Culture Changer

She was the youngest of 12 children and became the first in her family to graduate from college. She pursued a career as a professor to pay her education forward, but after a humiliating encounter on a segregated Montgomery city bus, she became the architect of the first widespread and successful civil rights boycott in American history. Stand beside her on December 1, 1955 as she gets the call that Rosa Parks has been arrested and meet JoAnn Robinson…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

JoAnn’s mugshot after being arrested for her role in the bus boycott (Montgomery Country Archives).

On Thursday, December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks was arrested after she refused to give up her bus seat for a white passenger in Montgomery, Alabama. JoAnn Robinson, President of the Women’s Political Council, was one of the first to hear the news. She paused to let her initial outrage run through her body, taking time to re-live her own humiliations on Montgomery’s segregated buses. Then she sprang into action, contacting her WPC colleagues to declare that what they had been waiting for had finally happened: the perfect time for their long planned boycott of the Montgomery city bus company.

JoAnn discovered that a group of ministers from Montgomery’s Black churches planned to meet the next day. The WPC needed the churches to support the boycott to keep people encouraged, supported, and comforted. But the women feared that their plan could get bogged down in debate and negotiation if it wasn’t presented to the ministers as something already in motion for the churches to join. Time was of the essence.

JoAnn, who was an English professor at Alabama State, spent the evening typing up a flyer calling for Black citizens to boycott Montgomery’s city buses on Monday, December 5. She drove to the college to meet the chairman of the Business Department. He let her into the business office where she spent the next few hours making over 35,000 copies of the flyer. She returned home and spent the rest of the night bundling the flyers into packages for delivery.

JoAnn, who was an English professor at Alabama State, spent the evening typing up a flyer calling for Black citizens to boycott Montgomery’s city buses on Monday, December 5. She drove to the college to meet the chairman of the Business Department. He let her into the business office where she spent the next few hours making over 35,000 copies of the flyer. She returned home and spent the rest of the night bundling the flyers into packages for delivery.

As the sun rose, JoAnn returned to work to teach her 8:00am class. When she finished at 10:00am, she and two of her students set out to deliver packages of flyers to Black schools and businesses. Their goal was to widely spread word of the boycott, but to do it quietly to ensure there was no interference from authorities. JoAnn had arranged pickup times the night before so she was able to pull up, give a package to a waiting messenger, and drive away to the next stop. They needed to move quickly in order to have all deliveries done by the minsters’ meeting at 3:30pm. She was a little concerned about the outlying areas that were too hard to reach in the time she had.

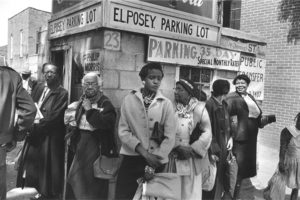

Citizens waiting for alternate transportation provided by MIA Volunteers in 1956 (Photo by Dan Weiner, copyright John Broder)

At the meeting, JoAnn shared the flyer with the more than 100 church and community leaders gathered. She informed them that the WPC had already set the boycott in motion and asked for their help with logistics and morale. The biggest challenge was providing alternative transportation, which required soliciting volunteers with cars who could spend the day driving people around. They made a map of routes where volunteer drivers and people needing rides could find each other.

After the meeting, the WPC made and distributed another flyer with the details and invited anyone interested to meet Monday night after the boycott. Meanwhile, the first flyer was making its way around the Black community. After reading the flyer, most destroyed it. However, one woman felt obligated to show it to her employer who then called the bus company, police, city government and the press. Reporters soon got ahold of the second flyer as well and published news articles in the weekend papers detailing the plans.

Empty bus during the boycott in 1956 (Photo by Dan Weiner, copyright John Broder)

Although JoAnn had been worried about the consequences if word got out too early, at this point the publicity helped more than it hurt. Now those living in remote areas were informed, and the bus company decided to hire police officers to ride behind every bus, claiming that the police presence was intended to protect riders. It ended up scaring passengers away.

JoAnn and other women from the WPC gathered on Sunday night and got very little sleep as they nervously anticipated the morning. They were concerned about the weather forecast: cold and cloudy with a chance of rain. They met on a major thoroughfare to watch the early morning buses go by. JoAnn held her breath and exhaled with relief and joy when she saw they were almost entirely empty. Instead, people walked, rode bicycles, hired a taxi if they could afford it, or got rides from the volunteers. JoAnn spent much of the day driving people to and from work.

Article from the Montgomery Advertiser Newspaper

That evening, over 6000 people attended the “next steps” meeting at Holt Baptist Church. The day had exceeded expectations. Very few rode the bus, and downtown merchants reported their receipts were down, which hurt during Christmas shopping season. The attendees unanimously agreed to continue the boycott and formed the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) to take charge. They elected one of the ministers present, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., to be MIA’s president. JoAnn turned down a public leadership role, instead choosing to serve on the MIA Executive Board.

The Power of the Wand

The WPC, with JoAnn as its leader, was the heart, soul, and engine of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, although JoAnn observed that the “boycott was not supported by a few people; it was supported by 52,000 people.” Many supporters lost their jobs or endured harassment. The “one day” boycott ended up lasting 382 days.

Even when the bus company went out of business, city leaders refused to commit to desegregation. The standoff finally ended on December 20, 1956, when the United States Supreme Court ruled that segregated seating on buses was unconstitutional. It was one of the first successful civil rights protests in the Deep South, and was the event that launched Dr. King into national recognition.

Teen girls today are continuing JoAnn’s legacy of using collective action for social change. Check out Teens Take Charge, a social movement for educational equity in New York City.

Her Yellow Brick Road

JoAnn wanted to meet people and get involved in her new hometown, so she joined Montgomery’s Women’s Political Council, which had chapters in every Black school and in businesses with 10 or more Black employees. JoAnn enjoyed her new position as an English professor at Alabama State, and started a monthly newspaper for the college with stories written by her students. The newspaper was filled with details about faculty, classes, and current events. Soon parents and the public were seeking copies because it was such a great source of information.

Not long after JoAnn arrived in Montgomery, she stepped onto an almost empty city bus and sat down in the fifth row. She didn’t realize it was a “white seat” until the bus driver verbally abused her and forced her to get off of the bus. She felt angry and humiliated and vowed then and there that she would lead an effort to desegregate the buses. JoAnn became President of WPC in 1950 and asked her fellow members to throw WPC’s weight behind such an effort. These women, most of whom were college graduates and professionals, were easily persuaded, as they also resented being treated like second class citizens.

Not long after JoAnn arrived in Montgomery, she stepped onto an almost empty city bus and sat down in the fifth row. She didn’t realize it was a “white seat” until the bus driver verbally abused her and forced her to get off of the bus. She felt angry and humiliated and vowed then and there that she would lead an effort to desegregate the buses. JoAnn became President of WPC in 1950 and asked her fellow members to throw WPC’s weight behind such an effort. These women, most of whom were college graduates and professionals, were easily persuaded, as they also resented being treated like second class citizens.

The WPC began collecting stories from Black bus passengers about the indignities they endured from segregated seating and abusive bus drivers. They heard story after story of people being arrested and fined for sitting in a “whites only” seat. The WPC spent the next few years writing letters to the bus company and filing complaints with the city. Nothing changed.

JoAnn (National Humanities Center)

The WPC needed to do something that was impossible to ignore, which meant they had to hit the bus company in the pocketbook. By 1952, JoAnn started working on a plan for a bus boycott. She figured that since 75-80% of city bus passengers were Black, a successful boycott could have an enormous financial impact. But there were massive communication and logistical challenges in convincing over 50,000 Black residents to give up one of the main, and for some only, means of transportation. WPC’s meetings centered around writing a boycott plan that could be set in motion when the timing was right.

Meanwhile, when the Supreme Court declared that segregated schools were unconstitutional in Brown vs. Board of Education, JoAnn was initially optimistic, but soon realized that the city didn’t plan to budge. She warned the mayor that there may be a bus boycott if things didn’t change, but he was willing to take his chances.

Brains, Heart & Courage

JoAnn Gibson was born in a small town in Georgia on April 17, 1912. She had 11 older brothers and sisters. Her dad died when she was young and her mom moved the family to Macon, where JoAnn attended the segregated public schools. JoAnn enjoyed writing and devoted herself to her schoolwork, which paid off when she graduated first in her class.

Nobody in her family had graduated from college, but JoAnn followed her own path to Fort Valley State College. She got her degree in education and returned to teach in Macon’s public schools for five years. She wanted to become a professor and returned to school to get her Master’s degree in English at Atlanta University. She then went to New York to do an extra year of study at Columbia University – her first experience at a school with both Black and white students.

Nobody in her family had graduated from college, but JoAnn followed her own path to Fort Valley State College. She got her degree in education and returned to teach in Macon’s public schools for five years. She wanted to become a professor and returned to school to get her Master’s degree in English at Atlanta University. She then went to New York to do an extra year of study at Columbia University – her first experience at a school with both Black and white students.

JoAnn was hired to teach English at Mary Allen College in Texas, but soon realized she wanted to be closer to home. She applied for a faculty position in the English Department at Alabama State, a historically Black college in Montgomery. She got the job and moved there in 1949. She joined the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, which soon would welcome a new minister, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- JoAnn was married to Wilbur Robinson for a few years in the 1930s. They divorced in the aftermath of their grief over losing their only child in infancy

- The Montgomery Improvement Association Resolution calling for the Montgomery Bus Boycott read: “1. All citizens of Montgomery “regardless of race, color, or creed” to refrain from riding buses owned and operated by the City Lines Bus Company “until some arrangement has been worked out between said citizens and the bus company.” 2. That every person owning or who has access to automobiles will use them in assisting other persons to get to work “without charge.” 3. That employers of persons who live a great distance from their work, “as much as possible” provide transportation for them. 4. That the Negro citizens of Montgomery are ready and willing to send a delegation to the bus company to discuss their grievances and to work out a solution for the same.

- JoAnn endured significant harassment due to her role in the boycott. She received many threatening phone calls. She was arrested two weeks in but wasn’t charged. Two months in, a police officer threw a rock through her front window. When her neighbor followed the perpetrator to the police station downtown, the Police Commissioner told him that if he wanted to live, he would go back home and keep his mouth shut. Two weeks after her broken window, she saw two police pouring something on her car in the dark. The next morning, her car had holes eaten through it from the acid they used.

- Some MIA members formed a fundraising club that sold homemade baked goods and presented the proceeds at each Monday evening meeting to a standing ovation. Other members decided to form a “rival” club and the two had a friendly weekly fundraising competition. The MIA also began receiving donations from around the world once the boycott hit the major newspapers.

- Dr. King personally asked JoAnn to write and edit a regular MIA Newsletter. As an Executive Board member, she attended every MIA meeting. She also served on the “Mayor’s Committee” which handled MIA’s negotiations with city and bus company officials. JoAnn wrote the newsletter from her meeting notes plus reports gathered from other committees. The initial edition was 4 legal size pages. By the end of the boycott each issue was 8 pages. MIA sent the newsletter to everyone on its mailing list, which eventually included thousands of people.

- As news of the boycott spread, people from all over the United States (and some from other countries) began mailing money to the MIA. Each newsletter and media story brought in thousands of dollars for MIA to pay for alternative transportation and help those who were retaliated against for supporting the boycott.

- Dr. King described JoAnn’s role in the bus boycott in his memoir Stride Toward Freedom, writing that “apparently indefatigable, she, perhaps more than any other person, was active on every level of the protest”

- JoAnn remained active in the civil rights movement in Montgomery after the boycott ended. The MIA turned its attention to desegregating train and airplane travel.

- JoAnn left Montgomery in 1960. She resigned her faculty position at Alabama State to show solidarity when the Governor of Alabama demanded that the students who participated in sit-ins at the segregated Montgomery County Courthouse lunch counter be punished by the school. She taught at Grambling State in Louisiana for a year and then moved to Los Angeles to teach there until she retired in 1976.

- JoAnn died on August 29, 1992.

Want to Know More?

Robinson, JoAnn. The Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Women Who Started It: The Memoir of JoAnn Gibson Robinson (University of Tennessee Press 1987).

Blackside, Inc. “Interview with JoAnn Robinson” (Washington University Filmed Aug. 27, 1979).

Brice, Ann. “The Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Women Who Made It Possible” (Berkeley News Podcast Feb. 11, 2020).

Staff. “JoAnn Robinson: A Heroine of the Mongtomery Bus Boycott” (National Museum of African American History & Culture).

Staff. “Robinson, JoAnn Gibson” (The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research Institute, Stanford University)

Woodhamm, Rebecca. “JoAnn Robinson” (Encyclopedia of Alabama Aug. 9, 2011)