Awesome Athlete

She learned to swim in her backyard at a time when girls weren’t encouraged to be competitive athletes. At age 8, she asked her dad to let her try a swim meet and ended up setting records at her very first one. Seven years later she became an Olympic champion. Travel back in time to the last Tokyo Olympics in 1964 and meet Sharon Stouder…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

Sharon Stouder sometimes had to pinch herself to make sure she wasn’t dreaming – she really was competing for the United States at the Tokyo 1964 Olympics. Just.a few weeks ago, Sharon had been a 15 year old honor student at Glendora High School in California. But today, she was getting ready to dive into the pool for final race of the Tokyo Games: the 4×100 Medley Relay. Sharon was swimming butterfly in the third leg of the relay.

It had been an amazing week for Sharon. She was part of the first Olympics ever held in Asia. It was the first swim meet to use electronic touchpads, which meant that close races could be decided without any human error. And while only 13% of the Olympic competitors were women (678 of 5,151), the competition was fierce.

It had been an amazing week for Sharon. She was part of the first Olympics ever held in Asia. It was the first swim meet to use electronic touchpads, which meant that close races could be decided without any human error. And while only 13% of the Olympic competitors were women (678 of 5,151), the competition was fierce.

Sharon’s week had been busy. She was entered in 4 of the 8 swimming events open to woman at the Olympics: 2 individual events (100 freestyle and 100 butterfly) and two relay events. While she believed she had a chance to medal if she swam well, she was not favored to win either of her individual events. She was swimming against two world record holders: Australian Dawn Fraser who had been dominating the 100 freestyle for years, and 100 butterfly champion Ada Kok of the Netherlands.

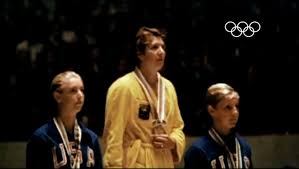

Sharon, Dawn Fraser, and Kathy Ellis on the medal podium after the 100 free (AP)

Sharon’s first race was the 100 freestyle. Preliminaries and semifinals on October 12 knocked the field down from 44 swimmers to 8. Sharon was the second fastest qualifier for the October 14 finals, which put her in a lane right next to Dawn Fraser. Sharon looked up to Dawn, who was the only woman in the world who had ever swam this event in under a minute. Sharon knew that if she could keep up with her, she might also achieve that milestone.

As they dove in the pool, Dawn went out to a small lead for the first 50 meters. At the turn, disaster struck when Sharon misjudged the turn and didn’t get a push off the wall. Sharon was now a body length behind Dawn. Sharon was mad at herself – she had missed the turn because she was paying too much attention to Dawn. She refocused on her own race and put everything she had into the last 50 meters. Sharon caught up to Dawn with 25 meters left in the rae and the two swimmers fought to the end, with Dawn just out-touching Sharon for the Gold by 4/10ths of a second. Sharon’s time was 59.9, making her the second woman, and first American woman, to break a minute in the 100 free.

Sharon and Ada Kok.

Sharon was tired. The 100 butterfly preliminaries and semifinals had been earlier in the day, beginning her quest to catch another superstar had been i. Ada Kok was such an overwhelming favorite that the Prince of the Netherlands flew to Tokyo to watch the race and be the one to present Ada with the gold medal.

The preliminaries had been fast and furious – with two people setting Olympic records before Sharon even got in the pool. But when she did, she set her own Olympic record with a 1:07.0. Sharon then broke her new Olympic record in the semifinals with a 1:05.6 setting up the finals showdown with Ada two days later.

In the meantime, Sharon had another race to swim – the October 15 4×100 free relay. Sharon was the lead-off swimmer and jumped out to such a huge lead that the race was essentially over before her three teammates even swam their legs. Their team smashed the world record by 4 seconds with a 4:03.8, finishing 3.5 seconds ahead of the silver medalists.

The following day, at the October 16 butterfly final, Sharon was no longer an unknown to anyone who had seen her previous swims. But she didn’t need the element of surprise – Sharon got off to a fast start and led the whole way, finishing almost a second ahead of Ada with a 1:04.7. The gold medal and new world record were hers. Her finals time was 2.5 seconds faster than her preliminaries time – a major accomplishment in only 100 meters.

The following day, at the October 16 butterfly final, Sharon was no longer an unknown to anyone who had seen her previous swims. But she didn’t need the element of surprise – Sharon got off to a fast start and led the whole way, finishing almost a second ahead of Ada with a 1:04.7. The gold medal and new world record were hers. Her finals time was 2.5 seconds faster than her preliminaries time – a major accomplishment in only 100 meters.

And now, 6 days after her first rave, Sharon was climbing on the block for her last event of the Olympics: swimming butterfly in the 4×100 medley relay. When Sharon dove in for her relay leg, her team was in first by inches. When she touched the wall at the end of her swim they were 2.5 meters ahead. By relay’s end, the United States had another gold medal and relay world record with a time of 4:33.9.

Standing on the podium with her third gold medal around her neck and the National Anthem playing, Sharon had no idea how famous this moment would make her, or that when she returned home from Tokyo there would be 3000 people waiting for her at Los Angeles International Airport. She heard crowds cheering and band music playing as she walked to customs and had to be told that everyone was there to see her!

The Power of the Wand

Sharon became a swimming superstar in the United States and inspired girls to try the sport. There were more than twice as many Olympic opportunities for women just 4 years later – the 1968 Olympics had 14 swimming events for women. When the Olympics returned to Tokyo in Summer 2021, there were 17 traditional events for women, as well as an open water competition and a mixed gender relay.

Teenage swimmers like Lydia Jacoby made Tokyo 2020 their own just like Sharon did in 1964. Lydia, a 17 year old high school student from Seward, Alaska, made her mark on swimming history with a surprise win of her own in the 100 breaststroke. Her gold medal was a first in swimming for Alaska, and she added to it with a silver medal in the 4×100 medley relay.

Her Yellow Brick Road

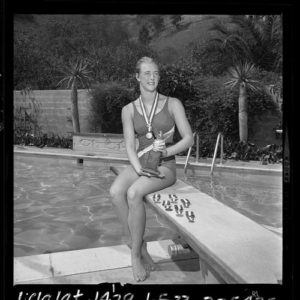

Sharon with many of her pre-Olympic medals and awards.

Once Sharon started swimming competitively when she was 8, her favorite strokes were freestyle and butterfly. She worked on achieving qualifying times for national meets. She started setting age group records – first in 8 & under, then 10 & under. When she was 12, she won 20 national age-group events. She also was at the top of all 6 National Junior Olympics ratings in her age group. She made such a big impression that American Swimmer Magazine named her the 1961 Girl Age-Group Swimmer of the Year.

Sharon and her parents realized if she was going to move to the next level, she needed a bigger place to practice than her backyard pool. They began looking for an Olympic size pool where she could train. The best option was a pool 50 miles away where she could swim with the City of Commerce swim team. Her parents drove her there twice a day for practice. They had to leave the house at 5:30am so she could practice before school. And then after school they made the trek again. They drove 200 miles a day for Sharon’s dream.

When Sharon was 13, she made her first appearance at the Senior Outdoor Nationals. She traveled to Chicago for the meet and took second place in the overall standings. She traveled even farther away from home the following year when she competed at the Pan American Games in San Paulo, Brazil. Sharon swam in both womens relays – freestyle and medley. And both relays won gold.

Sharon turned 15 in 1964 and had a full program of swimming. In April,she swam at the AAU Indoor Championships. In August, Sharon traveled to the AAU Outdoor Championships. She came away with first place finishes in the 100 meter freestyle, 100 meter butterfly and 200 meter butterfly. She beat her own world record in the 200.

The Olympic trials were held at the Astoria Pool in Queens, New York from August 29-September 3. The Olympics hosted fewer events for women than in the AAU meets, so Sharon’s chances to make the team were in just two individual events – the 100 fly and 100 free – and the two relays. Sharon swam well, made the team, and returned home to start planning her trip to Tokyo.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Sharon grew up in California, where the weather made it possible to swim outside most of the year. Her father, Galen, swam collegiately at UC Berkeley. He became the neighborhood swim instructor, teaching Stouder and several other local children. One of his students joined Stouder on the 1964 Olympic team, while another went on to win an NCAA swimming championship.

Sharon was only 3 years old when she learned to swim in her backyard pool. Her dad was her teacher. He had been a college swimmer at University of California, Berkeley and now offered swim lessons to neighborhood kids. Sharon loved swimming, and spent most of her free time in the water. At first, it was just for fun – especially since girls weren’t encouraged to pursue competitive sports. But when Sharon was 8, she asked her parents if she could enter a swim meet. Her dad said yes and Sharon found herself competing against 250 other kids her age. Although she had never formally trained, she won two events and set age-group record times in both. She hadn’t known how fast she really was until then. Now she knew. She was fast.

Sharon was only 3 years old when she learned to swim in her backyard pool. Her dad was her teacher. He had been a college swimmer at University of California, Berkeley and now offered swim lessons to neighborhood kids. Sharon loved swimming, and spent most of her free time in the water. At first, it was just for fun – especially since girls weren’t encouraged to pursue competitive sports. But when Sharon was 8, she asked her parents if she could enter a swim meet. Her dad said yes and Sharon found herself competing against 250 other kids her age. Although she had never formally trained, she won two events and set age-group record times in both. She hadn’t known how fast she really was until then. Now she knew. She was fast.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- Sharon was very famous after her Olympic success. Sports Illustrated Magazine named her “World Woman Swimmer of the Year.” The Los Angeles Times chose her as 1965 Woman of the Year. The Rose Parade had a float dedicated to her called “Miss Ideal Teen.”

- Sharon was invited to the White House to meet President Lyndon B. Johnson after the Olympics, She was invited with a mailed invitation, and when she took the envelope out of her mailbox, she initially thought it was from the White House Department Store in San Francisco.

- Sharon struggled with her newfound fame after she returned home. For the first year after the Olympics, it was hard to commit to a regular training schedule because she was serving as a Sports Ambassador for the U.S. State Department and also was in demand for various award shows. She was traveling around the country and missed being at school with her friends. She soon grew disillusioned with the attention and uncomfortable with the insincerity of being famous. She even turned down sponsorship offers from major brands like Wheaties and Coke.

- When Sharon finally had time to get back into the pool, Sharon seriously injured her back during training. She worked hard to heal and swim in the 1966 National Championship but sprained her ankle shortly before the competition. She had to swim one legged.

- Sharon attended the 1968 Olympic Trials with measured hopes given her struggles since the 1964 Tokyo Games. At the trials, the top three finishers in each event made the team. Sharon and another swimmer tied for third place with the time of 1:05.02, but the official awarded third place to Sharon’s competitor. Controversy ensured, but the call stood and Sharon did not make the Olympic team.

- Sharon attended Stanford University and swam for their women’s team. Stanford inducted Sharon into its Hall of Fame in 1997.

- Sharon coached swimming in Santa Barbara while attending graduate school there.

- Sharon married Ken Clark and had two children, Kerry and James.

- Sharon was inducted into the International Swimming Hall of Fame in 1972.

- Sharon started a women’s store she named Dash Leather and Apparel in 1979. She operated it until she retired in 2004.

- Sharon was chosen by Stanford to to light the Olympic torch in Stanford Stadium, which hosted soccer matches during the 1984 Olympics.

- Sharon died on June 23, 2003. She was 64.

Want to Know More?

Staff. “Sharon Stouder (USA) 1972 Honor Swimmer” (International Swimming Hall of Fame).

Staff. “Sharon Marie Stouder” (Olympics.com).

Keith, Braden. “Queen of 1964 Olympics Sharon Stouder Passes Away at 64” (Swim Swam July 10, 2013).

Martin, Sean. “Sharon Stouder Won Four Olympic Medals as a 15-Year-Old Swimmer in 1964” (San Luis Obispo Tribune Dec. 5, 2013).