Audacious Adventurer

She was only a child when she was taken away from the only family she had every known to live with strangers. Her curiosity caused her to cross paths with Meriwether Lewis and William Clark. Her bravery, resourcefulness, communication and survival skills were essential to their successful exploration of the American West. And she did it all with her infant son strapped to her back! Travel with us to 1804 Idaho Territory and meet Sacagawea…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

Sacagawea turned her head to smile at the infant strapped to her back. Her son, nicknamed Pomp, was happy there, having grown accustomed to the motion and sights as his mom walked the riverbank or rode in a boat on the Missouri River. It had been more than four months since April 7, 1804, the day they left Hidatsa tribal land in North Dakota to head west with the Lewis & Clark expedition. Sacagawea, a Shoshone Indian who had been kidnapped by the Hidatsa years before, and her husband, Toussaint Charbonneau, a French-Canadian trader, were on the trip to serve as translators.

“Lewis & Clark on Lower Columbia” (Charles Harrison)

There were 32 people and one dog on the journey, traveling in 6 canoes and 2 sailboats. Sacagawea knew she had proved her value quickly. She was skilled at identifying and finding edible plants, like currants, gooseberries, and roots. They also had gotten practice navigating the language barrier, which would be necessary when they reached the Shoshone tribe to bargain for horses to cross the Rockies. Sacagawea spoke Hidatsa to her husband, he spoke French to one of the members of the team, and that man did the final English translation for Lewis & Clark.

Sacagawea had already saved the expedition once. Back in May, she was riding on the sailboat as her husband was at the helm. Most of the expedition’s most valuable equipment and supplies were on the boat. When a squall of wind hit, Charbonneau panicked and let go of the rudder. The boat tipped to one side and dumped many of the supplies into the water. He froze, but Sacagawea quickly retrieved everything before it sunk. Had she not done so, they would have had to turn around. Lewis & Clark were so grateful they named one of the nearby creeks the Sacagawea River.

Sacagawea was proud of how quickly the others had come to rely on her. In addition to her foraging skills, she was a keen observer and was good at tracking prey. She also knew which plants to use to treat the illness, snake bites and insect stings the team suffered as the terrain got more difficult at higher altitudes. When she had fallen ill for two weeks in June, Clark was able to use her bark tea and mineral water concoctions to nurse her to health.

She also had helped them navigate a difficult portage around the 400 foot tall Great Falls. They fought cactus thorns, dodged grizzly bears, and barely escaped a flash flood by scrambling up a ravine to escape 15 feet of rushing water. When they finally arrived at the other side of the Falls on July 1, Sacagawea realized she had been there before – it was where she.had been abducted 5 years earlier.

The group had split up to look for the Shoshone tribe. Sacagawea went with Clark by canoe and Lewis took some men by land. Sacagawea turned her head back from Pomp and walked with Clark towards Lewis, who was standing with two Shoshone women, a girl, and 60 Shoshone warriors who had come to see what the white men wanted. Sacagawea couldn’t believe her eyes – one of the women was her childhood best friend who had also been kidnapped but escaped.

When they arrived at the Shoshone village, Sacagawea was presented to the Chief. She burst into tears because the Chief was her older brother! She tried to control her tears while she helped with the translations. An agreement was reached: the Shoshone provided horses and guides in return for battle axes, knives, and clothing.

Sacagawea then enjoyed several days with her surviving family – her two brothers and her sister’s son. There was a tense moment when she overheard the Chief say he planned to break the deal and keep the horses. Sacagawea felt divided loyalty, but decided to tell her husband what she had heard – they had come too far for the journey to end now. They confronted her brother, who then decided it would be shameful to break his word. The expedition said goodbye to the Shoshone and set off for the mountains.

Sacagawea reunited with the Shoshone (“Lewis & Clark Expedition” – Charles Harrison)

The horses made it easier but the conditions in the mountains were terrible, with snow, cold, and little food. It took more than a month to complete the crossing, and when they did, they stopped to rest, make new canoes, and arrangements with the Nez Peirce Indians to care for their horses while they finished the journey.

They paddled their way towards the Pacific Ocean. Sacagwea made their safe passage through tribal lands possible, as white men traveling with an Indian woman and a baby were not seen as a war threat. As the days went on, the rains came fast and furious. The canoes rotted and there were mold and fleas everywhere. But they persevered, and finally, on November 7, 1805, they arrived at the ocean. Sacagawea looked over her shoulder at Pomp – and smiled.

The Power of the Wand

Traversing 4000 miles over 14 months with an infant on your back is a remarkable feat. Sacagawea did that while also providing the essential survival and translation skills the Lewis & Clark expedition needed to be successful. The National Park Service created the Lewis & Clark National Historic Trail where you can retrace their steps.

Her Yellow Brick Road

Thomas Jefferson had wanted to sponsor an expedition to explore the American West since the 1790s.He craved information about its geography, natural resources, wildlife, and the Indians who lived there. His goal became a reality after he was elected President, oversaw the Louisiana Purchase of millions of acres of western land from France, and Congress approved funding to explore it.

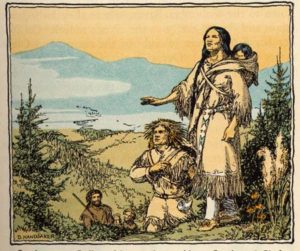

“Sacagawea An Indian Girl” (D. Handsaker)

He asked one of his personal aides, Meriwether Lewis, to head up the expedition. They decided to extend the journey past the Louisiana Purchase and travel as far as they could into the Pacific Northwest. Lewis asked his former Army Commander, William Clark, to join him in the planning and execution of this extraordinary journey. Clark was a brave man who could sketch and draw maps – a necessary skill for exploring unchartered territory. They invited a crew to join them for a training camp in St. Louis during the winter of 1803-04.

After months of intense planning and preparation, the expedition departed St. Louis on May 14, 1804. They had decided that navigating their way west via the nation’s rivers would be the most efficient and least risky way to cover large amounts of territory. They rowed the large canoes they had built upstream on the Missouri River.

They expected to met various Indian tribes along the way. President Jefferson had specifically instructed them that “in all your dealings with the Indians, treat them in the most friendly and conciliatory manner which their conduct will admit….” And as they made their way upriver, stopping to explore, document, and collect samples of what they discovered, Indian tribes came to observe. As they reached North Dakota territory, they met members of the Hidatsa tribe, who lived along the Knife River. The Hidatsa were familiar with white faces, as they frequently did business with French-Canadian traders.

“Sacagawea at the Big Water” (by John Cymer)

As winter grew near and the river started to freeze, Lewis & Clark looked for a place to spend the winter. They met a friendly tribe, the Mandans, who was willing to let them build cabins in near their village. They exchanged gifts of peace and the Mandans visited them often to watch them build their log cabins. The Hidatsas also wintered in the area, and were allies of the Mandans.

Sacagawea and her husband, a French Canadian trader named Charbonneau, were living with the Hidatsa. Sacagawea was curious about what the new arrivals were doing, so she and other of Charbonneau’s wives visited their camp and met Lewis & Clark for the first time. Sacagawea was 16 and pregnant with her first child.

Bronze of Sacagawea & Pomp near her birthplace in Idaho (NPS)

Lewis & Clark knew they would need horses for the expedition once the river ran into the Rocky Mountains. The easiest way to procure horses once they got to the mountains would be to trade with the Indian tribes who lived in the area. They discovered that the Shosone tribe would be their best bet. So they began looking for someone who spoke Shoshone and could translate for them.

They had met a French-Canadian trader, Charbonneau, who lived with the Hidatsa. Neither Lewis nor Clark liked him, but he was the only person they knew who spoke English and tribal languages. When they asked him, he told them that while he only spoke Hidatsa, one of his wives spoke Shoshone.

So Lewis & Clark hired Charbonneau to be their translator on the expedition so Sacagawea could accompany them to negotiate with the Shoshone. They offered him $500 and free lodging. Sacagawea and her husband moved into the log cabin with Lewis & Clark. It was here that she gave birth to her baby boy, Jean Baptiste. Lewis liked nicknames, and started calling the baby Pomp.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Sacagawea lived with her Shosone tribe in the western Rocky mountains of Eastern Idaho. The Shosone were a peaceful nomadic people who moved around with the seasons. She had a happy life with her parents and siblings. They carried their belongings, including the tipi they lived in, from place to place.

Sacagawea on a 1993 stamp

Sacagwea and her friends didn’t have any formal schooling. Instead, once they were old enough they helped the women with their work. Sacagawea learned to sew and helped make clothing and tipis for the tribe. She learned how to identify the berries and roots that were safe to eat, as well as which plants could be made into medicine. In their spare time, Sacagwea and her friends loved to organize running races and play games with balls they made out of hardened mud.

Every year, Sacagawea’s tribe spent the summer camping along the Snake River to fish. And then when fall arrived, they would trekked east across the mountains to the Three Forks area to hunt buffalo and gather food for the upcoming winter. Three Forks is in Montana between Butte and Bozeman, and is named after the three rivers that come together to form the Missouri River headwaters. It was an area with plentiful game for hunting and roots and berries for picking.

But when Sacagwea was 11, tragedy struck. While the women and children were berry picking, the men of her tribe were attacked by a group of Hidatsa warriors. The Hidatsa were a tribe from North Dakota territory who also had come to hunt the land.

Sacagawea Dollar Coin (2000)

The Hidatsa had a huge advantage – they came from the east, where trade with white settlers and traders was commonplace. This trade gave them access to guns. The Shoshone, from the west, did not. After fifteen Shoshone braves were killed by gunfire, the remaining realized they were no match for the Hidatsa’s strange and powerful weapon and fled. When Sacagawea heard the gun fire and the screams, she started to run too. A Hidatsa warrior spotted her and chased her into the middle of a river, where he caught her.

The Hidatsa warriors finished their hunt and then began the 600 mile trek back to their lands in North Dakota. Sacagawea and the other captives were forced to accompany them. One of Sacagawea’s friends managed to escape and run away. By the time the Hidatsa noticed she was gone, it was too late to find her. Sacagawea was sad to lose her companionship but hopeful that she would make her way back to the Shosone and that they would somehow see each other again. Sacagawea looked for her own opportunity to escape, but after losing one captive, the Hidatsa warriors made sure the rest of them were not given the opportunity.

When they arrived at the Hidatsa land in North Dakota, the warriors gave Sacagawea to one of the families to raise. She was in a strange place, with people she didn’t know and whose language she didn’t speak. She wondered whether her family had survived the raid. She missed them and her home immensely. But she adjusted to life with the Hidatsa, and then had to adjust again when the tribal Chief traded her to a French-Canadian interpreter named Toussaint Charbonneau to become one of his Indian wives.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- Sacagawea’s exact birthday is unknown. The best guess is that she was born in either 1788 or 1789.

- After reaching the ocean, the expedition built a camp on high ground near the Columbia River. They called it Fort Clastop, after the local Indian tribe, and spent the winter preparing for their journey home.

- On March 22, 1806, the expedition began the journey back east. As she did on the way there, Sacagawea was instrumental in identifying and foraging for edible plants to use for meals and medicine. By May, they reached the Nez Pence tribe to retrieve their horses for the trek across the mountains. On the other side, after returning the horses to the Shoshone, they built new canoes and floated back down the river towards the Hidatsa village where they first met Sacagawea.

- Lewis & Clark paid Charbonneau $500.33 for his and Sacagawea’s services on their 4000 mile, 14 month journey – the equivalent of two years pay.

- After Lewis & Clark said goodbye to Sacagawea and her family, they continued downriver to St. Louis. Their journey ended in late September, 1805, after 8000 miles and 28 months. There wasn’t much fanfare to greet them because most people had assumed they were dead.

- Clark kept meticulous journals detailing the expedition. His writings are the primary source for our understanding of the journey.

- Clark missed Sacagawea and her family. He had become particularly attached to her son John Baptiste (nicknamed Pomp), as he had helped care for him and was a witness to his first words and steps. Clark wrote Charbonneau, Sacagwea’s husband, and told him there would always be a home for them in St. Louis.

- Charbonneau and Sacagwea moved to St. Louis in 1809, when their son Pomp was 5. Clark had arranged for them to live on a farm not far from his property, Charbonneau grew restless and told Sacagawea they had to leave. Clark and his wife Julia offered to keep Pomp, promising to educate him and treat him as their own. While difficult, Sacagawea agreed, knowing it was a better life for Pomp than a life on the road with her.

- Sacagawea died in 1812, just after giving birth to her second child at a trading post in South Dakota. Charbonneau’s nomadic life wasn’t a good fit to raise a baby girl on his own, so he wrote Clark to ask if he wanted to adopt her too. Clark said yes, and baby Lisette joined her big brother as part of their family.

- Sacagawea’s son Pomp grew up to become a well-known guide and trader throughout the West. He eventually settled in a town in California and was elected its Mayor.

- Sacagawea lives on in the geography of the lands she traveled with Lewis & Clark. Mountains in Idaho, Wyoming, Montana, and Oregon named mountains after her. There also are lakes in Washington and North Dakota.

- The U.S. Mint issued a Sacgawea dollar coin in 2000.

Want to Know More?

Dippe, Brian. “The Imagery of Sacagawea” (Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum).

Clark, Ella E. & Edmonds, Margot. Sacagawea of the Lewis & Clark Expedition (Univ. of Cali. Press 1979).

Fraden, Judith Bloom. Who was Sacagawea (Penguin 2002).