Passionate Patriot

She came to the United States as a child from China. Seven years later she was a teenage activist on a horse leading thousands of women marching for suffrage in New York City. She spent the next five years marching and speaking until New York finally granted women the vote. And she did this even though she herself would still be barred from citizenship and voting by the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. Step back in time to October 1917 and meet Mabel Ping-Hua Lee…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

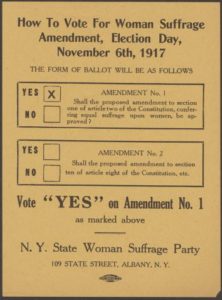

New York Times front page the Sunday before Election Day 1917

Mabel Ping-Hua Lee looked around at her fellow marchers and felt a sense of deja vu. While she now was a 21 year old graduate student, she had participated in her first suffrage parade as a 16 year old high school student. Then, as now, marchers gathered to support an amendment to the New York Constitution giving women the vote. New York, a big state with 6 major newspapers, was central to the suffragettes’ efforts nationwide. If New York gave women the vote, the country was likely to follow.

It was October 20, 1917 and while Mabel was cautiously optimistic, she missed the unbridled optimism she had felt as a teenager. Back in 1912, suffrage parades were gaining popularity as an effective way to gather public support and demonstrate the strength of the movement. Several western states already allowed women the vote. 1911 had been an important year worldwide for suffrage, particularly in China’s new Republic. Momentum was building.

Mabel was featured in the NY Times before the 1912 parade

Suffragettes reached out to the Chinese-American community to get their opinions about the Chinese suffrage movement’s success. And Chinese-Americans welcomed the chance to educate suffragettes about how damaging the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which barred them from becoming American citizens, was to their communities. Mabel made a name for herself during these conversations. Before the parade, the New York Tribune wrote that Mabel’s “refusal to remain silent on the issue of women’s suffrage simultaneously served as a political statement that Chinese Americans refused to be silenced into submission and were active members of political and civil society.”

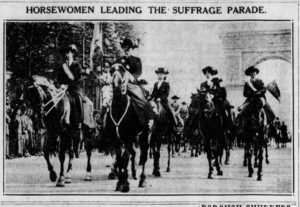

Mabel remembered everything about that evening of May 4, 1912, particularly how proud she felt in her suffragette white dress and tri-corned black hat (adorned with the green, purple and white cockade of the Women’s Political Union!) and how nervous she was handling her horse as part of a 50 woman contingent leading over 10,000 marchers through the streets of New York City. While Mabel couldn’t see them, she knew her mom and other women from the Chinese community were marching together behind her, carrying the new flag of the Chinese Republic with a sign that said “Light from China.” Other suffragettes were hoping to leverage patriotic competition – one of them carried a banner stating “NAWSA Catching Up with China.”

Mabel in the 1912 Suffrage Parade (Brooklyn Daily Eagle)

There were thousands of spectators, many supportive and some there to harass. Although men in the crowd yelled “Who’s minding the babies?” at the women and “Henpecked!” at the handful of men, at the end of the three-mile route, Mabel had been exhilarated and believed change was inevitable and coming soon. The parade was a huge spectacle and received nationwide media attention, with Mabel featured in several articles. The New York Times described her as “the symbol of the new era, when all women will be free and unhampered.”

And now it was over five years later, Mabel was marching again, but the world looked very different. The United States had been fighting in the Great War for 6 months, and among the 20,000 marchers and thousands more spectators were military nurses and factory workers, as well as wives, mothers, and sisters of servicemen – many whom had signs highlighting their patriotism and commitment to the war effort. Mabel was there leading a contingent of residents from nearby Chinatown.

Mabel wondered if this year would finally bring the vote and the wave of déjà vu hit her again, this time with recollections of the suffrage parade two years earlier, just before Election Day 1915. That had been the last time the suffrage amendment referendum had been on the ballot, and the 25,000 participants, 5 mile route, and 100,000 spectators lining the streets had raised hopes that the men heading to the polls two weeks later would vote yes. But the referendum failed, and the suffragettes had to fight to get it on the ballot again in 1917. So Mabel found herself marching again, less than two weeks before Election Day 1917. She didn’t know what would happen, but knew she wouldn’t stop marching until women had the vote.

Mabel wondered if this year would finally bring the vote and the wave of déjà vu hit her again, this time with recollections of the suffrage parade two years earlier, just before Election Day 1915. That had been the last time the suffrage amendment referendum had been on the ballot, and the 25,000 participants, 5 mile route, and 100,000 spectators lining the streets had raised hopes that the men heading to the polls two weeks later would vote yes. But the referendum failed, and the suffragettes had to fight to get it on the ballot again in 1917. So Mabel found herself marching again, less than two weeks before Election Day 1917. She didn’t know what would happen, but knew she wouldn’t stop marching until women had the vote.

The Power of the Wand

On November 6, 1917, women in New York got the vote. It took three more years before the 19th Amendment was ratified and every woman citizen in the United States had the same right. Suffrage was a bittersweet victory for Mabel because she was still barred from the voting booth by the Chinese Exclusion Act. She had worked for years for a cause that didn’t directly benefit her, and hoped that with women voting, the Chinese Exclusion Act would be overturned. It eventually was, but not until 1943.

Mabel’s legacy lives on today in podcasts like Dear Asian Girl, hosted by Alina Rahim, Genesis Magpayo, Melissa Yu, and Naina Giri. Dear Asian Girl’s mission is to uplift, highlight, and support Asian girls everywhere and many of their podcasts are dedicated to discussing politics, elections, and representation. Check out their February 2021 podcast, The Power of Elections, for a discussion about voter suppression and other political challenges in the Asian American community.

Her Yellow Brick Road

During the 1911 Chinese Revolution, Mabel and her parents were living in New York, but still in close contact with family and friends in China. When the new Chinese republic granted women the vote, it reverberated worldwide. Although American suffragettes had been fighting for the vote since before the Civil War, by 1911 only 5 states allowed women to vote.

New York TImes article May 1912

After the New York Legislature rejected a bill to put a suffrage amendment on the 1911 Election Day ballot, local suffragettes decided they needed a new strategy. They reached out to the local Chinese-American community to see if anyone was willing to meet them to talk about the strategies women in China used to get the vote. They were planning a big suffrage march through the streets of Manhattan, and wanted some advice. Mabel, her mom, and two other women agreed to meet the group at the Peking Restaurant in Chinatown.

The meeting took place on a spring day in April 1912. Mabel was 16, a high school senior, and had just been accepted to Barnard College in New York City. She shared with the white women what it was like to be a minority teenager fighting for change. She emphasized the need to improve equal access to education, which in her view was necessary for women’s rights and democracy to succeed. The suffragettes were impressed with this poised and persuasive teenager and asked her to join the group of women leading the parade route on horseback. Although Mabel, as a city girl, didn’t spend much time on a horse, she agreed to do it.

Mabel in the Barnard/Columbia Chinese Students Alliance 1915 (Library of Congress)

After her experience in the 1912 parade, Mabel was inspired. She began her college studies determined to use her talents and access to fight for the vote. She was one of only four Chinese students at Barnard, but it was a “sister” school to all male Columbia and the two schools shared many clubs, including the Chinese Students’ Alliance. Mabel joined the Alliance and wrote several essays for the its magazine, The Chinese Students’ Monthly. One of her first, written when she was just 17, she titled “The Meaning of Woman Suffrage.” In it, Mabel declared that the feminist movement and women’s suffrage were not an outlandish idea, but simply “the application of democracy to women.”

Mabel explained her view that democracy has “four stages to its development, like four waves, one rolling into another. They are: first, moral, religious or spiritual; second, legal; third, political; and, fourth, economic.” The first was settled through Jesus’ statement that “slaves had as much as princes in the sight of God” and the second by the concept of equal rights before the law established in the Magna Carta. Mabel then argued that the vote and economic independence for women would stabilize democracy, analogizing western civilization to a house that left “every other beam loose in its construction by leaving out its women.”

Mabel shared these ideas in a speech to the Women’s Political Union’s Suffrage Shop, who invited her to speak in early 1915. Mabel emphasized to her audience that throughout history, society claims that women aren’t capable of something, women do that thing, and prove the conventional wisdom wrong. Society then moves on to its next claim of female incompetence and the patten continues. Once women could read and write, the issue was high school, then college, graduate school, opening a business, etc. Mabel gave a pragmatic definition of feminists, that they “want nothing more than the equality of opportunity for women to prove their merits and what they are best suited to do.”

Mabel shared these ideas in a speech to the Women’s Political Union’s Suffrage Shop, who invited her to speak in early 1915. Mabel emphasized to her audience that throughout history, society claims that women aren’t capable of something, women do that thing, and prove the conventional wisdom wrong. Society then moves on to its next claim of female incompetence and the patten continues. Once women could read and write, the issue was high school, then college, graduate school, opening a business, etc. Mabel gave a pragmatic definition of feminists, that they “want nothing more than the equality of opportunity for women to prove their merits and what they are best suited to do.”

The event received a lot of media coverage, including in the New York Times, and Mabel was in demand as a public speaker on suffrage and women’s rights. Later in 1915, in her speech “The Submerged Half,” Mabel argued that “no nation can ever make real and lasting progress in civilization unless its women are following close to its men if not actually abreast with them.”

Brains, Heart & Courage

Mabel spent her early childhood in Guangzhou, China, a big port city about 85 miles northwest of Hong Kong. Her father was a Baptist minister and when Mabel was just a toddler, he left to serve as a missionary in the United States. While the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 banned most Chinese laborers from entering the country, Chinese clergy were allowed into the country under certain circumstances. However, like other Chinese immigrants, they were barred from becoming American citizens.

Mabel in the early 1900s (Library of Congress)

Mabel and her mom had to stay behind and wait until they could get permission to join him. They lived with Mabel’s grandmother, and Mabel attended a school for missionary children in Hong Kong. She learned English at school. and she and her mom were finally able to join her dad in New York City in 1905. He was working as the pastor of the Morning Star Mission and very involved in neighborhood politics. They lived in a tenement in Chinatown.

Mabel attended school at Erasmus Hall Academy in Brooklyn. Erasmus Hall was the oldest public school in the nation, but had been about to close until it was needed to accommodate all the immigrant children arriving with their parents. Mabel was one of just a few Chinese children at the school, and the only one in her graduating class. She was a good student who particularly excelled in English, Latin, and math.

Mabel’s parents had progressive views about women and education. Mabel’s mom had been raised in a very traditional Chinese home where her feet had been bound to make them small and feminine. The years leading to the Chinese Revolution had involved much debate about women’s rights and the role they should and could play in a new society.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- Mabel was born in either 1896 or 1897 in Guangzhou, China.

- Mabel earned a Master’s Degree from Columbia Teachers’ College in Educational Administration.

- Mabel was the first Chinese woman to earn a PhD in Economics in the United States, graduating from Columbia University in 1921. She published a 500 page dissertation The Economic History of China: With Special Reference to Agriculture. She was awarded a Boxer Indemnity Scholarship for graduate school because the Chinese government was impressed with her agricultural research.

- Mabel planned to move back to China after completing her education to open a girls’ school and get involved in politics. But when her dad died in 1924, she decided to stay in the United States and step into his role as Director of Mission at the Morning Star Mission. In 1926, the mission officially incorporated as the First Chinese Baptist Church of New York City.

- Mabel worked with the Baptist mission societies to raise money in her father’s honor for a new building to house a church and community center. They purchased 21 Pell Street. After a few years of wrangling about renovations and title to the property, Mabel opened the Chinese Christian Center became an important community center resource, offering a health clinic, job training, English classes for all ages, and a kindergarten. The church and community center became independent from the national Baptist church in 1954. Mabel remained lead pastor until her death, although she never was ordained as a minister.

- Mabel was a gifted businesswoman. She invested in real estate and worked as a consultant to the wealthy Rockefeller family. Her fur coat and Rolls-Royce became her signature look.

- The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was overturned in 1943, allowing all Chinese immigrants to become American citizens at last.

- Mabel died in 1966 at age 70.

- The post office around the corner from the First Chinese Baptist Church was re-named the Mabel Lee Memorial Post Office in 2018. Rep. Nydia Velázquez at the dedication ceremony observed that “At a time when women were widely expected to spend a life in the home, Lee shattered one glass ceiling after another. From speaking out in the classroom to organizing Chinese American women to secure the right to vote, Lee’s bold vision for Chinatown is very much alive in our community today.”

Want to Know More?

Cahill, Cathleen D. Recasting the Vote: How Women of Color Transformed the Suffrage Movement (UNC Press 2020).

Alexander, Kerri Lee. “Mabel Ping-Hua Lee” (National Women’s History Museum 2020).

Brooks, Charlotte. “Suffragist Landmark.” Asian American History in NYC: Finding the Asian American Past in the Five Boroughs (Aug. 25, 2014).

Cahill, Cathleen. “Mabel Ping-Hua Lee: How Chinese-American Women Helped Shape the Suffrage Movement” (updated Dec. 14, 2020).

Hond, Paul. “How Columbia Suffragists Fought for the Right of Women to Vote” (Columbia Magazine Fall 2020).

Li, Grace. “Chinese Girl Wants Vote”:The Asian-American Suffragette Mabel Ping-Hua Lee” (University of Alberta).

Samson, Kari. “Meet the First Chinese American Woman to Fight for Voting Rights that History Almost Forgot” (Nextshark Nov. 6, 2019).

Staff. “Dr. Mabel Ping-Hua Lee” (National Park Service).

Tseng, Timothy. “Asian American Legacy Dr. Mabel Lee” (timtseng.net Dec. 12, 2012).

Tseng, Timothy. “Dr. Mabel Lee: The Intersticial Career of a Protestant Chinese American Woman, 1924-1950” (Denver Seminary 1996).