Amazing Artist

She merged her artistic talent with her passion for bringing attention to the overlooked. With concrete as her canvas and an imagination as big as the world, she gathered together teams of artists, historians, and at-risk youth to create some of the most powerful urban murals our cities have ever seen. Travel back to 1984, step under an overpass on Los Angeles’ 110 Freeway, and meet Judy Baca…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

Judy Baca took a step back to inspect her latest work in progress, a mural to commemorate the upcoming 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles. She was standing under the overpass connecting 4th Street to the 110 freeway.

Judy in front of The Great Wall of California (UCLA).

Los Angeles was known for its colorful murals, and its community of urban artists, many whom were Mexican-American, were putting an American spin on Mexico’s rich tradition of murals as social commentary. Los Angeles’ murals, with their incorporation of art from many different cultures, reflected America’s melting pot. Judy attributed the power of the Los Angeles mural movement to the city’s expanses of concrete, good weather, and most importantly, a large population of immigrants who felt invisible and wanted to express themselves.

Olympic organizers were excited to reintroduce Los Angeles to the world, and devised a plan for 10 new murals by 10 different artists. Judy, already well-known for designing the landmark “Great Wall of California” was one of them. Judy agreed, excited for another opportunity to use art to bring attention to the overlooked. She began researching and found many stories about athletes from marginalized communities who became Olympians without much financial or organizational support.

“Hitting the Wall” (SPARC)

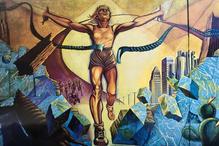

Judy became intrigued by women marathoners, who were competing in the Olympics for the first time. For years, the marathon had been considered too dangerous for women to even attempt. Judy was inspired by their fight for the right to compete and decided to a woman runner would be the centerpiece of her mural. She met with many women marathoners and they all had stories about “hitting the wall.” Between miles 20 and 24, a runner’s muscles often run out of stored energy and begin shutting down, and she has to rely on her mental strength and determination to keep moving.

Breaking through the wall (SPARC)

This phenomenon inspired Judy to design a mural with a 30 foot tall woman runner bursting through a giant marble wall, to honor the obstacles women overcome to realize their dreams, whether they are Olympic champions or artists. Judy included a depiction of the Tower of Babel falling down, which symbolized a return to a universal understanding that female achievement should not be limited.

Taking the mural from design to the freeway wasn’t an easy task. Although Judy, like the other artists, was paid $15,000, she barely had enough to break even after spending thousands of dollars on barriers and insurance to keep her painters and passing drivers safe during the nine months of work to complete the mural. Judy named her mural “Hitting the Wall.”

The Power of the Wand

Judy believes in the power of murals and public art to change lives. Nina Wright, an Oakland, California artist, also known as Girl Mobb, agrees. She once was a teenage girl creating graffiti art in her Ohio hometown. Today, she is the founder and director of the Graffiti Camp for Girls, whose mission is to “develop talent and create opportunities for young women creating public art.”

Judy believes in the power of murals and public art to change lives. Nina Wright, an Oakland, California artist, also known as Girl Mobb, agrees. She once was a teenage girl creating graffiti art in her Ohio hometown. Today, she is the founder and director of the Graffiti Camp for Girls, whose mission is to “develop talent and create opportunities for young women creating public art.”

Nina started the camp after she was asked to create a list of all murals in downtown Oakland created by women, and out of the hundreds she counted, only 20 were by female artists. The camps last a week as the girls work together to create a mural. Scholarships are available to make the camp accessible to as many girls as possible.

Her Yellow Brick Road

While art was her passion, Judy worried she couldn’t make a living as an artist, so she accepted a job teaching at her high school. Judy knew art was a powerful way to connect with students, and recruited an ethnically diverse group to create a mural for the school. Judy spent much of her personal time working with the Chicano Moratorium, a group of Mexican-American activists protesting the Vietnam War. When the school hired a new principal who disapproved of anti-war causes, Judy lost her job. She decided to take a chance on a career in art and became an apprentice at a mural workshop called La Tallera.

Celebrating the founding of SPARC (SPARC).

In 1974, Judy founded the first City of Los Angeles Mural Program, and began hiring local at-risk youth to work on murals in their neighborhoods. She was contacted by the Army Corps of Engineers, who was building the Tujunga Flood Control Channel along the Los Angeles River. The plans included walking and running paths, and the Corps asked Judy to design a mural for the area. Judy agreed, and in 1976, transitioned her mural program into a bigger non-profit, the Social and Public Art Resource Center (SPARC).

Judy long had wished that history books included more stories of women, racial and ethnic minorities, and immigrants. She now had a huge canvas on which to tell the story of California, and she named the project The Great Wall of Los Angeles. Judy gathered a team of artists and they began mapping out 5 sections, spanning from prehistoric times to the 1950s, along a half-mile stretch of the 13.5 foot high flood channel wall.

Judy with some of the Mural Makers (SPARC).

Judy recruited at-risk youth between the ages of 14-21 to work as “mural makers.” They attended art lessons, history lectures, and brainstorming sessions to help the artist decide what to feature in the mural. Once the subjects were selected, the artists drew the outlines on special paper cut into 1×2 feet squares, the designs were transferred from the paper onto the concrete and painted. Mural makers worked with the artists 4-8 hours a day in the summer, and were paid from government youth employment programs and private grants. Over 400 Mural Makers have worked on the Great Wall.

The first 1000 foot section, painted in 1976, was divided into 10 segments. Judy assigned a different artist to design each one. The first segment opens in 20,000 B.C. with animals in the Brea Tar Pits and closes in 10,000 B.C. with the Chumash Indians. The second segment revisits the Chumash in 1,000 B.C. and ends with a white hand rising from the ocean, transitioning into the third segment featuring the 18th century arrival of the Spanish explorers. The fourth segment depicts 19th century Mexican rule.

The Great Wall of California (SPARC).

The fifth segment features the 1848 Gold Rush and those who came in search of a new life, and the sixth segment depicts the racial backlash to that migration. The seventh segment highlights the role of Chinese immigrants in building the railroad, while in the eighth segment, Mexico relinquishes all claims to California and the suffrage movement begins. The final two segments that bring California into the 20th century with its growing cities and immigrants from many nations.

When the first section was finished, Judy realized the different artistic styles from 10 individual She switched gears and took over the overall design of the rest of the Great Wall. Judy and her team added another 350 feet to the mural in the summers of 1978, 1980, 1981, and 1983. Each section took at least a year of planning and discussion.

The second section of the wall covers the 1910s and 20s, with reference to World War I and Thomas Edison, who discovered electricity. The Mural Makers discovered that he was born in Mexico and adopted by a white family in the USA, and highlighted his heritage by painting the Mexican goddess Chichimeca sharing the secrets of inventors with him. The third section depicts the slide from prosperity to the Great Depression. The plight of laborers, forced sale of Indian land, and mass deportation of Mexican-Americans is brought to life. It ends with the arrival of the “Okies’ from the Dust Bowl.

The second section of the wall covers the 1910s and 20s, with reference to World War I and Thomas Edison, who discovered electricity. The Mural Makers discovered that he was born in Mexico and adopted by a white family in the USA, and highlighted his heritage by painting the Mexican goddess Chichimeca sharing the secrets of inventors with him. The third section depicts the slide from prosperity to the Great Depression. The plight of laborers, forced sale of Indian land, and mass deportation of Mexican-Americans is brought to life. It ends with the arrival of the “Okies’ from the Dust Bowl.

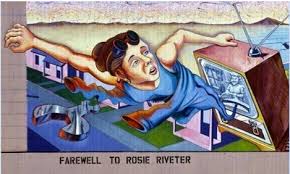

The fourth section, set in the 1940s, begins with Japanese-Americans forced into internment camps, Jewish-Americans under the shadow of Hitler, and generals and businessmen planning the war effort. There are Black women working in factories and Jewish refugees denied entry into the United States. Judy depicted the results of racial tensions created by Mexican farmworkers arriving in California to fill the jobs left open by American soldiers, who were attacked in the Zoot Suit Riots, named after distinctive attire worn by Mexican youth.

Farewell to Rosie the Riveter on The Great Wall of California (SPARC).

The fifth section, set in the 1950s, depicts working women sent back into their homes, Mexican farmworkers fighting for better working conditions. the Red Scare and Joseph McCarthy, the freeway system cutting Mexican communities in half, forced assimilation of American Indians, and the daily lives of Jewish and Asian communities. The mural ends with a celebration of Olympic champions from disadvantaged backgrounds, all of whom overcame major obstacles to succeed.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Judy’s grandparents immigrated from Mexico to Colorado where her mom was raised. The family eventually moved to California, and Judy spent the first six years of her life in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles. She lived in a Spanish speaking household with her mom, grandmother, and two aunts. Her dad was not part of their life. Judy’s mom worked in a tire factory, and her grandma was her primary caretaker.

Judy with a painting she created of her Grandma. (SPARC).

Grandma was also the neighborhood healer, and she treated all sorts of ailments with a combination of herbs, love, and prayer. Grandma talked to her plants with respect and reverence as she took clippings or transplanted them. Judy learned from her how all things were connected, and as she walked to school through the fields, she sensed that the land around her was alive. She and her friends picked plants they called “clocks” and watched their stems spin to release seed back into the earth to grow again. She remembers thinking that “I needed only to listen to the land to hear the story.”

Judy’s mom remarried when Judy was 6, and the two of them moved with her stepfather to Pacoima, a Los Angeles suburb. Not long afterward, her baby brother was born. Judy missed her old life. She had a hard time at school because she didn’t speak English and wasn’t allowed to speak Spanish. Other students made fun of her Mexican heritage. She took refuge in art class, where language didn’t matter. The art teacher encouraged her budding talent and let her sit in the corner and paint when she needed a break.

Judy at work (Judy Baca).

Judy adjusted to her new life, learned English, and welcomed a baby sister into the family. She graduated from a private Catholic high school in 1964, and continued her studies at California State University. She paid her own way through school, but was torn between her family’s wish that she live a traditional life and her desire to live independently as an artist. She got married when she was 19, graduated from college at 24, and was divorced by 25. She returned to Cal State to get her Master’s Degree in Art in 1979.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- Judy was born on September 20, 1946 in Los Angeles, CA.

- Judy is currently a Professor Emeritus in the César E. Chávez Department of Chicano/a and Central American Studies at UCLA.

- “Hitting the Wall” was a celebrated part of the Los Angeles landscape until 20 years later, when removing graffiti became a priority for the city. Graffiti artists started vandalizing murals because it was harder to remove from already painted surfaces. The government told the artists that if they didn’t remove the grafitti themselves, at their own expense, it would be painted over.

- Judy developed a coating that made it possible to remove graffiti from murals with water. She applied the coating regularly to “Hitting the Wall.” One day in early 2019, she arrived and the mural had been painted over. Judy was devastated, the public was outraged, and after an investigation, the government agreed to fund a full restoration.

- SPARC is working on plans to add sections of The Great Wall for the 1960s to 1990s, which would double its size.

- Judy has led many other public art projects, including “The World Wall: A Vision of the Future Wihtout Fear”, the Los Angeles Neighborhood Pride Mural Program, “La Memoria de Nuestra Terra” (Our Land Has Memory) at Denver International Airport, the Richmond Mural Project, and the Mural Rescue Program.

- In 2019, Judy sold one of her works, a 1979 painting titled Uprising of the Mujeres (Uprising of the Women) to the Smithsonian American Art Museum. It depicts an indigenous woman, based on Judy’s grandmother, leading workers out of the fields.

- The Judith F. Baca Arts Academy, a public school located in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles, opened in 2012.

- Judy was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2003, and a United States Artists Rockefeller Fellowship in 2015.

Want to Know More?

Baca, Judith F. “Birth of a Movement” (UCLA SPARC Nov. 9, 2001).

Olmsted, Mary. Judy Baca (Raintree 2005).

Brief Biographies. “Judith F. Baca, 1946-: Muralist, Visual Artist, Educator.”

National Park Service. Great Wall of Los Angeles.

Lambert, Molly. “Whitewashed Without Notice, Judy Baca’s Iconic Freeway Mural is Being Fully Restored” (Los Angeles Magazine Feb. 21, 2020).

SPARC. “The Great Wall History & Description.”