Passionate Patriot

When she was a kid it was acceptable for high schools to ban girls from playing sports and taking classes in subjects like math and science. When she applied to college it was acceptable for universities to admit only a few women at a time and bar them from majors that were too “masculine.” When she was a Congresswoman, she wrote a law to change all of that. Join us in the halls of the 1971 Congress and meet Patsy Mink…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

Congresswoman Patsy Mink sat at a table during a House of Representative education committee hearing, listening intently to the testimony of woman after woman describing the discrimination they faced in education. The obstacles they encountered were widespread and relentless. They spoke of colleges requiring them to have higher test scores and grades then men, and then rejecting them because the school already had “too many women.”

Patsy was the first Asian American woman elected to the U.S. House of Representatives (public domain)

They recounted stories of being denied classes in engineering, medicine, or law because those professions were for men. They were often banned from “men only” public areas and were given earlier curfews and strict dress codes. Women professors shared how they were denied promotions because they were too aggressive. The women testified about their high school days, when they were discouraged from professional life and not allowed to play sports.

Patsy had lived these stories herself. It was 1971, she was 44 years old, and she had been fighting for her seat at the table since she was a girl in Hawaii. She loved playing basketball but her high school didn’t let girls play full court because it was too strenuous. She dreamed of becoming a doctor but was rejected by over 20 medical schools even though she was a top student. She was admitted to law school on a quota but after graduation no law firm would hire her.

When she first ran for political office, her own party had worked behind the scenes to get a man elected instead. Now she had a chance to level the playing field and make it easier for girls and women to pursue their dreams. The chair of the committee, Representative Edith Green, asked Patsy to draft a bill in response to the testimony they heard. Patsy said yes, and became the primary author of Title IX. Patsy’s Title IX draft bill was submitted to the House and Senate, which worked together for several months on the details. Title IX became law on June 23, 1972, and changed the world for girls and women with just one sentence: “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subject to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance”

When she first ran for political office, her own party had worked behind the scenes to get a man elected instead. Now she had a chance to level the playing field and make it easier for girls and women to pursue their dreams. The chair of the committee, Representative Edith Green, asked Patsy to draft a bill in response to the testimony they heard. Patsy said yes, and became the primary author of Title IX. Patsy’s Title IX draft bill was submitted to the House and Senate, which worked together for several months on the details. Title IX became law on June 23, 1972, and changed the world for girls and women with just one sentence: “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subject to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance”

The Power of the Wand

Patsy’s legacy is lived by today’s American girls every day. Since almost all public and private schools receive some kind of federal assistance, Title IX was incredibly powerful. It governed all activities and benefits offered by these schools, including admissions, financial aid, student services, and sports. Its impact has been immense. In 1970, before Title IX, 59% of women had a high school diploma, compared to 90% of women in 2017. Access to college programs show similar gains: only 8% of women had a college degree in 1970, compared to 35% of women in 2017. In 1972, only 7% of all high school athletes were girls, in 2016, 42% were girls. As of 2017, the numbers of girls playing high school sports increased from around 300,000 to over 3,300,000.

Patsy was in the position to write Title IX because she took a chance and ran for political office in a time where few women did. Check out the group IGNITE, an organization devoted to encouraging girls to become the next generation of political leaders. IGNITE sponsors programming and conferences for girls to learn about government, how to voice their opinions to policymakers, and how to run for office.

Her Yellow Brick Road

Patsy became politically active at in 1954 at age 27, having already fought several battles against discrimination. “I didn’t start off wanting to be in politics,” she reflected. “Not being able to get a job from anybody changed things.”

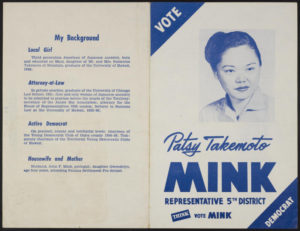

Patsy founded the Oahu Young Democrats and ran for a seat in the Hawaii Territory House. She lost, and spent the next two years planning for the next election. She spent hours walking through neighborhoods, knocking on doors and talking with potential voters, which was a revolutionary idea at the time. Patsy won and became the first Asian American woman elected to the Territory House. Two years later, she achieved the same with her election to Territory Senate.

Portrait of 1958 Hawaii Territorial Senate. Patsy was the only woman. (Patsy T. Mink Papers, Library of Congress)

In 1959, Hawaii became the 50th state and received one seat in the U.S. House of Representatives. Patsy put her hat in the ring, but the Hawaii Democratic party wanted a man in the seat and recruited a popular politician to run against her in the primary. Patsy lost, regrouped, and won a seat in the Hawaiian State Senate two years later.

Campaign flyer from Patsy’s 1956 campaign (Library of Congress)

When Hawaii received another seat in the House in 1964, Patsy tried again. Again, her party refused to endorse her, so she relied on small donations from individuals and a volunteer staff led by her husband. As she gained traction in the race, party leaders even encouraged other Democrats to support one of the Republican candidates to block her! Patsy’s candidacy was saved by Democratic President Lyndon Johnson’s popularity. Many voters chose Democrats all the way down the ballot, and Patsy became the first Asian-American woman elected to Congress.

When Patsy was first elected to the House, only 13 of the 435 representatives were women. They were not allowed to use the House dining room or gym. Their male colleagues often discounted their opinions, claiming that women were too emotional to make serious decisions. Those that were mothers were accused of neglecting their children. Patsy faced extra scrutiny, as media focused on her “exotic” looks and small stature.

Patsy and colleagues protesting the “men only” gym at the House of Representatives (Washington State University Libraries)

Patsy ignored the sexism and got to work. She requested and received a seat on the Committee on Education and Labor. She sponsored legislation supporting special education, bilingual education, the Head Start program and access to child care.

During her 3rd term, Patsy broke ground when she testified against a Supreme Court nominee who had previously ruled in favor of a company who refused to hire women with children to work on its assembly line. Patsy testified that his appointment would be “an affront to the women of America” because he “represented a vote against the right of women to be treated equally and fairly under the law.” Patsy’s testimony inspired others to dig deeper into the judge’s record, which also included membership at an all-white golf club and poorly reasoned legal opinions, and he was not confirmed.

Patsy’s passionate advocacy for girls and women led her to the education committee meeting where Title IX was born. But even after it passed, the fight wasn’t over. The mandate for equal opportunity in sports became controversial almost immediately. Many argued that boys shouldn’t be disadvantaged by having to share resources with girls. They claimed girls didn’t like sports and that it was too dangerous for them anyway.

Patsy’s passionate advocacy for girls and women led her to the education committee meeting where Title IX was born. But even after it passed, the fight wasn’t over. The mandate for equal opportunity in sports became controversial almost immediately. Many argued that boys shouldn’t be disadvantaged by having to share resources with girls. They claimed girls didn’t like sports and that it was too dangerous for them anyway.

Title IX opponents made their move to exclude sports from Title IX in 1975. Patsy worked tirelessly to persuade her House colleagues to preserve the law. Right before the vote, Patsy got a phone call that her daughter had been seriously hurt in a car accident and rushed to her side. Title IX opponents took advantage of her absence and the House voted to exclude sports by one vote: 212-211. After national news stories about the choice Patsy faced, the Speaker of the House scheduled a re-vote. This time, the House voted to keep the sports mandate by a 37 vote margin.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Patsy grew up on a sugar cane plantation in Maui, Hawaii. Her grandparents were Japanese immigrants. Patsy grew up witnessing the segregation of plantation life, where white bosses were treated much better than the Asian and Native Hawaiian labor force. Patsy’s dad, a civil engineer and land surveyor, was a pioneer himself. He was one of the first Japanese-Americans to graduate from the University of Hawaii.

The day after Patsy turned 14, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in Honolulu and the United States entered World War II. Japanese-Americans were viewed as potential enemies and were forced to move to internment camps on the mainland. There were no internment camps in Hawaii, likely because the plantations could not afford to lose their labor. Even so, Patsy’s dad was taken away for questioning in a scary time for the family.

Patsy’s high school (Friends of Old Maui High School)

Patsy’s childhood dream was to become a doctor and she worked hard towards that goal. She finished first in her class at Maui High, and was also the first girl elected class president.

She graduated from the University of Hawaii with degrees in zoology and chemistry and was president of the Pre-medical Students Club. Even so, no medical school would accept her, so she applied to law school instead. Luckily, the University of Chicago didn’t realize that Hawaiians were United States citizens and accepted Patsy as part of its foreign student quota.

While in Chicago, she met and married John Mink and they moved to Honolulu after her graduation. Patsy was initially barred from taking the bar exam because she was no longer considered a Hawaiian resident. Under state law, a woman’s residency was based on her husband. She challenged the law, and prevailed, but no law firm would hire her. They disapproved of her interracial marriage and her desire to be a working mother, plus no Japanese-American woman had every practiced law in Hawaii. Patsy started her own firm specializing in family and criminal law, and was paid by her first client with a fish!

Glinda’s Gallery

Visit Patsy’s digital scrapbook on Pinterest: https://www.pinterest.com/theglindafactor/patsy-mink/

Just the Facts

- Patsy was born in Paia, Maui, Hawaii Territory, on December 6, 1927.

- Patsy attended the University of Nebraska for a short time. She had to live in the international student dorm because the main dorms were limited to white students only.

- Patsy married John Mink in 1951. They had one daughter, Gwendolyn.

- Patsy was a key sponsor of the Women’s Educational Equity Act of 1974, which provided funding for schools to remove gender stereotypes from curriculum, like textbooks that encouraged boys to study medicine and engineering and girls to learn housekeeping skills.

- Patsy served in Congress for a total of 24 years in two different phases of her life: from 1965 to 1977 and from 1991 to 2002.

- She decided to run for Senate in 1976, lost in the primary, and moved back to Hawaii and local politics. Fourteen years later, at age 63, Patsy decided to run again for the House of Representatives, but her party endorsed a younger local businessman in the primary. Patsy won the primary, using “The Experience of a Lifetime” as her campaign slogan, and then won the general election easily. She never faced another primary challenge and won her next five general elections with over 60% of the vote.

- Patsy asked to rejoin the House Committee on Education and Labor, commenting that “I have been away from the Congress for about 14 years, and I am astonished to find that in the first month of my return here … we are still debating the question of what equality really means in this country.”

- Patsy predicted that Nancy Pelosi would one day become the first woman Speaker of the House.

- Patsy died on September 28, 2002 from pneumonia, five weeks before Election Day. Her name remained on the ballot and she won.

- Title IX was renamed the Patsy T. Mink Equal Opportunity in Education Act on October 29, 2002.

- In 2014, President Obama awarded her the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor, observing that “every girl in Little League, every woman playing college sports, and every parent, including Michelle and myself, who watches their daughter on a field or in the classroom, is forever grateful to the late Patsy Takemoto Mink. Patsy was a passionate advocate for opportunity and equality and realizing the full promise of the American Dream.”

Want to Know More?

Documentary: Patsy Mink: Ahead of the Majority. Directed by Kimberlee Bassford. Honolulu: Making Waves Films, 2008.

“Equal Access to Education: Forty Years of Title IX.” United States Department of Justice, 23 June 2012.

Wilson, Amy S., “45 Years of Title IX: The Status of Women In Intercollegiate Athletics.” National Collegiate Athletic Association (2017)

Patsy Takemoto Mink entry, History, Art & Archives, United States House of Representatives

Chan, Christina. “The Mother of Title IX: Patsy Mink.” The She Network, 24 Apr. 2012.

Hodges, Shay Chan. “Patsy Mink Lives On In Today’s Fight For Title IX.” We News, 26 Aug. 2015

Lee, Ellen. “Patsy Takemoto Mink’s Trailblazing Testimony Against A Supreme Court Nominee.” The Atlantic, 16 Sept. 2018.

Stringer, Kate. “No One Would Hire Her. So She Wrote Title IX and Changed History for Millions of Women. Meet Trailblazer Patsy Mink.” The 74, 1 Mar. 2018.