Passionate Patriot

She was a free woman who posed as an enslaved servant so she could participate in a Civil War spy ring that was a critical element of the Union victory that ended slavery. She used her photographic memory and the assumption that she couldn’t read or write to gain access to documents detailing battle plans, troop movements, and other top secret military information. Peek into the Confederate White House in 1863 and meet Mary Richards Bowser…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

Mary Richards Bowser took a deep breath as she opened the servant’s door to the Confederate White House. It was her first day as an enslaved servant to Jefferson and Varina Davis. But it was all an act. Little did the Davis family know that Mary was no ordinary servant. In addition to being a free black woman, she was highly educated and had a photographic memory. And she was a spy for the Union.

Confederate White House in Richmond, where Mary was both a servant and spy for the Union (Library of Congress).

In what appeared to be Southern hospitality, Elizabeth Van Lew had visited Varina a few days earlier, welcoming her to Richmond and offering the services of Mary as a maid.

Mary was part of Elizabeth’s spy ring, the Richmond Underground. And she had known Elizabeth all her life. In fact, she was enslaved by the Van Lew family until Elizabeth granted her freedom.

Mary used Southern prejudices to her advantage — she knew the Davis family would assume that she couldn’t read, write, or comprehend what took place around her. And she was right. As a result, Mary gathered information for the Union right under the noses of the Confederate leaders.

Mary memorized all the documents she saw while cleaning Jefferson Davis’ office. And she remembered the conversations that she overhead, word for word. Then, Mary shared all the information with Elizabeth, who passed it on to the Union Army. It was a dangerous job — if Mary was caught, she would be hanged without a trial.

Mary memorized all the documents she saw while cleaning Jefferson Davis’ office. And she remembered the conversations that she overhead, word for word. Then, Mary shared all the information with Elizabeth, who passed it on to the Union Army. It was a dangerous job — if Mary was caught, she would be hanged without a trial.

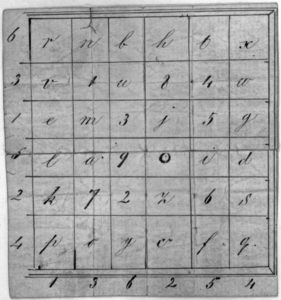

Elizabeth and Mary passed secrets to each other through a seamstress in town. Mary wrote a message using the cipher that Elizabeth gave her. She sewed the message into the waistband of Varina’s skirts and brought the skirts to the seamstress for cleaning or mending. The seamstress took the skirt apart, removed the messages, and passed them on to a member of the Richmond Underground.

Mary’s work was invaluable to the Union cause. She memorized the Confederate’s troop numbers, including the defectors, dead and wounded. She learned about Confederate Battle plans and secret troop movements. She found lists of ammunition storage and other supplies. She came across the blueprints for top secret military projects such as the CSS Virginia, a submarine-like “iron monster of the sea.” And she kept track of Union prisoners, including how may were held in the overcrowded prisons in Richmond (Libby Prison and Belle Island).

This photograph was originally thought to depict Mary. Later research showed it is likely another woman with a similar name.

The Union seemed to know every decision that was made by the Confederate leaders. So Jefferson Davis eventually suspected that he had a spy in the midst — and it drove him crazy. At first, Jefferson Davis thought a spy was in the War Department. But then, he turned his suspicions towards their household. Around the same time, Mary began to worry that she was being watched. So she decided it was time to get out.

Mary snuck out of the Confederate White House and made her way to the Van Lew mansion. And Elizabeth sprang into action — she had to protect her most valuable spy. Legend says that Mary hid under a wagon-load of manure and escaped to Philadelphia.

The Power of the Wand

Mary was a key player in Elizabeth’s spy ring. She pretended to be an enslaved woman, in the hopes that her work would end slavery. And it did. Elizabeth’s spy ring, the Richmond Underground, helped the Union win the Civil War. In fact, after the war ended General Grant sent Elizabeth a note of thanks, which said “You have sent me the most valuable information received from Richmond during the war.”

Since the Civil War ended, many Americans have worked to improve race relations. And African American young adults have been on the front lines for years — the Greensboro Four staged nonviolent sit-ins to protest segregation; the Freedom Riders traveled through the South to protest segregation in transportation; and thousands of students marched in the Birmingham Children’s Crusade to advocate for integrated schools. Nupol Kiazolu is continuing the legacy by advocating for an end to racism in America. She participated in her first protest when she was 13 years old, launched a voter registrar campaign, and is president of Black Lives Matter of Greater New York. And she has dreams of becoming President of the United States of America in 2036.

Her Yellow Brick Road

Mary and Elizabeth had a very complicated relationship — it was part friendship but mostly obligation. Mary was a former slave and Elizabeth was her former master. Elizabeth recognized Mary’s intelligence and paid for her education. Whatever the reasons, their relationship fostered one of the most unusual espionage partnerships in American history.

Elizabeth Van Lew’s cipher, which she and Mary used to secretly communicate (New York Public Library)

Elizabeth was the Union’s most valuable spy in the Confederal capital. She ran the Richmond Underground for about 15 months, until General Ulysses Grant captured Richmond in April of 1865. Mary and a number of other African Americans were pivotal to the Richmond Underground — they used secret signals, peach pit carvings, and copper tokens to identify each other. They also used a cipher and invisible ink to share information.

Elizabeth exploited the Southern views about women and African Americans. She took advantage of her station as a member of Richmond’s high society and presented herself as someone above reproach. Mary and her other servants were the key to Elizabeth’s spy network because no one paid any attention to them. They could talk freely to other slaves in town, spreading information and gathering intelligence. And they communicated through messages hidden inside eggs, produce, shoes, buttons, hats, and serving plates.

The Richmond Underground was also used to help Union soldiers escape to the North. Elizabeth established five safe houses between Richmond and the Union line, including her mansion and family farm. Mary used these safe houses when she escaped Richmond after leaving the Confederate White House.

The Richmond Underground was also used to help Union soldiers escape to the North. Elizabeth established five safe houses between Richmond and the Union line, including her mansion and family farm. Mary used these safe houses when she escaped Richmond after leaving the Confederate White House.

People in Richmond suspected Elizabeth of helping the Union. As a result, she was constantly in danger — neighbors spied on her; Confederate soldiers tried to entrap her; and her home was randomly searched (twice, she was hiding Union soldiers at the time). And the danger was even higher for Mary and other other African Americans in the Richmond Underground. Luckily, Elizabeth and Mary were vigilant and never caught.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Mary was born into slavery and grew up in the Van Lew household. But it didn’t take long for the family to recognize Mary’s extraordinary intelligence. As a result, Mary was treated differently than most slaves.

When she was five years old, Mary was baptized at St. John’s Church, where the Van Lew family were members of the congregation. This was highly unusual at the time and an honor given to no other enslaved people owned by the Van Lews.

Elizabeth Van Lew

Elizabeth begged her mother to grant Mary her freedom and send her to North to receive an education. It’s thought that Elizabeth enrolled Mary in a Quaker school located in either Princeton, New Jersey or Philadelphia. And she paid for everything — school, boarding, food, books and supplies.

After receiving an education, the Van Lews sent Mary to Liberia to be a missionary with the American Colonization Society. She spent five years there, but wasn’t happy. So the Van Lews paid for her passage on a ship back to America. She landed in Baltimore and made her way to Richmond.

When she arrived, Mary was promptly arrested for traveling without identification papers. At the time, it was illegal for an educated, free black person to live in Virginia. So Elizabeth paid the fine and claimed that Mary was her slave. After that, Mary kept her free status a secret and worked in Elizabeth’s household.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- It is thought that Mary was born around 1841. By the time she was five years old, Mary served in the Van Lew household in Richmond, Virginia. The Van Lews owned a hardware store and was one of the wealthiest families in Richmond.

- Mary’s name was listed on the manifest of a ship that left from Sandy Hook, New York to Monrovia, Liberia on December 24, 1855.

- On April 16, 1861, Mary and Wilson Bowser were married at St. John’s Church. They were both described as “colored servants to Mrs. E.L. Van Lew.”

- After the Civil War ended, Mary was a teacher for the Freedmen’s Bureau schools in Virginia, Florida and Georgia. She taught over 200 black children how to read in Richmond.

- Mary gave a series of talks in New York about her spy work during the Civil War (at both the Abyssinian Baptist Church in Manhattan and the African Methodist Episcopal Church in Brooklyn).

- When she was 26 years old, Mary resigned as a teacher with the Freedman’s Bureau. Most people think she moved to the West Indies to be with her new husband (in 1867). And this is where the historical record of her life ends.

- Ted Lange wrote a play about Mary’s life, called “A Lady Patriot” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PhyxrNAPqLg)

- Mary’s incredible life was featured in a novel by Lois Leveen called The Secrets of Mary Bowser.

Want to Know More?

Abbott, Karen. Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy: Four Women Undercover in the Civil War. New York: Harper, 2014.

Leonard, Elizabeth. All the Daring of the Soldier: Women of the Civil War Armies. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1999.

Leveen, Lois. “Mary Richards Bowser (fl. 1846-1867).” Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, 6 March 2018 (http://www.EncyclopediaVirginia.org/Bowser_Mary_Richards_fl_1946-1867).

Van Lew, Elizabeth. A Yankee Spy in Richmond: The Civil War Diary of “Crazy Bet” Van Lew. Edited by David D. Ryan. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stockpole Books, 1996.

Varon, Elizabeth. Southern Lady, Yankee Spy. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Waller, Douglas. Lincoln’s Spies: Their Secret War to Save a Nation. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2019.

Zeinert, Karen. Elizabeth Van Lew: Southern Belle, Union Spy. Parsippany, NJ: Dillon Press, 1995.