Super Scientist

She borrowed a car from a friend to get to a job interview, and didn’t know that she was embarking on an “out of this world journey” from math to the moon. Settle in to your front row seat to the 1960s Space Race and meet rocket scientist Mary Golda Ross…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

Mary Golda Ross looked up from her desk at Lockheed Missiles & Space and saw it was nearly 11:00 p.m. She was working late again on the complex calculations required for two spacecraft to successfully meet up in outer space in preparation for Gemini XII, NASA’s last Gemini Project mission.

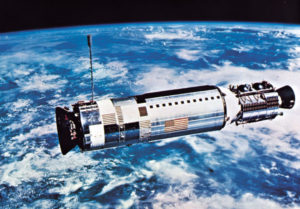

The Agena that was launched during the Gemini XII mission (NASA)

Mary was tired, but happy. She had been dreaming of sending probes and people into space ever since she took her first astronomy classes in graduate school. She didn’t speak of it when she was hired at Lockheed because “if I had mentioned it in 1942, my credibility would have been questioned.”

But now, in 1966, the world had changed. The “Cold War” between the United States and Soviet Union had them competing to be the first country into space. The United States evened the score in the “Space Race” by successfully launching its first astronaut in May 1961. Soon after, President Kennedy vowed that the United States would be the first to the moon, and would get there by 1970.

This didn’t leave enough time for NASA to develop a rocket powerful enough for a round trip to the moon. Instead, it began planning a two stage trip with a main command spaceship orbiting the moon and a smaller lunar vehicle flying round trip to the moon from there. Locating and docking with a spacecraft already in orbit had never been done before, so NASA designed a series of missions, called the Gemini project, to perfect these maneuvers. NASA needed a practice target for the astronauts and Lockheed said it could adapt its Agena rocket, initially designed for military use, for space travel.

Mary had been part of the Agena team for years and was thrilled with the shift in focus to space exploration. Since the Gemini project began, Mary spent many late nights calculating the transfer orbits for the Agena as its left Earth’s atmosphere, mapping the Agena location in space so the astronauts could find it. Tonight was less stressful because the most recent mission, Gemini XI, had been so successful. The astronauts found the Agena on their first orbit and docked without issue. They restarted the Agena engines and moved to an orbit at record high altitude, took a few spins and then returned to the initial orbit. Gemini XII would provide extra practice, but Gemini XI proved the moon landing was within realistic reach.

Mary had been part of the Agena team for years and was thrilled with the shift in focus to space exploration. Since the Gemini project began, Mary spent many late nights calculating the transfer orbits for the Agena as its left Earth’s atmosphere, mapping the Agena location in space so the astronauts could find it. Tonight was less stressful because the most recent mission, Gemini XI, had been so successful. The astronauts found the Agena on their first orbit and docked without issue. They restarted the Agena engines and moved to an orbit at record high altitude, took a few spins and then returned to the initial orbit. Gemini XII would provide extra practice, but Gemini XI proved the moon landing was within realistic reach.

Mary enjoyed the success of Gemini XI all the more for the failures that came before it. During Gemini VI, the first mission with the Agena, its engine exploded before it reached its orbit. During Gemini VIII, the astronauts successfully docked with the Agena, but started spinning uncontrollably and had to use reentry thrusters to detach and return home early. During Gemini X, the astronauts didn’t find the Agena until the 4th orbit due to an orbit error. They were able to dock, but had to cut the mission short to ensure they had enough fuel to return to Earth.

Ad Astra per Astra by America Meredith (Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian)

As Mary walked out of the office, she wished it wasn’t too late to call her family and friends to share how close NASA was to getting to the moon. Much of the military work she did was classified, but she knew that the eventual moon landing would be one of her public legacies.

The Power of the Wand

Mary blazed a trail through the traditionally male dominated field of rocket science. She also devoted considerable time to organizations that encouraged girls to consider a career in engineering. Today, Caeley Looney is following in her footsteps. Caeley is an aerospace engineer who works as a satellite mission analyst at Harris Corporation. In 2019, at age 22, she co-founded Reinvented Magazine, the nation’s first print magazine for women in STEM.

The mission of Reinvented is to remind girls that there is room for them: “the general notion of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics as being predominantly masculine fields is something that has needed to change for a long time now, but there’s really only one way to truly change something – and that’s to reinvent it.” Check out Caeley and Reinvented on Instagram.

Her Yellow Brick Road

After the United States entered World War II, Mary wanted to support the war effort. Her dad suggested that she find a way to lend her math and science skills to the cause. Soon after, Mary was visiting a friend in southern California near Lockheed Martin, one of the biggest manufacturers of military airplanes.

Designing planes that were fast and durable enough for combat required a precise balance of the four principles of flight: lift, weight, thrust and drag. Engineers needed mathematicians, nicknamed “human computers,” to do physics calculations to ensure the best combination of airplane shape and materials. Mary borrowed a car from her friend, drove out to Lockheed and interviewed for one of these positions. She was hired and was one of two women working there during the war. There were no portable electronic calculators, so she did most of her work by hand, with some help from a slide rule and Friden mechanical calculator.

Designing planes that were fast and durable enough for combat required a precise balance of the four principles of flight: lift, weight, thrust and drag. Engineers needed mathematicians, nicknamed “human computers,” to do physics calculations to ensure the best combination of airplane shape and materials. Mary borrowed a car from her friend, drove out to Lockheed and interviewed for one of these positions. She was hired and was one of two women working there during the war. There were no portable electronic calculators, so she did most of her work by hand, with some help from a slide rule and Friden mechanical calculator.

Mary was assigned to the design team for the P-38 Lightning fighter jet. The P-38, designed in 1940, had been rushed into production because it was a rare combination of large and fast. It could go over 1000 miles without having to refuel and its top speed was 400 miles per hour, 100 miles per hour faster than any other fighter jet. At that speed, a plane can break apart in midair if it isn’t flexible enough. Sure enough, a major design flaw soon became apparent. The P-38 became unstable when it went into a dive, putting pilot lives at risk. Mary and her team fixed the problem, and the P-38 became a key element of the Allies’ victory in Europe and the Pacific.

The manager of Lockheed’s aerodynamics group was impressed by Mary’s analytical skills and asked if she was interested in becoming an engineer. She wanted to be more involved in design decisions so said yes, took an accelerated training course in aeronautical engineering, and worked as an apprentice engineer for the rest of the war. After the war, she spent her evenings taking aeronautical engineering classes at UCLA, and received her professional engineering certification in 1949.

Photo via Google, Courtesy of Evelyn Ross McMillan

In 1952, Lockheed invited 40 engineers, including Mary, to start a top secret “think tank” with the mission of “building the world’s most experimental and breakthrough technologies in absolute secrecy at a pace impossible to match.” Mary was the only woman and only American Indian. Lockheed rented a circus tent for them to have space to work. The tent was staked upwind of a smelly plastics factory and soon got the nickname “Skunk Works.”

The initial focus of Skunk Works was developing missile systems and orbiting satellites for the military. Leaving earth’s atmosphere presented special challenges. A rocket has to carry its own oxygen to burn fuel, but needs to stay light enough for its engines to lift. To solve this problem, the engineers designed rockets in “stages.” Lower stage rockets carry and burn the fuel needed for a successful launch and then fall away. Upper stage rockets then use their own fuel source, thrusters, and navigation controls to get to the targeted orbit.

2019 $1 coin honoring Mary (Native American Coin Series, U.S. Mint)

Mary worked on the team developing operational requirements for the Agena, an upper stage rocket commissioned by the Air Force. The stakes were high, because a rocket has only one chance to work. “I was working on designing vehicles that had never been dreamed of before — I felt immense satisfaction in this.”

Brains, Heart & Courage

Mary spent her childhood in a Cherokee community in Park Hill, Oklahoma. Her family had migrated there in the 1830s, when the federal government forced the Cherokee to move west on the Trail of Tears. Many Cherokee leaders, including Mary’s great-great-grandfather Chief John Ross, settled in Park Hill, and it became a center of Cherokee culture.

Mary in the middle of her siblings (Talequah Daily Press)

According to Cherokee legend, their people came from the cluster of stars known as the Pleiades, and came to earth seeking light and knowledge. Cherokee elders prized education and believed that boys and girls should be provided equal opportunities to learn. Mary, nicknamed “Gold” by her family, learned to read when she was very young by sitting on her dad’s lap and listening to him teach her older sister. She enjoyed her math lessons because they felt like a fun game. She loved learning and skipped a grade in her local elementary school.

Mary moved in with her grandparents in a neighboring town to attend high school and walked four miles each way to class. Mary loved math and science and took as many classes in those subjects as possible. Since girls were usually steered toward traditional “feminine subjects” like language and home economics, Mary was often the only girl in her classes.

Mary’s 1928 college yearbook photo (Talequah Daily Press)

Mary graduated in 1924. She was just 16 and felt she had more to learn. She applied for admission at Northeastern State Teachers College, was accepted, declared a math major, and again was the only woman in class. The men wouldn’t sit by her, so she sat alone on one side of the room with all the men on the other. She graduated four years later with a degree in Math and Cherokee Cultural Heritage.

Mary’s first job after college was as a high school math and science teacher at small schools in Oklahoma during The Great Depression. She struggled to make ends meet and discovered she could double her salary by working for the federal government. She took the civil service exam, passed, and got a job doing statistics for the Bureau of Indian Affairs in Washington, D.C.

When Mary decided to get her master’s degree in math, she needed a job that would allow her time for classes and studying. She found a position as a resident adviser at an American Indian boarding school for artists in New Mexico. She spent her summers at Colorado State Teachers College and took her first astronomy classes there. She developed a passion it and enrolled in as many as she could fit into her schedule.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- Mary was born on August 8, 1908 in Park Hill, Oklahoma.

- Mary was the first American Indian woman engineer and one of the first women rocket scientists.

- Mary helped design the Poseidon and Trident submarine launched missiles for the Navy.

- Mary was one of the authors of the NASA Planetary Flight Handbook which provided guidance on space travel to Mars and Venus. She researched and helped design space probes to study those planets and analyzed trajectory for a Mars fly by missions.

- The lessons learned during the Gemini project were also used in assembling the International Space Station.

- Mary appeared on the television show What’s My Line in 1958. The show featured a celebrity panel guessing a mystery guest’s occupation. It took them a long time to guess rocket scientist for Mary because nobody expected a woman to be one.

- After Mary retired in 1973, she became part of the American Indian Science and Engineering Society and the Council of Energy Resource Tribes. She devoted her energy to encourage young women to study engineering.

- Mary cofounded the Los Angeles chapter of the Society of Women Engineers. They set up a scholarship in her honor in 1992.

- Mary was inducted into the Silicon Valley Engineering Council Hall of Fame in 1992.

- Mary walked in the procession at the 2004 opening ceremony for the Smithsonian Museum of the American Indian. She left the Museum $400,000 for its endowment in her will.

- Mary is the subject of a painting by Cherokee artist America Meredith that is hanging in the Smithsonian Museum. The painting synthesizes Mary’s science with her heritage, depicting the Agena rocket alongside a seven pointed star. The number seven is very important to the Cherokee, as it symbolizes the Seven Sisters constellation, the seven clans of the Cherokee Nation and the seven directions in Cherokee cosmology.

- Mary was featured on a $1 coin commemorating the 50th Anniversary of the Moon Landing. The equation on the coin is a formula used to help determine the velocity a rocket needs to leave earth’s atmosphere.

- Mary died on April 29, 2008 at age 99.

Want to Know More?

Agnew, Brad. “Cherokee Engineer A Space Exploration Pioneer,” Tahelquah Daily Press (Mar. 27, 2016)

Agnew, Brad. “Golda Ross Left Teaching to Support War Effort,” Tahelquah Daily Press (Mar 20, 2016)

Blakemore, Erin. “Google Doodle Honors Little Known Math Genius Who Helped America Reach the Stars,” Smithsonian Magazine (Mar. 29, 2017)

Hacker, Barton C. & Gimwood, James, M. “On the Shoulders of Titans: A History of Project Gemini” (NASA 1977)

Krol, Debra Utacia. “Mary Golda Ross Marking “Firsts” in Aerospace,” Winds of Change (American Indian Science & Engineering Society Sept. 1, 2017)

Ouimette-Kinney, Mary. “Mary G. Ross,” Biographies of Women Mathematicians (Agnes Scott College July 10, 2016)

Rumerman, Judy A., Human Space Flight: A Record of Achievement, 1961-1998

Sandberg, Ariel “Remembering Mary Golda Ross,” The Michigan Engineer News Center (June 14, 2017)

Sheppard, Laurel M. “An Interview with Mary Ross: First Native American Woman Engineer Aerospace Pioneer Returns to her Native American Roots” (Lash Publications Int’l)

Smith, Betty “Pure ‘Cherokee’ Gold,” Tahlequah Daily Press (June 26, 2008)

Viola, Herman, “Mary Golda Ross: She Reached for the Stars,” Smithsonian Museum of the American Indian Magazine (Winter 2018)

Williams, Dr. David R., “The Gemini Program (1962-1966),” (NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Dec. 30, 2004)