Amazing Artist

In less than three years, she went from being an award winning artist traveling and studying in Europe to a forced resident of an internment camp – in her own country – with a number assigned to her in place of her name. She used her drawing skills and her keen sense of observation to document daily life in a Japanese-American internment camp. Her illustrations and commentary became the first published account of what life was like for those forced from their homes when the United States entered World War II. Step back in time to 1942 as she becomes Citizen 13660 and meet Miné Okubo…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

In April 1942, Miné Okubo’s family received an official notice from the government that would change their lives forever. They were given 3 days to pack what they could carry and report to a “central relocation station” at the First Congregational Church in Berkeley. From there they were assigned to trains for transport to different internment camps around the country, where they were forced to live until further notice.

Miné’s drawing of arriving at the internment camp with her brother (Citizen 13660)..

Miné’s family were just a few of the more than 110,000 Japanese-Americans relocated to internment camps in the wake of the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor by Japan on December 7, 1941. Miné was a member of the Nisei generation – the children born in the United States to Japanese immigrants. Like many Nisei, she had never been to Japan and did not speak the language. Even so, the U.S. government decided these citizens – along with their first generation parents – were a potential threat. This paranoid fear that they would assist Japan in an attack against the mainland led to President Roosevelt issuing Executive Order 9066, which authorized the government to forcibly remove Japanese-Americans from their homes on the West Coast.

Miné, a working artist, and her brother Toku, a few weeks from his college graduation, were separated from the rest of their family. Their dad was sent to a high security camp in Montana because he was born in Japan and was an active member of a Japanese-American church. Four siblings were scattered among other camps, and one older brother was accidentally drafted by the military. Miné and Toku were assigned the “family number” 13660 and sent to the Tanforan detention camp in San Bruno, California.

Tanforan was an old racetrack and the facilities were terrible – Miné and Toku slept in a 20 foot by 9 foot horse stall. They didn’t have cots, but instead used cloth sacks stuffed with hay as mattresses. The smell of manure soon was a permanent stench on all of their belongings.

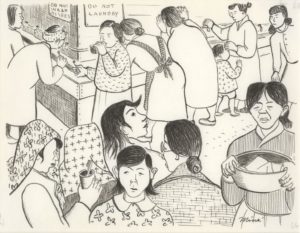

Miné’s depiction of the washroom at the camp. (Citizen 13660).

Miné had included art supplies in the limited baggage she was allowed. Cameras had been confiscated. The only photographs allowed were those the government chose to take. Miné’s life at Tanforan was so contrary to any American ideal of freedom that she worried the public wouldn’t believe it was happening. So she set out to draw what she was experiencing to illustrate “what happens to people when reduced to one status and condition.”

The internees had work duties during the day, so often Miné’s only time to draw was at night. She rarely slept more than a few hours because she wanted to capture the day’s events while they were fresh in her memory. Miné was allowed access to the mail and sent her friends at home some of her drawings to show them what her life was like. They were moved by the images and encouraged Miné to keep drawing to help people understand was happening inside the camps.

Miné found a group of artists among the internees, including a Berkeley professor and they brainstormed ideas to keep engaged and feel human. They started the Tanforan Art School, which offered classes to anyone – from children to senior citizens – living in the camp who wanted to learn. Interestingly, even though she was drawing what was happening, government officials identified Miné as someone with “special talents and abilities” who could benefit all of the internment camps.

Miné found a group of artists among the internees, including a Berkeley professor and they brainstormed ideas to keep engaged and feel human. They started the Tanforan Art School, which offered classes to anyone – from children to senior citizens – living in the camp who wanted to learn. Interestingly, even though she was drawing what was happening, government officials identified Miné as someone with “special talents and abilities” who could benefit all of the internment camps.

After six months, Miné and Toku were transferred to the Topaz camp in Utah. Although the facilities were better, the loss of identity was ever present, with the number 13660 still on all belongings. It even became their signature on documents. Everything was communal. They lived in barracks. They ate in a dining hall. The campgrounds were surrounded by barbed wire.

Like she did at Tanforan, Miné spent the nights drawing what had happened during the day, often nailing a quarantine sign on the barracks door to keep guards away. She found another group of interned artists and the Topaz Art School was born. There were many writers at Topaz who had started a newspaper for internees named the Topaz Times. Miné did illustrations for the paper and joined their efforts to create a literary magazine, which they named Trek. Miné served as Art Editor, doing the cover art and illustrating stories and poetry within.

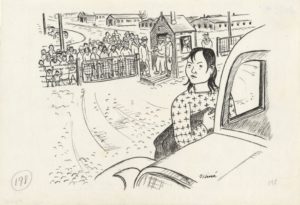

Miné’ captured the scene of when she was released from the internment camp to go to New York. (Citizen 13660).

Miné sent one of her sketches of a camp guard to the San Francisco Museum of Art for an exhibition. It won a prize, was reprinted in the San Francisco Chronicle, and the paper commissioned more sketches from Miné for its Sunday magazine. Her work for the Chronicle made its way to the editors of Fortune Magazine as they were working on a special issue about Japan. They thought Miné’s illustrations would be a perfect accompaniment and wrote to Miné offering to sponsor her release if she was interested in coming to work for them as a staff illustrator in New York City. She jumped at the chance for freedom and said yes. Her brother Toku already had been released to work at a wax-paper company in Chicago.

Camp administrators approved and Miné again was given 3 days notice to pack her belongings and leave. But this time she was going towards freedom instead of captivity and started her new life in New York in January 1944.

The Power of the Wand

Miné created nearly 2000 illustrations during her internment. She used whatever medium she could get her hands on – watercolor, charcoal, pen and ink, gouache. She captured the details of what she observed in camp every day. She published the first account of life inside an internment camp in 1946. Citizen 13660 included 206 of her pen and ink illustrations with her commentary alongside the images.

Miné created nearly 2000 illustrations during her internment. She used whatever medium she could get her hands on – watercolor, charcoal, pen and ink, gouache. She captured the details of what she observed in camp every day. She published the first account of life inside an internment camp in 1946. Citizen 13660 included 206 of her pen and ink illustrations with her commentary alongside the images.

Art has traditionally been a way for people to process difficult experiences, and there are many online resources for how to begin. Author Allie Brosh created a webcomic she called Hyperbole and a Half while procrastinating studying for a college physics exam. Allie used drawings and text to describe her experiences with ADHD and Depression. A few years later she collected her blog entries into a book titled Hyperbole and a Half: Unfortunate Situations, Flawed Coping Mechanisms, Mayhem, and Other Things That Happened. Her second book, published last year, is Solutions and Other Problems. Both are best sellers and also are widely praised by mental health professionals for their honest portrayal of living with mental illness.

Her Yellow Brick Road

Miné was a very successful art student at the University California, Berkeley. She was a painter at heart and experimented with many mediums while at school, eventually focusing on murals and fresco techniques. Her work was so accomplished that, in 1938, she won one of the highest honors the college awarded: the Bertha Taussig Traveling Art Fellowship. The fellowship provided Miné with a stipend for a two-year trip to Europe. Miné traveled around Western Europe, studying with various artists and experimenting with her own painting style. She started painting watercolors. Paris was one of her favorite stops – both for the beauty of the city and the chance to learn from famous painter and sculptor Fernand Léger.

While Miné soaked up everything Europe had to offer, she realized that the prospect of war loomed. She was painting in Switzerland when World War II began in September 1939. Although she still had 6 months left in her fellowship, she decided the safest course was to return home. But the borders were closed and she initially couldn’t find a way out of Switzerland. She persisted – her determination increased by a letter from her family with the news that her mom was very ill – and finally was able to get a visa to travel through France. She made it to the port in Bordeaux just in time to catch the last ship leaving for the United States.

While Miné soaked up everything Europe had to offer, she realized that the prospect of war loomed. She was painting in Switzerland when World War II began in September 1939. Although she still had 6 months left in her fellowship, she decided the safest course was to return home. But the borders were closed and she initially couldn’t find a way out of Switzerland. She persisted – her determination increased by a letter from her family with the news that her mom was very ill – and finally was able to get a visa to travel through France. She made it to the port in Bordeaux just in time to catch the last ship leaving for the United States.

Miné arrived home in California and her mom died shortly afterward. She took a job with the Federal Arts Project, which was hiring artists for the various buildings and parks being constructed by the Works Progress Administration. Miné spent most of her time painting murals and creating mosiacs at Ford Ord on Monterey Bay and the Oakland Serviceman’s Hospitality House. She also had the chance to work with famous artist Diego Rivera on his mural for the Golden Gate International Exposition on Treasure Island (in the middle of San Francisco Bay!).

Outside of work, Miné looked for opportunities to show the public her art from her European fellowship. She worked with the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, which agreed to host two exhibitions of her work. She was so excited to be building a career as a professional artist.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Miné’s parents first came to the United States in 1904 to attend the St. Louis Exposition of Arts and Crafts as representatives of Japan. Miné’s dad was a Japanese history and philosophy professor and her mom was a painter and calligrapher. They decided to stay and moved to California. In order to make ends meet, Miné’s dad got a job at a candy shop and then settled into a career as a gardener, while her mom stayed home to take care of their seven kids.

Miné showed interest in art from early childhood and her mom, who had been an honors graduate from the prestigious Tokyo Art Institute, encouraged her to pursue it. Miné was a quiet girl, but her shy demeanor hid the core of steel and confidence she built from learning how to stand up for herself in a household with lots of brothers.

Miné showed interest in art from early childhood and her mom, who had been an honors graduate from the prestigious Tokyo Art Institute, encouraged her to pursue it. Miné was a quiet girl, but her shy demeanor hid the core of steel and confidence she built from learning how to stand up for herself in a household with lots of brothers.

When Miné was 19, she enrolled in Riverside Junior College. She took some art classes and one of her professors was so impressed with her potential that he wrote a recommendation for her application to the University of California, Berkeley. She was accepted into the art program there and awarded a scholarship towards her tuition. She took on a series of odd jobs throughout college to make ends meet. She worked as a maid, a tutor, and even on a farm! Miné proudly earned her Bachelor’s degree in Art in 1935. She decided to stay on at Berkeley to do some graduate work, and a year later was awarded a Master’s degree in Art.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- Miné was born on June 12, 1912 in Riverside, California.

- Miné moved into a Greenwich Village apartment in New York City after she was released from the internment camp. Her apartment became a home away from home for many Japanese-Americans who left the West Coast after being released from the internment camps. She also built a wide circle of friends in the New York artist communities. Miné described herself as a “universal mother.”

- After her stint at Fortune, Miné spent several years working as a freelance commercial artist. Her illustrations were featured in many national magazines and newspapers, novels, and children’s books.

- In 1950, Miné decided to devote herself to painting full time. She returned to California for the first time since her internment to be a Lecturer in Art at the University of California, Berkeley. But she quickly realized New York City was now home and returned there in 1952.

- Miné spent the 1950s and 1960s experimenting with a different painting style that reflected her Japanese heritage and traditions. While she was personally fulfilled as an artist, she had difficulty finding galleries willing to exhibit her work because her paintings did not observe popular trends and she disliked the promotion side of the art business.

- In 1980, Congress created the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians in an effort to atone for the U.S. government’s treatment of Japanese-Americans during World War II. Miné testified before the Commission, describing her internment and how she used her drawings to show the outside world what life was like inside the camps.

- Citizen 13660 was published in 1946. After its single printing, it wasn’t released again until some small New York publishers reprinted it 20 years later for libraries. But in 1983, in the wake of Miné’s Congressional testimony, the University of Washington Press republished Citizen 13660. It then won the American Book Award in 1984.

- When Congress passed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 it marked the first formal acknowledgment and apology that the government acted illegally when it forced Japanese-Americans out of their homes and into internment camps. As part of this apology, Congress awarded each internee $20,000.

- Miné won the National Women’s Caucus of Art’s Lifetime Achievement Award in 1991.

- The Catherine Gallery in New York City hosted a 40 year retrospective exhibit of Miné’s work in 1985.

- Miné died on February 10, 2001 in New York City.

Want to Know More?

Surviving Internment: Illustrations by Miné Okubo (New York Historical Society Museum & Library).

La Duke, Betty. “On the Right Road, The Life of Miné Okubo” (Art Education Vol. 40, No. 3: 42-48 May 1987).

Spring, Kelly. “Miné Okubo” (National Women’s History Museum 2017).

Staff. “Citizen 13660” (Densho Encyclopedia).

Ueno, Rihoko. “Miné Okubo, Number 13660” (Smithsonian Magazine June 22, 2018).