Passionate Patriot

Imagine watching your country celebrate freedom with a statue of a woman when its living, breathing women citizens weren’t even allowed to vote. Travel back to 1886 and board a stinky barge in New York Harbor to join Lillie Devereaux Blake’s protest of the Statue of Liberty’s Dedication Day.

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

Lillie Devereaux Blake wrinkled her nose as she looked at the John Lennox, a two-level cattle barge. It stank! The decks of the barge were still covered in manure from its regular passengers, despite the fact that the owner had promised to clean it. But Lillie didn’t let that stop her — she held a kerchief over her nose and marched aboard. Luckily, 200 women followed her (including Lillie’s daughter).

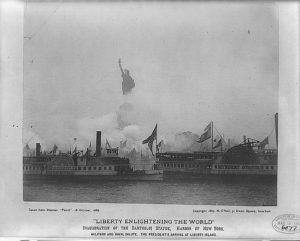

It was October 28, 1886 — Dedication Day for the Statue of Liberty, which was a gift from the people of France to the people of America. The events included a parade down Broadway Street, a maritime parade in New York Harbor, and finally a ceremony on Bedloe’s Island. In fact, it was one of the largest celebrations in New York City’s history.

Lillie and her friends were determined to point out the greatest hypocrisy of the day — a woman was chosen to represent the ideal of Liberty even though women had few legal rights in America. Back then, only men had the freedoms that the Statue of Liberty was designed to celebrate.

It was a cold and rainy day. And the John Lennox was less than ideal — it had slippery decks, no chairs, no heat, and no way to escape the elements. The women were uncomfortable the entire time. But that was a small price to pay for the opportunity of a lifetime.

It was a cold and rainy day. And the John Lennox was less than ideal — it had slippery decks, no chairs, no heat, and no way to escape the elements. The women were uncomfortable the entire time. But that was a small price to pay for the opportunity of a lifetime.

After everyone was on board, the John Lennox slowly pulled away from the West Twenty-First Street Pier, then headed down the Hudson River and into New York Harbor. It was tricky, since the barge had to weave its way through the floating celebration. Luckily, the John Lennox was able to squeeze between two military ships and anchor right at the base of the Statue of Liberty.

New York Harbor was filled with over 300 boats — French and American warships, steamers, tugs, yachts, ferries, and boats of every other shape and size. One by one, each boat anchored in its designated spot and waited for the ceremony to begin.

Whistles sounded from every direction. Bands played. Guns fired. It was a symphony of noise! And many boats were covered in red, white and blue decorations (conveniently, the colors of both the American and French flags).

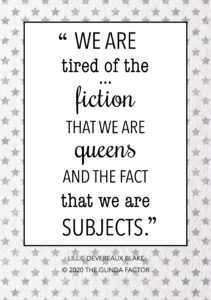

Lillie and her friends seized their moment to protest the lack of liberties granted to women in America. And they did anything to get their message across. They hung banners and flags from the railings. They waved signs in the air (Lillie’s said “American women have no freedom”). They shouted into megaphones. They sang songs. And they gave speeches. They even adopted an official protest statement:

Lillie and her friends seized their moment to protest the lack of liberties granted to women in America. And they did anything to get their message across. They hung banners and flags from the railings. They waved signs in the air (Lillie’s said “American women have no freedom”). They shouted into megaphones. They sang songs. And they gave speeches. They even adopted an official protest statement:

In erecting a Statue of Liberty embodied as a woman in a land where no woman has political liberty, men have shown a delightful inconsistency which excites the wonder and admiration of the opposite sex.

The women grew silent when the French flag dropped to the ground and the statue’s face was revealed. Lady Liberty was a magnificent sight and gave Lillie the hope that women would eventually achieve the same rights as men.

The Power of the Wand

Lillie was tireless in her support of the idea that women should be treated fairly under the law. She advocated for more than the right to vote — she wanted equality for women in all areas (education, social, political and economic). And every generation of American women has benefited from Lillie’s work.

Thanks to the efforts of Lillie and many others, women were finally granted the right to vote in 1920. Achieving the right to vote is only half the battle, however. To bring about change, people need to cast their ballot and get involved.

Winter Breeanne Minisee is dedicated to educating young people about the importance of voting and becoming politically active. She is active in a number of organizations, including Youth Empower and #PowerToThePolls. She also started a program, Power Future Voters, that introduces the importance of civic engagement to elementary students. And she is founder and CEO of Just Active, an organization that supports political involvement by young people.

Her Yellow Brick Road

Lillie spent much of her adult life consumed with the fight for women’s equality. Her views seemed radical at the time, however. And they cost her dearly — she lost many of her childhood friendships; her family refused to talk to her; and she was excluded from “society.”

Lillie was methodical in her work to gain political power for women. She wrote letters, published articles, rented halls for meetings, raised money and gave speeches. And she was good at it — Lillie traveled across the country speaking out in favor of women”s rights.

Lillie was also active in women’s rights organizations at both the national and local level. She was a respected leader in the movement in New York, serving as president of both the New York State Women’s Suffrage Association (NYSWSA) and the New York City Woman’s Suffrage League for many years.

Lillie was also active in women’s rights organizations at both the national and local level. She was a respected leader in the movement in New York, serving as president of both the New York State Women’s Suffrage Association (NYSWSA) and the New York City Woman’s Suffrage League for many years.

In fact, Lillie was president of the NYSWSA when she organized the protest at the Statue of Liberty. She shared her idea at a meeting of the Executive Committee in her home on October 10. The other women were enthusiastic about the idea and threw themselves into planning the protest. The NYSWSA had only $4 in the bank, however. And the cheapest boat available was the John Lennox, at $100 per day. So they needed to raise some cash.

The women decided to sell tickets to board the John Lennox and participate in the protest. The tickets were sold at a woman’s suffrage event the afternoon before Dedication Day. There were 200 tickets, at $1 each. And they sold out in no time — for most women, it was the only way to be part of the historic event.

Lillie had to get permission for the NYSWSA to participate in the Dedication Day events. She initially requested tickets for the ceremony itself on Bedloe’s Island, but was denied because they were “unaccompanied women.” So, Lillie applied to join the maritime parade and be assigned a spot in New York Harbor. She breathed a sigh of relief when her request was approved — their protest could become a reality.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Lillie grew up in New Haven, Connecticut, a vibrant college town. While there, she witnessed Yale University students participating in debates, demonstrations, and riots about a variety of social issues. And they made an impact on her.

Lillie enjoyed writing fictional stories from an early age. It was just a hobby for years. But then, her husband died and she needed to support herself and two children. So Lillie moved to Washington DC during the Civil War and was hired as a correspondent for various New York newspapers — she wrote about DC, social and political events, and the Union cause. Lillie rarely wrote under her own name, however, since it wasn’t socially acceptable for a woman to have a career back then. Sometimes she used a pseudonym, and other times she published her work anonymously.

After Lillie remarried, she had the luxury to pursue her passion of women’s equality. She started by trying to change the laws that affected women at the state level, particularly in her home state of New York. And she achieved her first legislative success in 1880 — the New York state legislature finally allowed women to serve on school boards and vote in school board elections.

After Lillie remarried, she had the luxury to pursue her passion of women’s equality. She started by trying to change the laws that affected women at the state level, particularly in her home state of New York. And she achieved her first legislative success in 1880 — the New York state legislature finally allowed women to serve on school boards and vote in school board elections.

The success encouraged Lillie to think bigger. She gathered thousands of petitions in favor of suffrage; she requested that women be exempted from paying taxes until they could vote; she drafted legislation; and she educated women across America. Before long, nearly everything Lillie did was in furtherance of women’s quality.

Glinda’s Gallery

Visit Lillie’s digital scrapbook on Pinterest: https://www.pinterest.com/theglindafactor/lillie-devereaux-blake/

Just the Facts

- Lillie was born on August 31, 1833 into a wealthy family from Raleigh, North Carolina. They moved to New Haven, Connecticut after Lillie’s father died.

- She attended a private school and took lessons in French, piano, art and dancing. Then, she was tutored by a Yale University graduate student, who taught her subjects based on the Yale undergraduate curriculum.

- Lillie married Frank Umsted, who was a lawyer, on June 20, 1855. They had two daughters (Elizabeth and Katherine). He spent all her inheritance within a few years, however, then committed suicide.

- Lillie had a successful writing career for many years. Lillie wrote seven novels, two collections of short stories, and nearly 500 essays. Her fictional stories were printed in more than 50 different newspapers and magazines.

- Lillie married a second time to Grinfill Blake in 1866, when she was 33 years old. They were married for 30 years.

- Lillie contributed to Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s book, The Women’s Bible. She also signed the Declaration of the Rights of the Women of the United States and was one of the women who presented it, in protest, at the 1876 Centennial celebration in Philadelphia.

- Lillie was president of the New York State Women’s Suffrage Association from 1879 to 1890.

- For five years, Lillie oversaw legislative affairs for the National Woman’s Suffrage Association. Lillie had different goals than Susan B Anthony, however, and eventually dropped her membership in the NWSA.

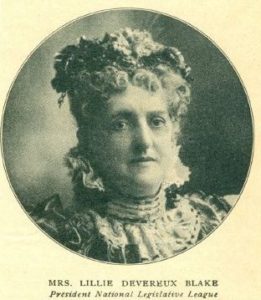

- Then, Lillie went on to form the National Legislative League in 1900. The League tracked bills before Congress and state legislatures that affected the rights of women.

- Lillie continued to be a champion of women’s rights until she died from tuberculosis at age 80, on December 30, 1913 in Englewood, New Jersey.

Want to Know More?

Blake, Katherine Devereaux. Champion of Women, The Life of Lillie Devereaux Blake. New York: Fleming H. Revell Company, 1943.

Farrell, Grace. Lillie Devereaux Blake: Retracing a Life Erased. Amherst and Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 2002.

Gilder, Rodman. Statue of Liberty Enlightening the World. New York: New York Trust Company, 1943.

“Goddess of Liberty.” Wichita Eagle, October 29, 1886. Volume 5, No. 140.

The Lillie Devereaux Blake Papers are held at the Missouri History Museum and the Blake Family Papers are held at the Smith College Library.