and featured in museum exhibitions. Some of her work even decorated the walls of Santa Fe’s largest hotel, La Fonda.

Tonita pursued her art career despite criticism from other tribal members — some were angry that she defied traditional gender norms; some were offended that her art portrayed sacred rituals; and others were upset that her art was intended for sale to white patrons.

Tonita’s third husband, Epitacio Arquero, was completely supportive of her art career. And his support helped to quell objections to her art, since he was part of the tribal leadership for many years. Her painting was a family affair — the older children would care for the younger ones so Tonita could have some time to paint. In addition, she enlisted her children to swat flies away from the paint while she was working and help her deliver art to various galleries.

Tonita’s third husband, Epitacio Arquero, was completely supportive of her art career. And his support helped to quell objections to her art, since he was part of the tribal leadership for many years. Her painting was a family affair — the older children would care for the younger ones so Tonita could have some time to paint. In addition, she enlisted her children to swat flies away from the paint while she was working and help her deliver art to various galleries.

Tonita established herself among the first generation of Pueblo painters. In fact, she was the only woman in the “San Ildefonso Self-Taught Group” — they experimented with adapting traditional Native art into a form that would be appreciated by white patrons and were the first to commercialize Native art. The artists had no academic training, as defined by the western art world. But they were talented. And they merged classic Pueblo art with conventional painting techniques.

There was intense interest in Native American art in America during the 1920 and 1930s. People were searching for a unique American identity and were fascinated by the “original” Americans. They sought a reprieve from the turmoil in Europe during and after World War I. As a result, there was an increase in tourism to Santa Fe and other parts of the Southwest. Tourists wanted souvenirs of the travels. Tonita was happy to sell her paintings to them and share her beloved Pueblo culture along the way.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Tonita began painting and drawing at an early age, while attending the San Ildefonso Day School (a government-run school for Native children). In fact, she was considered a child prodigy at 7 years old. Her teacher, Esther Hoyt, encouraged her to paint and draw whatever she wanted as a way to express her feelings (which was in violation of the forced assimilation policy). She provided Tonita with crayons at first, then purchased some watercolors for her when it was clear that she had talent.

“The Vessels are Decorated” by Tonita Peña, Detroit Institute of Arts

While attending San Ildefonso day school, Tonita’s talent caught the eye of Dr. Edgar Hewett. He provided Tonita with art supplies for many years and encouraged her to paint anything and everything. She focused on the everyday tasks that took place around her, such as making pottery, grinding corn, and harvesting wheat. Hewett continued to support Tonita for many years, providing her with high quality watercolors and paper and purchasing much of her work for the Museum of New Mexico in Santa Fe.

When she was 12 years old, Tonita’s childhood changed drastically. Her mother and younger sister died of influenza and her father was unable to care for her. So Tonita moved to the Cochiti Pueblo to live with her aunt and uncle, who were both artists. Her aunt, Martina Vigil, was a talented potter. And her uncle, Florentino, was an accomplished painter who decorated all of Martina’s pottery.

It was a tough move — Tonita had to learn a new language, customs, songs, and dances. Even though it was only 50 miles away, it felt like another world. She was homesick and turned to her paints for solace. She also helped her aunt make pottery, who was losing her eyesight due to glaucoma.

It was a tough move — Tonita had to learn a new language, customs, songs, and dances. Even though it was only 50 miles away, it felt like another world. She was homesick and turned to her paints for solace. She also helped her aunt make pottery, who was losing her eyesight due to glaucoma.

Tonita continued her education at St. Catherine’s Indian School in Santa Fe. Three years later, however, the tribal elders arranged a marriage for her. So Tonita left school and married Juan Chavez when she was 15 years old. They had two children with 4 years, so Tonita had very little time for painting. After Juan died, it was arranged for Tonita to marry Felipe Herrera. During their marriage, she was able to complete her education at St. Catherine’s and return to her first love, painting.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- Tonita Peña was born on May 10, 1893. Her Native name, Quah Ah, means “White Coral Beads.” Her mother and sister passed away when she was 12 years old and her father was unable to care for her. So she moved in with her aunt and uncle.

- Tonita married 3 times. She married Juan Chavez in 1908 (it was an arranged marriage and she was only 15 years old). He died a few years later, and she married Felipe Herrera in 1913 (another arranged marriage). After he died, Tonita married Epitacio Arquero when she was 22 years old. She had 6 children in total, among her marriages.

- Tonita participated in the 1931 Exposition of Indian Tribal Arts in New York City and the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair. She also painted several murals in New Mexico.

- In 1932, the Whitney Museum bought a watercolor entitled “Basket Dance” for $225. It was the highest price paid for a Pueblo painting at the time — most sold for between $2-25.

- Tonita died on September 9, 1949 of cancer. After her death, her husband burned her personal effects and unfinished paintings — it was a Pueblo tradition.

- Tonita’s watercolors are part of the collections at: Cleveland Museum of Art, American Museum of Natural history, Heard Museum, Dartmouth College Collection, Peabody Museum, and many other museums.

- A crater on the planet of Venus is named in Tonita’s honor.

Want to Know More?

Gray, Samuel. Tonita Peña: Quah Ah, 1893-1949. Albuquerque: Avanyu Publishing, 1990.

Jantzer-White, Marilee. “Tonita Peña (Quah Ah), Pueblo Painnter: Asserting Identity Through Continuity and Change.” American Indian Quarterly. University of Nebraska Press (Summer, 1994), pp. 369-382. (https://www.jstor.org/stable/1184742).

Rushing III, W Jackson. Generations in Modern Pueblo Painting: The Art of Tonita Peña and Joe Herrera. Norman, OK; University of Oklahoma, 2018.

Sonneborn, Liz. A to Z of American Indian Women. New York: Facts On File, 2007.

The Exposition of Indian Tribal Arts, Inc. Introduction to American Indian Art. New York: College Art Association, 1931.