Passionate Patriot

Her culinary creativity on a rainy day in a World War I army camp led to the doughnut being one of the most beloved snacks in the United States today. Travel back in time to a Salvation Army canteen hut in 1917 and meet Helen Purviance…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

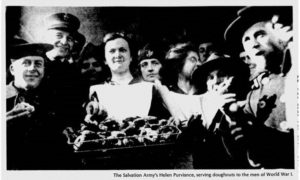

Helen Purviance dodged cold raindrops as she trudged through the mud to the army commissary on October 19, 1917. Her friend Margaret Sheldon was waiting for her back at the Salvation Army canteen hut where they both worked. Helen and Margaret had arrived at an army camp in Eastern France about 6 weeks earlier as part of the first Salvation Army contingent of the Great War.

Helen in uniform (Territorial History Museum)

Their mission was to provide moral and emotional support to the American soldiers who had recently deployed to fight. They hadn’t been trained specifically for wartime, so they offered the same comforts they provided to the struggling at home, including music, religious devotions, and sweet treats like fudge and hot chocolate.

It had been raining for 36 straight days. Helen had grown increasingly worried about the health of the soldiers, as they were vulnerable to illness and infections from spending so much time in wet and cold battlefield trenches. Helen wanted to feed them something that had more nutrition and substance than fudge, but was still sweet and comforting. That desire sparked her trip to the commissary, where she grabbed all the available ingredients she could find to combine with the eggs the local villagers donated daily: lard, flour, sugar, baking powder, salt, and canned condensed milk.

Helen making doughnuts (Salvation Army)

As Helen walked back to the canteen hut, she calculated the different foods she could make with her limited ingredients. She initially considered pancakes, but she didn’t have forks, plates, butter or syrup. The soldiers needed something they could grab and eat easily with their hands. Helen decided to try to make doughnuts.

Helen and Margaret had few traditional cooking utensils handy, so they had to improvise. They used a wine bottle to roll dough into long ropes, then braided the ropes together and cut them into sections. Helen heated the lard in a skillet pan on the single burner of their pot-bellied wood burning stove. The women took turns frying the doughnuts and keeping the fire stoked. The stove was so small that they women were on their knees when frying the doughnuts, seven at a time.

Helen had hung a blanket in front of the stove because she wanted to surprise the soldiers. But the delicious smell of freshly fried doughnuts gave her away. The soldiers lined up, in the rain, for their chance to enjoy a special treat. “And you should have seen their faces,” she recalled. The first soldier in line reportedly said “If this is war let it continue!”

Helen had hung a blanket in front of the stove because she wanted to surprise the soldiers. But the delicious smell of freshly fried doughnuts gave her away. The soldiers lined up, in the rain, for their chance to enjoy a special treat. “And you should have seen their faces,” she recalled. The first soldier in line reportedly said “If this is war let it continue!”

Rolling and braiding the dough was slow, so they were only able make 150 doughnuts that first day. Helen and Margaret spent the next few days experimenting and determined that a ring shape was easiest to make and distribute. Helen used shell casings and empty condensed milk cans with a narrow tube of camphor ice attached in the middle to quickly cut dough into rings. She eventually found a blacksmith who made a cutter from a milk can, shaving soap tube, and block of wood. In order to fry more doughnuts at a time, the women used any durable metal item they could find that could hold hot lard, including discarded soldiers’ helmets and galvanized trash cans.

Helen and Margaret were soon making 2500-8000 doughnuts a day for the soldiers and earned the nickname “Doughnut Lassies.” Salvation Army volunteers in other camps began making doughnuts for their soldiers too. Rolling pins and ring cutters became essential supplies shipped from home. The doughnut’s impact on army morale was huge. The Syracuse Herald observed that “by the time a lad with a longing for home has absorbed the three bites- that’s all there are in a properly constructed doughnut – he begins to feel that perhaps somebody loves him after all. He can vision home.”

Helen and Margaret were soon making 2500-8000 doughnuts a day for the soldiers and earned the nickname “Doughnut Lassies.” Salvation Army volunteers in other camps began making doughnuts for their soldiers too. Rolling pins and ring cutters became essential supplies shipped from home. The doughnut’s impact on army morale was huge. The Syracuse Herald observed that “by the time a lad with a longing for home has absorbed the three bites- that’s all there are in a properly constructed doughnut – he begins to feel that perhaps somebody loves him after all. He can vision home.”

The Power of the Wand

Doughnuts were not very popular in the United States until after World War I. When the soldiers got home, they craved the treat that had given them so much comfort. The military created a “how-to booklet” to guide veterans who wanted to open doughnut shops.

The Salvation Army in Chicago created National Doughnut Day in 1938 to honor the Doughnut Lassies. It is celebrated on the first Friday of June each year. You can carry on Helen’s legacy by making her doughnut recipe at home.

Helen & Margaret’s Doughnut Recipe

WW1 Poster (saved by Salvation Army)

Ingredients:

5 C flour

2 C sugar

5 tsp. baking powder

1 ‘saltspoon’ salt (1/4 tsp.)

2 eggs

1 3/4 C milk

1 tub lard

Directions:Combine all ingredients (except for lard) to make dough. (If you want to add cinnamon or vanilla to the dough, do so. The Doughnut Lassies did when it was available).

Thoroughly knead dough, roll smooth, and cut into rings that are less than 1/4 inch thick. (When finding items to cut out doughnut circles, be creative. Doughnut Lassies used whatever they could find, from baking powder cans to coffee percolator tubes.)

Drop the rings into the lard, making sure the fat is hot enough to brown the doughnuts gradually. Turn the doughnuts slowly several times.

When browned, remove doughnuts and allow excess fat to drip off.

Dust with powdered sugar. Let cool and enjoy.

Her Yellow Brick Road

World War I began in 1914. The United States tried to remain neutral, but once the Germans started blocking Atlantic Ocean shipping lanes and attacking American ships, that was no longer possible. The United States declared war in April 1917, soldiers started getting drafted in June, and there was a big push to rally the country and get people enthusiastic about going to war. Morale building was a critical part of this plan.

Helen in France (Salvation Army)

The Salvation Army had been ministering to the poor and disadvantaged in the United States for more than 50 years. Its organization mirrored the military, with ranks from Private (new volunteer) to Generals (highest ranking officer). With the declaration of war, the Salvation Army swung into action, seeking volunteers to follow the soldiers to Europe to provide humanitarian relief. Helen volunteered to be among the first group to go, and she left for France on August 10, 1917. Of the 11 officers in that group, 4 were single women.

Helen and Margaret ended up in an army camp just a few miles from the front line trenches outside the village of Montiers-sur-Saulx in Eastern France where the First Division Ammunition Train was stationed. They set up a canteen hut, restroom, and hostel near camp. They provided comfort for homesick and scared soldiers, including reading to them, mending their uniforms, and supplying stationery and letter writing help. They hosted concerts and Christian and Jewish religious services and prepared sweet treats and hot drinks to boost their spirits. The soldiers took turns rotating from the camp into the battlefield trenches, where they lived for up to 30 days at a time, often in standing water. The horrible conditions took their toll, and they were in great need of peace and comfort when they returned to camp.

Conditions at camp were better than the trenches, but still dangerous. Helen and Margaret slept in tents and battled the cold and the bugs. They were within firing range of the Germans, and while most bomb and gas attacks were aimed at the trenches, they still had to be ready for a longer range attack. Helen had been issued a gas mask, helmet, and gun. She took target practice to learn how to defend herself if necessary. They heard machine gun fire constantly, and one bomb fell within 10 yards of the canteen hut but didn’t explode. If it had, they all likely would have been killed. Although women were banned not just from combat, but from being in the military altogether, they still were risking their lives to be at the front.

Conditions at camp were better than the trenches, but still dangerous. Helen and Margaret slept in tents and battled the cold and the bugs. They were within firing range of the Germans, and while most bomb and gas attacks were aimed at the trenches, they still had to be ready for a longer range attack. Helen had been issued a gas mask, helmet, and gun. She took target practice to learn how to defend herself if necessary. They heard machine gun fire constantly, and one bomb fell within 10 yards of the canteen hut but didn’t explode. If it had, they all likely would have been killed. Although women were banned not just from combat, but from being in the military altogether, they still were risking their lives to be at the front.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Helen grew up in a small town in Indiana. Her dad worked at the local hardware store while her mom stayed home to take care of Helen and her four siblings. Helen followed her three older siblings to boarding school when she was 11. She spent the next six years there, coming home for winter break and summer vacations.

A view of the doughnut line (Salvation Army)

After graduation, Helen returned home and joined the Huntingdon Salvation Army Corps. Inspired by the difference she could make, she moved to New York City to attend Salvation Army officer training college. When she was 19, she was commissioned as a lieutenant and spent the next five years serving short tours of duty in different New York towns. Helen’s natural interest in people made her an effective advocate for those in need. She built strong relationships with the political and business leaders in the communities she served, knowing that cultivating their support was critical to her mission.

Helen’s supervising officers noticed her talent for creative problem solving and asked her to assume leadership at the struggling Oswego, NY Salvation Army Corps. Helen instituted needed structure and leveraged her relationship building skills into a successful capital campaign for a new building. In 1914, she was commissioned as a Captain, and then promoted to Ensign three years later, just before she left for France. She remained very connected to her hometown and visited her family whenever her schedule allowed.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- Helen was born on February 16, 1889 in Huntingdon, Indiana.

- Helen and Margaret moved camps with the Salvation Army 10 times from September 1917 to April 1918. In January 1918, they moved close to the front lines and their duties expanded to treating wounded soldiers. Both women stayed in France until end of the war that November.

- By end of the war, Helen had made over one million doughnuts and came home with a chronic pain she called “doughnut wrist”

- Helen was recognized by General John J. Pershing, American Expeditionary Force Commander, for her service and valor under fire.

- Helen returned to the Oswego Salvation Army Post after the war. She became a minor celebrity after the war as one of the original Doughnut Lassies. She was a regular invited speaker at church services and meetings.

- Helen and her brother Paul established the Huntington, Indiana Salvation Army Post in 1919.

- Helen began teaching at Salvation Army College of Officer Training in New York in 1924 and was appointed Dean of Women there in 1936.

- Helen retired from the Salvation Army in 1949 with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel.

- Helen’s hometown has embraced her legacy in various ways. The mayor presented her with a gold-plated doughnut in 1965. For the WWI Centennial celebration in 2018, they celebrated Helen Purviance Day where they recreated a Salvation Army canteen and made the doughnuts from Helen’s recipe.

- Helen died on February 26, 1984 at the age of 95. She is buried in Mt. Hope Cemetery in her hometown.

Want to Know More?

Edge, John T. Doughnuts: An American Passion (Reed Elsivier 2006).

Gavine, Lettie. American Women in World War I (University Press of Colorado 1997).

Boissoneault, Lorraine. “Doughnut Girls: The Women Who Fried Doughnets and Dodged Bombs on the Front Lines of WWI” (Smithsonian Magazine, April 12, 2017).

Croyle, Johnathan. “Love doughnuts? Read about Central New York’s Role in Popularizing the Treat” (Syracuse.com Feb. 23, 2019).

McBride, Connor. “Helen J. Purviance: The First Salvation Army “Doughnut Girl” (The United States World War I Centennial Commission).

Staff. “Huntingdon’s own WWI Doughnut Girl to be Feted Saturday” (Huntingdon County Tab April 9, 2018).

Yagi Jr., George. “Doughboys and Doughnut Girls – How the Salvation Army’s WWI Women Volunteers Made History, One Tasty Treat at a Time” (Military History Now May 31, 2018).