Culture Changer

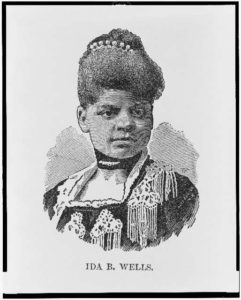

She was a teenage orphan who fought to keep her siblings together and succeeded. This fighting spirit led her to reject segregation, use the courts to enforce her civil rights, and build a career as a truth-telling journalist. She was labelled a trouble maker but didn’t let name calling or threats of violence stop her from reporting on the epidemic of lynchings of Black men in the South. When she collected all her data on lynchings into the The Red Record, she made the problem impossible to ignore. Travel back in time to 1895 and join the fight with Ida Wells Barnett…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

Ida B. Wells held a copy of her book, The Red Record, in her hands and had a sense of deep satisfaction. At about 100 pages, it was her biggest project ever. After months of research and writing, it was finally published in spring of 1895. The book was the first of its kind — it documented the cold, hard facts about the systematic lynching of Black men in the South.

Ida was angry about the lawlessness she witnessed in the South. People circumvented the legal system and took matters into their own hands. Mobs of angry white men were the police, judge and jury of actions by African Americans. The accused were allowed no defense, no witnesses, and no due process. And they were brutally punished for any or no reason.

Ida was angry about the lawlessness she witnessed in the South. People circumvented the legal system and took matters into their own hands. Mobs of angry white men were the police, judge and jury of actions by African Americans. The accused were allowed no defense, no witnesses, and no due process. And they were brutally punished for any or no reason.

At the time, many Americans considered lynchings to be rare, and very unfortunate, occurrences. They thought the practice was carried out by a small minority of militant whites in the South. Ida knew the problems were bigger than that, however. Her goal was to let the facts speak for themselves. In 25 years, over 3,000 victims were lynched by private citizens in America. And over 80% of them were African American. But those are just the lynchings that were reported. Who knows how many weren’t recorded?

In The Red Record, Ida gave a short history of lynchings and included statistics about the number of lynchings throughout the South. She went year by year, state by state, case by case. She named the victims whenever possible. She also gave the purported reason for lynching, which ranged from “Insulting Whites” to “Alleged Well Poisoning” to “A Quarrel” to “Stealing Hogs” to “Giving Information” to “Introducing Smallpox” to “No Offense/Without Cause.”

In The Red Record, Ida gave a short history of lynchings and included statistics about the number of lynchings throughout the South. She went year by year, state by state, case by case. She named the victims whenever possible. She also gave the purported reason for lynching, which ranged from “Insulting Whites” to “Alleged Well Poisoning” to “A Quarrel” to “Stealing Hogs” to “Giving Information” to “Introducing Smallpox” to “No Offense/Without Cause.”

Ida was convinced that people in the South wanted revenge for losing their way of life — they were afraid of losing power in society; they resented the freedoms that Black men achieved after the Civil War; they wanted to eliminate the competition of Black-owned businesses; they wanted to deprive Black men of participation in our democracy; and they tried to re-create white supremacy through any means possible. And they terrorized African Americans throughout the South to get their way.

Ida didn’t just educate America about the truth of lynchings. She advocated for change and urged people to act. She asked the the public to share the facts with others, condemn the lynchings, and boycott areas that were lynching “hotspots.” She also called on the federal government to hold the South accountable and pass a national lynch law. Ida was tireless in her fight for the human rights of all African Americans.

The Power of the Wand

Ida was a pioneer of investigative journalism. She was methodical in her work — gathering information and letting the facts speak for themselves. Over the years, Ida published four books, gave over 20 speeches, and wrote hundreds of newspaper articles.

Many women have built upon Ida’s legacy over the years. Between 1900-1970, the number of women in journalism nearly doubled. Today, organizations such as WriteGirl are helping teen girls develop the skills required to succeed as a writer.

Across the country, student reporters for school newspapers have effected real change in their communities. For example, in 2017, the student reporters at Pittsburgh High School in Kansas did some fact-checking on their new principal and saw some red flags. Likewise, a student reporter at Amherst-Pelham Regional High in Massachusetts uncovered a plan to have the auditorium seats re-upholstered by unpaid prison laborers in 2019.

Her Yellow Brick Road

Ida’s journalism career began in her hometown of Memphis. She had finally found her calling. In 1889, Ida started to write for the Free Speech newspaper. She eventually became a co-owner and served as the newspaper’s editor (Ida wrote much of the content herself).

Then, a horrific event changed the course of Ida’s life. Three black men were lynched in 1892, including one of her friends. It all started when a Black boy won a game of marbles. And escalated from there. Eventually, a group of white men kidnapped three Black men, drove one mile past the Memphis city limits, and shot them in cold blood. No one was ever arrested for the crime.

The lynchings rocked the Memphis community and propelled Ida to action. She was completely outraged at the event. She spoke at protests and demanded justice in the Free Speech. She was convinced the police knew the identities of the killers but refused to act. And she encouraged African Americans to leave Memphis. Before long, her stories were reproduced by newspapers around the country. She aired the South’s dirty laundry before the nation.

Ida’s actions angered the white population in Memphis — they looted the Free Speech newspaper office and burned it down. Luckily, Ida was out of town. It was clear that Ida’s life was in danger if she returned to Memphis. The mob wanted to lynch her too. So she moved to New York City.

Ida continued her campaign from the North, meticulously researching the lynchings that took place throughout the South. She began to publish her work in the New York Age, a prominent Black newspaper in Brooklyn. Her articles were picked up by other Black newspapers across America. She finally had a national voice. And she was going to use it.

Ida started to give anti-lynching lectures. She was disappointed by the lukewarm reception by the white Americans in her audiences, however. She became convinced that no Black woman would ever convince a white audience they were wrong, even in the North. Eventually she took her case abroad and gave lectures in England. Her theory was that the white population in England held more influence with their counterparts in America than she ever would.

Ida was known as “Princess of the Press.” Ida had a talent for expressing in words the outrage that African Americans felt about the injustices in society. But she was a controversial figure — sometimes she was too abrasive. As a result, she didn’t have the support of other Black leaders. Ida fought for her ideals, however, and never gave up. Her anger propelled her forward. She learned from defeat, kept up hope, and looked towards the future.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Ida grew up as the oldest of eight children in Mississippi. The Civil War had just ended and her parents had high hopes for the future of their children. She was a voracious reader throughout her life and enrolled in school at an early age.

Unfortunately, Ida became an orphan when she was 16 years old. Her parents both died from yellow fever. So she stepped in as the head of the household and took care of her siblings. She worked hard to keep the family together and refused to let them be split up in foster homes. Ida needed an income, so she she moved to Memphis and became a school teacher.

Ida refused to subject herself to the public humiliation of segregation, especially when she traveled by train. So she bought first class tickets for the Ladies Car, then boarded and hoped for the best (like many other Black women at the time). Sometimes it worked out and sometimes it didn’t. Ida was forcefully removed from the Ladies Car twice and sued the railroad companies both times. She won and was awarded a total of $700 from both lawsuits. She developed a reputation as a “trouble-maker,” however, as a result of the lawsuits.

Before long, Ida began to write about her experiences in the local paper. She lost her job as a teacher after she wrote about the poor conditions in schools for Black students. But she didn’t care. The story had to be told.

Ida she found her calling. She became a journalist and focused on issues she saw in society, writing under the pen name “Iola.” Her articles were so popular that they were reprinted throughout America.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- Ida was born in Holly Springs, Mississippi on July 16, 1862 (she was born as a slave). Ida grew up as the oldest of eight children Her mother was very religious and her father was involved in local politics. They both died of yellow fever in 1878.

- Ida attended Shaw University (now Rust College) for a few years, but never graduated. She was a school teacher before becoming a journalist. Ida loved the theater and organized a drama club. She also loved to travel and was constantly trying to improve herself.

- Ida was involved in a boycott of the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893, in retaliation for the black community being excluded from the event. Ida co-wrote a brochure called “The Reason Why: The Colored American is not in the World’s Columbian Exposition.”

- Ida married Ferdinand Barnett in 1895. They had four children together — Charles, Herman, Ida, and Alfreda. In addition, Barnett had two children from a previous marriage.

- Ferdinand was also a journalist and founded a black newspaper in Chicago called the Conservator. Ida became editor of the newspaper after they married.

- Ida was involved in founding the National Association for Colored Women in 1896. After the World’s Fair ended, her civil rights work continued in Chicago through a newly formed organization — the Ida Wells Club. The Club established the first black kindergarten in Chicago.

- Ida was part of a group that met with President McKinley in 1898, to request that he take federal action to stop lynchings.

- Ida was also involved in the beginnings of the NAACP. She was on its executive committee shortly after it was organized (but wasn’t part of the original Committee of 40).

- In 1913, Ida worked full time as Chicago’s first black adult probation officer.

- Ida ran for the Illinois State Senate in 1930, but lost.

- Ida was one of the first Black women to write her autobiography.

- Ida died on March 25, 1931 from kidney disease at 68 years old. She remained a controversial figure to her death, and was excluded by other leaders of the Black community.

- The Ida B Wells Commemorative Art Committee has raised $300,000 for the construction of a memorial in the Bronzeville neighborhood of Chicago. When it’s completed, the monument will be donated to Chicago’s Public Art Collection.

- She was awarded a Pulitzer Prize for investigative journalism in 2020, 90 years after her death.

Want to Know More?

Edwards, Linda Murray. To Keep the Waters Troubled: The Life of Ida B Wells. Oxford University Press, 1981.

Giddens, Paula. Ida, A Sword Among Lions. New York: Amistad, 2008.

Wells, Ida B. Ed. Alfred Duster. Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1970.

Wells, Ida, ed. Douglass, Frederick; Penn, Irvine; Barnett, Ferdinand. “The Reason Why: The Colored American is not in the World’s Columbian Exposition.” (accessed at https://digital.library.upenn.edu/women/wells/exposition/exposition.html)

Wells, Ida B. “The Red Record.” 1895 (accessed at https://www.gutenberg.org/files/14977/14977-h/14977-h.htm)

Wells, Ida B. “Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in all its Phases.” 1892 (accessed at https://www.gutenberg.org/files/14975/14975-h/14975-h.htm)