Super Scientist

Her 1940s era high school offered students aptitude tests, but girls and boys were given separate tests suggesting different careers. When the girls’ test recommended she be a homemaker, she asked to take the boys’ test too – and it suggested research chemistry! After graduating as the only woman chemistry major at her college, she built a career at 3M and turned an accident into an invention that made homemaking easier for millions: Scotchgard™. Step back in time to 1953, watch what happens when synthetic rubber is accidentally spilled on a tennis shoe, and meet Patsy O’Connell Sherman…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

Patsy O’Connell Sherman couldn’t stop thinking about the accident that happened in the laboratory the previous week. She had a nagging feeling that the mishap contained a nugget of useful information. And she was officially fascinated. Patsy was convinced they had stumbled on a great opportunity. The building blocks of a new invention were in front of her. She just had to figure it out.

It was 1953 and Patsy was a research chemist at 3M. She and her colleague, Sam Sherman, were assigned to work on a military project. The new type of fuel used in airplanes tended to disintegrate the old rubber fuel lines. Their task was to develop a new kind of rubber compound that could withstand the harsh chemicals in the new jet fuel. Patsy’s role in the project was to work on flourochemicals — the compounds used in synthetic rubber material.

It was 1953 and Patsy was a research chemist at 3M. She and her colleague, Sam Sherman, were assigned to work on a military project. The new type of fuel used in airplanes tended to disintegrate the old rubber fuel lines. Their task was to develop a new kind of rubber compound that could withstand the harsh chemicals in the new jet fuel. Patsy’s role in the project was to work on flourochemicals — the compounds used in synthetic rubber material.

One afternoon, a lab technician was carrying a glass beaker filled with Patsy’s latest experimental compound. She accidentally dropped the glass beaker, which shattered and sprayed some of the compound on her white canvas tennis shoes. They scrubbed and scrubbed, but couldn’t wash the chemicals off the shoes. Everything just beaded off the fabric.

Before long, the tennis shoe had a white spot where the compounds had spilled — it stayed cleaner than the rest of the shoe. Nothing penetrated the spill. Not dirt. Not coffee. Not even ink. Patsy’s flourochemical compound protected the fabric and resisted stains and dirt. They all knew they had stumbled on an important discovery, one that could have tremendous value.

So, Patsy and Sam approached the spill with a new perspective. They stopped trying to fix the shoe. Instead, they started to learn from the shoe. How did the flourochemical compound resist stains and dirt? What made it attach to the fabric? Was it a fluke? Could they replicate it? Would it work on any fabric? Would it be invisible on any color? Could they coat large amounts of fabric with it? What is the best method for coating the fabric? How long does it take to dry? How long would the protection last? Patsy was determined to figure out the answers to all these questions, and many more.

After three years of hard work, Patsy and Sam perfected their fabric stain repellent and protector for wool material — it was called Scotchgard™. But they didn’t stop there. In the 1960s, they tweaked their formula to protect synthetic fabrics (nylon, polyester, etc). Then, they developed a variety of products for different applications such as clothes, shoes, household linens, upholstery, and carpet. Eventually, 3M produced almost 40 Scotchgard™ products. And the entire line was the most popular fabric protector in America for years.

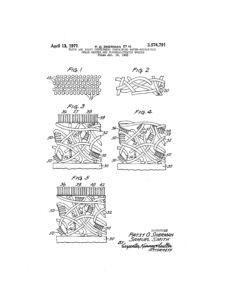

Patsy and Sam received US 3574791 on April 13, 1971, for the “invention of block and graft copolymers containing water-solvatable polar groups and fluoroaliphatic groups.” Before it was all said and done, they jointly held 13 patents in fluorochemical compounds. Clearly, they made a great team!

The Power of the Wand

Patsy was an inspiration to many women in the field of science. But she was also an inspiration to her family. Both of her daughters followed in her footsteps and became scientists. Sharilyn has a master’s degree in chemistry and worked at 3M for many years. Wendy is a biologist and owns a precision optics company.

Every year, 3M hosts a Young Scientist Lab Challenge, in connection with Discovery Education. Students in grades 5-8 from across America are invited to submit a video of their invention, which should provide a solution to an everyday problem. The finalists win a scholarship and mentorship — they are paired with scientists to test their inventions in the laboratory. In 2020, there were 10 finalists. And the winner was Anika Chebrolu, who “used in-silico methodology for drug discovery to find a molecule that can selectively bind to the Spike protein of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in an attempt to find a cure for the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Her Yellow Brick Road

In 1952, Patsy was hired at 3M as a “temporary employee.” And it wasn’t by choice. Back then, 3M didn’t offer women any permanent positions (with benefits and job security, etc). It was one of many American corporations that considered women to be a temporary workforce. Management assumed that women would only work for a short period of time before they got married and quit their job. Women were expected to stay home and raise future scientists, not be scientists themselves.

There were few women in corporate America in the 1950s. And even fewer women worked in laboratories. In fact, only 6% of chemists were women. On average, those women were paid only 60% of what their male colleagues earned.

There were few women in corporate America in the 1950s. And even fewer women worked in laboratories. In fact, only 6% of chemists were women. On average, those women were paid only 60% of what their male colleagues earned.

Patsy was a trailblazer. She was determined to have a career in science, regardless of the obstacles in her way. And she defied convention by continuing to work after getting married and having children.

During her first few years at 3M, Patsy ran into challenge after challenge. Frequently, she was the only woman in the room. As a result, she felt like an outsider at times. There were few restrooms for women on the 3M campus and some buildings were off limits to her. For example, women weren’t allowed inside the manufacturing buildings — it was considered to be too dangerous.

Diagram in Patent Application (US Patent Office)

3M’s policies made Patsy’s participation in the research and development of Scotchgard™ difficult as well. Patsy couldn’t be present during any of the fabric testing, since she wasn’t allowed inside the textile mills. So she had to sit outside and wait for someone to deliver the results to her. However, it wasn’t the same as observing the tests with her own eyes.

Patsy worked at 3M for her entire career. She was eventually hired as a permanent employee, with benefits. As the years went on, Patsy received some well-deserved promotions. She was promoted to laboratory manager in the 1970s. Then, she developed and ran 3M’s technical education department in the 1980s. Finally, she was promoted to Manager of Technical Development. In fact, Patsy was the first woman inducted into 3M’s prestigious Carlton Society in 1974, which honors the company’s top scientists.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Patsy grew up in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Her father was curious about science his entire life and set an example for Patsy. He encouraged her to follow her dreams, regardless of society’s expectations. Patsy grew up during World War II, when the traditional roles of men and women were upended. Millions of men were off at war. But work still had to be done at home. So women picked up the slack. They worked in factories. They ran family businesses. Many women loved the work and enjoyed the independence.

While in high school, Patsy completed an aptitude test. Back then, there were different aptitude tests for girls and boys. She initially took the girls aptitude test, which indicated that her best career choice would be “housewife.” Patsy refused to accept the results. She wanted a career. So, Patsy insisted that she be allowed to take the test normally given to boys. The test indicated that she should be either a dentist or scientist. She decided to study science.

While in high school, Patsy completed an aptitude test. Back then, there were different aptitude tests for girls and boys. She initially took the girls aptitude test, which indicated that her best career choice would be “housewife.” Patsy refused to accept the results. She wanted a career. So, Patsy insisted that she be allowed to take the test normally given to boys. The test indicated that she should be either a dentist or scientist. She decided to study science.

Patsy graduated in 1948 from Minneapolis North High School and was accepted into Gustavus Adolphus College in St. Peter, Minnesota. At the time, she was the only woman to major in chemistry at Gustavus. But that didn’t stop her. Patsy graduated in 1952 with a Bachelor of Science degree in chemistry and mathematics — the first woman in the college’s history to do so.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- Patsy O’Connell Sherman was born on September 15, 1930.

- Patsy attended Minneapolis North High School and Gustavus Adolphus College.

- Patsy married Hubert Sherman and they had two daughters, Sharilyn and Wendy.

- Patsy was hired at 3M in 1952 and worked there for her entire career, She was eventually promoted to a lab manager. Then, in the 1980s she developed and managed 3M’s new technical education development. She retired in 1992.

- Patsy’s invention of Scotchgard™ is considered one of the top 15 accidental inventions. She eventually held 13 patents with her colleague, Sam Sherman.

- In 2000, 3M reformulated the Scotchgard™ products to eliminate chemical compounds that were found by the EPA to harm the environment.

- Patsy spoke before school groups and others, encouraging young people to go into science as a career.

- Patsy was a member of the American Chemical Society for over 50 years. She retired in 1992.

- In October 2002, Patsy was one of 37 inventors who spoke at the United States Patent and Trademark Offices 200th birthday celebration. She spoke about the process of invention and said: “You can encourage and teach young people to observe, to ask questions when unexpected things happen. You can teach yourself not to ignore the unanticipated. Just think of all the great inventions that have come through serendipity, such as Alexander Fleming’s discovery of penicillin, and just noticing something no one conceived of before.”

- Patsy earned a number of awards over the course of her career:

- She was the first woman inducted into 3M’s prestigious Carlton Society in 1974, which honors the company’s top scientists.

- She was named to the Minnesota Inventors Hall of Fame in 1989.

- She was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2001.

- She became a Distinguished Alumni Citation Recipient for Scientific Research in 1975.

- The American Society for Engineering Education honored her with the Joseph M. Biedenbach Distinguished Service Award in 1991.

- Patsy died on February 11, 2008.

Want to Know More?

Proffitt, Pamela. Notable Women Scientists. Detroit: Gale Group, 1999.

“Patsy O. Sherman. Scotchgard™ Textile Protector.” National Inventors Hall of Fame (https://www.invent.org/inductees/patsy-o-sherman)

US Patent Application for “Block and graft copolymers containing water-solvatable polar groups and fluoroaliphatic groups.” US3574791 (https://patents.google.com/patent/US3574791)

“Innovative Lives: Patsy Sherman, Go Ahead—Put Your Feet on the Furniture!” March 3, 2005. Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation. (https://invention.si.edu/innovative-lives-patsy-sherman-go-ahead-put-your-feet-furniture)