Health Hero

They called her a “medical monstrosity” simply because she was a doctor who happened to be a woman. Take a trip to the Civil War era to meet Mary Edwards Walker…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

Dr. Mary Edwards Walker stood alone before the men of the Union Army medical review board. It was March 6, 1864, she was 32 years old, and one of the only woman doctors in the country. Mary had been volunteering in military hospitals in Washington, D.C. and the front lines since the Civil War began nearly three years earlier.

Mary had recently arrived in Chattanooga, Tennessee to treat soldiers wounded in battles along the Confederate border. She had a letter from the Assistant Surgeon General recommending that she be given a formal Army appointment as an assistant surgeon. Her appearance before the review board was the last step of a long road toward becoming an official Army surgeon, with the rank and pay she deserved.

Mary wearing the controversial “Bloomer” outfit of a skirt over pants. (National Archives)

From the start of the board’s questioning, Mary was treated with contempt. The male doctors were immediately put off by her attire. As usual, Mary wasn’t dressed in the traditional confining corsets and large hoop skirts. Instead, she wore pants, with a split skirt over them, an outfit which gave her the mobility she needed to be an effective doctor.

Mary was well prepared. She brought her medical school diploma from Syracuse Medical College and her graduate certificate from the Hygeia Therapeutic College. She had reference letters praising her surgical skills from Army doctors she had worked beside at military hospitals in Washington, D.C. and near the front lines. But it soon became clear that the examiners had already decided that they would not allow a female surgeon to join their ranks.

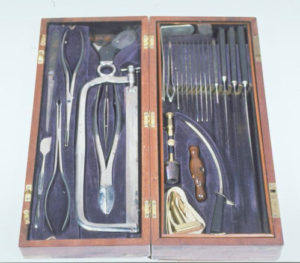

They refused to ask her questions about treating battle injuries and diseases. Instead, they made a point of only asking questions about women’s bodies, implying that it was improper for Mary to know anything about men. Mary persisted by answering questions with references to her military doctoring experience. While traditional medical practice was pro-amputation, even for simple flesh wounds, Mary had found a better way. She described her efforts to keep wounds clean and patients hydrated so they could heal while keeping their injured limbs attached.

The board didn’t approve of Mary. They variously described her as a “medical monstrosity,” possessing “utter ignorance,” having “no more medical knowledge than an ordinary housewife,” and being “entirely unfit for the position of medical officer.” Some refused to believe she had studied medicine. They said she should only be allowed to serve as a nurse.

Finally, Mary had seen and heard enough. She told the examiners that if they did not assign her to duty “without any more insult,” she would make her case directly to the senior officer in charge, General Thomas. They were not moved, and rejected her application.

Mary went directly to General Thomas. He had observed Mary’s medical skill and needed an immediate replacement for a doctor who had died. He ignored the board and approved Mary’s appointment as an Acting Assistant Surgeon on March 11, 1864 — only three days after the Board rejected her. Although Mary remained a civilian, she was given a rank similar to a lieutenant and finally paid for her work.

The Power of the Wand

Mary grew up in an era when society tried to control women by telling them what they could do and what they could wear, Mary achieved her dream by never letting the people who told her “no” have the final word. Similarly inspiring is Dr. Sasha Shillcut, an anesthesiologist and founder of Brave Enough, Brave Enough is an organization devoted to encouraging women to take control of their professional and personal lives. Dr. Shillcut also hosts a Facebook group, Style MD, that provides support and encouragement to over 10,000 women doctors.

Her Yellow Brick Road

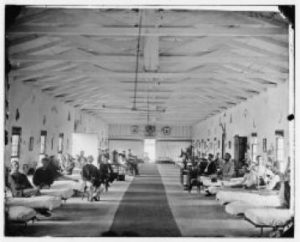

Civil War patients inside the Armory Square Hospital in Washington D.C. (Library of Congress)

After tensions between the North and South finally exploded into the Civil War in 1861, Mary went to the Union Army offices in Washington, D.C. and applied to be an Army surgeon. The Army said no because women were only allowed to serve as nurses assisting male doctors. Mary then walked into the Union Army hospital that had been set up at the U.S. Patent Office and volunteered to be an assistant general surgeon. The doctor on duty was overwhelmed with sick and injured patients and agreed.

Most people thought the war would be over quickly, so neither side was well-prepared. The Army didn’t have adequate water or supplies on hand at the front lines. In November 1862, Mary traveled to a makeshift hospital in a barn in Warrenton, Virginia, to help treat the men who had been wounded in the Battle of Antietam earlier that fall. Antietam still ranks as the deadliest day in American military history, and there were thousands of men who needed care. Mary did what she could: she combed the area for food and supplies and even used her own nightgowns to make bandages.

Mary knew many of the men had no chance of survival under the poor conditions. She also knew that any officer she approached would likely ignore or scold her for interfering because she was a woman, but the well-being of the soldiers came first. She confronted General Burnside and told him that the most seriously injured must be moved to the military hospital in Washington, D.C. Mary was so persuasive that the General not only agreed, he asked her to accompany the men on the train and care for them on the way.

Civil War Surgical Kit(National Museum of American History)

Mary went back to the front lines several times, working for free while the male doctors earned hundreds of dollars a month. At each site, the overwhelming number of soldiers needing care overcame the standard objections to a woman doctor. Mary earned the respect of many officers who saw her skill, and they began supporting her efforts to be officially hired by the Army. One of the doctors she worked with after the Battle of Fredericksburg, where the Union suffered over 13,000 casualties, wrote to the Secretary of War asking him to give Mary a commission.

Mary also wrote to the Secretary of War, asking if she could organize her own regiment, as many male surgeons had done. He said no. She also wrote to President Lincoln, asking him to intervene and grant her an Army commission. She pointed out that she had been “denied solely on the ground of my sex” and said she would serve anywhere. Lincoln responded with another no, stating that it wouldn’t interfere in Army medical department decisions. Mary could have posed as a man, as hundreds of women did in order to serve in the military, but she wanted to be recognized for who she was — a woman and a surgeon.

In September, 1863, the Union suffered a major defeat in the Battle of Chickamauga and suffered over 16,000 casualties. They needed more doctors to help treat the wounded, and Mary agreed to go. She persuaded the Assistant Surgeon General to write a letter recommending that she be officially hired by the Army and travelled to Chattanooga.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Mary grew up in Oswego, New York. Oswego was a progressive town, and many of its citizens, including Mary’s family, were “free thinkers” who supported abolition of slavery, women’s rights, health reform, and temperance. Mary was the fifth born of seven children — 6 girls and a baby brother.

Mary’s parents believed that gender shouldn’t determine how people lived their lives. Mary’s mom helped with heavy labor and her dad did some housekeeping. They founded a school on their farm for girls and boys to attend together. They kept a big library of all sorts of books at their farmhouse and encouraged their kids to read.

Mary’s favorite books were the medical texts. She was 15 when Elizabeth Blackwell became the first woman doctor in the United States. Mary wanted to be the second, so at age 17 she followed her sisters to college to study science and health. After graduation, she had to take a teaching job to earn the $165 she needed to pay for medical school. Her options were limited because there were very few schools that would admit women. She chose Syracuse Medical College because it taught a modern approach to medicine and was the only woman in her medical school class.

Glinda’s Gallery

Visit Mary’s digital scrapbook on Pinterest: https://www.pinterest.com/theglindafactor/mary-edwards-walker/

Just the Facts

- Mary was born on November 26, 1832 in Oswego, New York.

- When Mary started working, women were expected to wear heavy dresses with several petticoats, and tight waists and sleeves. This was intended to make it difficult for women to breathe, eat, and move so they would stay close to home. Mary started altering her clothing in the new style designed by Amelia Bloomer, which involved loose pants gathered at the ankles with a short dress or skirt worn over it.

- Soon after Mary graduated from medical school with honors, she married fellow medical student Albert Miller. Mary did not make the traditional promise to obey Albert, wore pants and a fancy coat instead of a dress, and kept her own last name. Mary and Albert went into medical practice together, but most people didn’t trust a woman doctor and Albert was not a good husband. The marriage and practice were over by the time Mary turned 25.

- After her appointment as an official Army surgeon, Mary traveled with the 52nd Ohio Infantry which was stationed along the Tennessee/Georgia border. Mary often crossed over to Confederate territory to treat women and children who needed medical care.

- Mary made her own officer’s uniform of pants and a coat to give her maximum mobility for treating injured soldiers. She was arrested several times for impersonating a man because she refused to wear a skirt over her pants. Each time, she defended herself by saying she had permission from the government to dress this way to be an effective army doctor.

- In April 1864, Mary was captured and held in a Confederate prison for four months. She was released in a doctor prisoner exchange and served the rest of the war as a Medical Director for a women’s prison in Kentucky and at an orphanage in Tennessee.

- For her 3 years of wartime service, she was paid only $766.16. She was given a monthly pension of $8.50, which even when it was later increased to $20 was less than most military widow pensions.

- After the war ended, President Andrew Johnson awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor to Mary on November 11, 1865. This Medal is the United States highest military award, and only about 3500 have ever been awarded. Mary is still the first and only woman to have ever received one. You can read the full text of Mary’s Army Service Record and Congressional Medal of Honor citation from President Johnson here.

- After the war, Mary had to retire from medicine due to the muscular atrophy she suffered while imprisoned. She spent the majority of her time giving lectures supporting equality for women, and writing, including a published a collection of essays on women’s rights titled .

- Mary continued to advocate for dress reform and by the 1870s, had switched to men’s clothes completely, wearing a wing collar, bow tie, and top hat.

- In 1917, near the end of World War I, Congress changed the Medal of Honor standards to require “actual combat with an enemy.” They demanded the medals back from Mary and 910 others. Mary said no, it was hers, she earned it, and she would not give it back. She then wore it every day until her death on February 21, 1919 in Oswego.

- President Jimmy Carter officially restored Mary’s Medal of Honor in 1977, recognizing her “distinguished gallantry, self-sacrifice, patriotism, dedication and unflinching loyalty to her country, despite the apparent discrimination because of her sex.”

Want to Know More?

Gaines, Allison. Mary Edwards Walker: The Only Woman Medal of Honor Recipient. (Cavendish Square Publishing 2018)

Goldmith, Bonnie Zucker, Dr. Mary Edwards Walker: Civil War Surgeon & Medal of Honor Recipient (ABDO 2010)

Johnson, Carla. Civil War Doctor: The Story of Mary Walker. (Morgan Reynolds Publishing 2007)

LeClair, Mary K., White, Justin D., and Keeter, Susan. Three 19th Century Women Doctors: Elizabeth Blackwell, Mary Walker, and Sarah Loguen Fraser (Hofmann Press 2007)

Walker, Dale L. Mary Edwards Walker: Above and Beyond. (Tom Doherty Associates 2005)

Coe, Alexis, Mary Walker’s Request to be Appointed as a Union Doctor in the Civil War, (February 7, 2013)

Lange, Katie, Meet Dr. Mary Walker:The Only Female Medal of Honor Recipient (DOD News, Defense Media Activity March 7, 2017)

Pass, Alexandra R. & Bishop, Jennifer D., Mary Edwards Walker: Trailblazing Feminist, Surgeon and War Veteran (American College of Surgeons 2016)