Super Scientist

The loss of her grandfather when she was a teenager inspired her dream to find a cure for cancer. Her love for learning and willingness to take risks overcame the roadblocks put in place for women in science in the 1930s and 1940s. She gave up a Ph.D. program because the work she was doing in her day job at a pharmaceutical laboratory was inching closer and closer to a breakthrough. Travel back in time to 1950 and witness medical history being made with Gertrude Elion…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

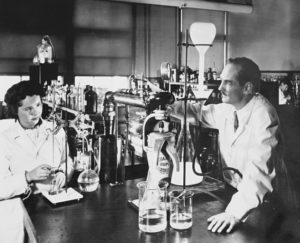

Gertrude Elion had been waiting for this day for a very long time. Trudy, as friends and family called her, had been determined to find a cure for cancer since she lost her beloved grandfather when she was only 15 years old. She became a chemist in pursuit of that goal and had been working as an assistant in a pharmaceutical lab run by Dr. George Hitchings for about 6 years. Now in 1950, at age 32, she knew they were on the verge of a major breakthrough.

George & Trudy in the lab in 1948.

George encouraged Trudy’s creativity. They both liked to think outside the box and had decided to experiment with a new approach to drug development. They wanted to move away from the trial and error method, which essentially required scientists to randomly test hundreds of things to find the ones that worked. Trudy and George believed there was a more rational way. If they understood how the various cells worked first, they could test chemical compounds that specifically target their structure and function. If it worked, they could design better and safer drugs more efficiently.

They were intrigued by the introduction of sulfa drugs to treat pneumonia, bronchitis, malaria, and other bacterial diseases. Sulfa worked not by killing bacteria themselves, but by interfering with bacterial multiplication and growth. George and Trudy theorized that there must be other substances that could block growth of viruses and cancer cells.

George’s lab centered around nucleic acids, which are the information carrying molecules in cells. The two most well-known nucleic acids are DNA and RNA, which in turn are made of pairs of purines and pyrimidines. George assigned Trudy to research purines. Trudy liked to think of herself as a detective solving mysteries – her job was to decipher why a cell behaved the way it did. She observed that bacterial cells needed purines to make DNA, which in turn was needed in order for the cell to replicate.

George’s lab centered around nucleic acids, which are the information carrying molecules in cells. The two most well-known nucleic acids are DNA and RNA, which in turn are made of pairs of purines and pyrimidines. George assigned Trudy to research purines. Trudy liked to think of herself as a detective solving mysteries – her job was to decipher why a cell behaved the way it did. She observed that bacterial cells needed purines to make DNA, which in turn was needed in order for the cell to replicate.

This discovery led to more questions: what would happen if they blocked the purines from triggering the metabolic process of the cell. Would it prevent the bacteria from reproducing? So they began studying the differences in DNA and RNA metabolism between single cell organisms, normal human cells, and human cells infected by bacteria, viruses, and cancer. They created and tested different combinations of chemicals, searching for one that would prevent abnormal cells from replicating. They needed to find something that the metabolic enzymes would attach to before they reached the natural purines and triggered DNA growth. This process had taken a few years, and Trudy had already published 225 papers on her findings leading up to this point.

This time, they were experimenting with a drug combination of two purines, diaminopurine and thioguanine, in a leukemia cell. And it worked! The enzymes attached to the drug instead of the cell, blocking DNA production and stopping replication.

Wellcome Burroughs Special Nobel Prize Issue featuring George & Trudy

This was a medical miracle – many forms of leukemia went from a death sentence to something treatable. Remission was now a viable hope for many patients. But there was still much work to be done, as these new chemotherapy treatments had many terrible side effects. Trudy got to work on trying to alter the purine combinations to be more gentle on the body while not losing effectiveness against cancer. She tested more than 100 alternatives, substituting one element for another, before creating one called 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP).

Trudy was cautiously optimistic about 6-MP as it went through testing. Once it was ready to try on children suffering from leukemia, Trudy was nervous but confident. And her hopes were realized – children treated with 6-MP went into complete remission. But Trudy wanted to find a cure for them, so went back into the lab to do more work. And her work led to another drug, called thioguanine, which also became part of the leukemia treatment plan. Trudy’s drugs laid the foundation for a treatment that still, today, cures 80% of childhood leukemia patients.

The Power of the Wand

Trudy and George, along with scientist James Whyte Black, won the 1988 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine for their pioneering approach to drug development. Under their rational drug design method, scientists study the structure and function of cells in order to decide what to test. Scientists identify a specific enzyme or receptor that they want to target. They then work to find drugs that attach to the targets and direct the cell to either heal itself or stop reproducing. Trudy kept a file of letters from patients who wrote to tell her how her discoveries had helped them heal. She loved hearing their stories and said that these letters were “a reward greater than the Nobel Prize.”

Researchers all over the world use Trudy’s approach to make medical advances. One of them is Duke University MD/PhD student Shree Bose. When she was 17, Shree was the Grand Prize Winner in the first ever Google Global Science Fair in 2011. Shree now spends much of her time in the lab doing cancer research – her focus is understanding metabolic changes that cause cancer to grow and spread. Learn more about her work at www.shreebose.com.

Her Yellow Brick Road

Trudy when she was a Hunter College student. (Gertrude B. Elion Foundation)

Trudy left college with a degree in chemistry and a drive to use it. But there weren’t many labs with open positions, and those that were hiring did not want women. Trudy did find a position teaching biochemistry at the New York Hospital School of Nursing. But the class was only offered one quarter a year, so once it was over, she was looking at nine months with no work.

Trudy then met a chemist who needed a lab assistant, but couldn’t afford one. She decided to work for him anyway, gambling that the experience gained would be worth it. Eventually, her boss was able to pay her a small salary, but more importantly, as she had hoped, her work at the lab was a springboard to bigger things. She saved enough money for one year of graduate school, applied to NYU, was accepted, and started there in Fall 1939. She was the only woman in her class.

After her first year, she needed to find a way to work and finish her degree. Fortunately, by this point she just needed to find time to be in the lab doing research for her Master’s thesis. She took a quick secretarial class so she could work temp jobs. She also earned money as a substitute science teacher at some local high schools. For two years, she taught during the day and spent her nights and weekends in the lab. She barely had a moment to breathe, but earned her Master of Science degree in chemistry in 1941.

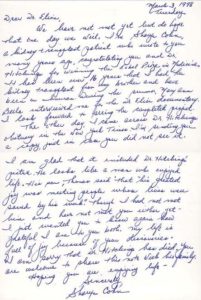

Letter written to Trudy by a kidney transplant patient to tell her “my life is full of joy because of you.”

Trudy got her degree just as there was a growing need for scientists to aid the World War II effort. As men left their positions to join the military, jobs in industrial labs opened up. She was hire to do quality control for a major food company. She became proficient at using lab instruments, but after a few years grew bored running the same tests over and over again.

Trudy sent her resume to an employment agency, and thought she had her big break when she was assigned to a Johnson & Johnson lab in New Jersey, but the lab shut down after only 6 months. The good news was that she now had research experience, which gave her credibility. She went back on the market and got many offers from other labs. While choosing between them, Trudy did what she always did– she took the position that could teach her the most. She took a position as an assistant to Dr. George Hitchings, a biochemist running a research lab for a pharmaceutical company called Burroughs Welcome.

Trudy thrived in his lab, as he was the kind of boss who rewarded hard work with greater responsibility. He also encouraged her to not feel limited by her chemistry degree, but to take the opportunity to learn about the other sciences that relate to medical research, like biology, pharmacology, and immunology.

He also inspired Trudy to pursue her own doctorate degree. As with her Master’s, Trudy had both a day job and then academic responsibilities on nights and weekends at the Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute. But it proved impossible to do part time – her Ph.D. research needed more attention, and the commute between Brooklyn and New Jersey started to wear on her.

He also inspired Trudy to pursue her own doctorate degree. As with her Master’s, Trudy had both a day job and then academic responsibilities on nights and weekends at the Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute. But it proved impossible to do part time – her Ph.D. research needed more attention, and the commute between Brooklyn and New Jersey started to wear on her.

After a few years, BPI told Trudy that she needed to commit to the doctorate program full-time, which would mean quitting her job with Dr. Hitchings. Trudy was torn. Becoming Dr. Elion was a dream, but the work she was doing in Hitchings’ lab was a reality she didn’t want to give up. So she stayed.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Trudy was raised in New York City by her parents, both of whom had come to the United States as children. Her father’s family immigrated from Lithuania when he was 12, her mom’s from western Russia (later Poland) when she was 14.

Trudy at age 5. She loved to spend time with her grandpa.

Her dad was a dentist. They lived in an apartment in Manhattan that was divided between their living space and his dental office. When Trudy was 6, her little brother was born, and the family needed more room. They moved to the Bronx, where there was plenty of open space, parks, and the Bronx Zoo. The kids walked to their local public school. Trudy absolutely loved learning and when asked what her favorite subject was, her answer was “all of them!”

Trudy skipped four grades and graduated high school in 1933, when she was only 15. She wanted to go to college, but her opportunities were limited. Her family was nearly bankrupt, having suffered big losses in the stock market crash of 1929. They were also grieving the loss of Trudy’s beloved grandfather, who had died after a slow and painful battle with stomach cancer. Her only chance was admission to a local all-women’s school, Hunter College, that offered free tuition to students with excellent academics. Trudy applied, was accepted, and started there in the fall.

When it came time to decide on a major, Trudy decided on chemistry, in the hopes that she would be able to be part of the fight against the cancer that claimed her grandpa. She devoted herself to her studies, and graduated summa cum laude in 1937. Trudy wanted to continue studying chemistry in graduate school, but couldn’t afford the tuition. She applied for 15 different research fellowships, which would have paid for her studies, around the country. She was rejected by all 15. She had to come up with a Plan B.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- Trudy was born in New York City on January 23, 1918. It was so cold that night the water pipes in her parents’ apartment froze and burst.

- Trudy and George spent much of the 1960s doing research to find drugs that would inhibit the growth of bacterial cells to treat infectious diseases. They developed treatments for illnesses like malaria, meningitis, septicemia, as well as urinary and respiratory bacterial infections.

- Trudy’s research also advanced treatment of organ transplant recipients. She discovered a drug named azathioprine, which helped patient’s immune systems accept their new organ.

- Trudy was appointed Head of the Department of Experimental Therapy at Burroughs Welcome in 1967. It was a multi-disciplinary lab where scientists doing work in chemistry, enzymology, pharmacology, immunology and virology, and tissue culture coordinated efforts to develop new drugs. A primary focus was looking for drugs to stop viral replication. They created anti-viral treatments for herpes, and some of the scientists who worked in Trudy’s lab later went on the develop the anti-viral AIDS drug, AZT.

- Trudy became a well-known cancer researcher. At the National Cancer Institute, she served on study sections, advisory committees, the Board of Scientific Counselors for the Division of Cancer Treatment, and the National Cancer Advisory Board. She was on program committees and the Board of Directors of the American Association for Cancer Research, and in 1983-84 was its President. She also served on Advisory Committees for the American Cancer Society and the Leukemia Society of America.

- Trudy also created a name for herself in tropical disease research, serving on committees for the Tropical Disease Research division of the World Health Organization, and as Chairman of the Steering Committee on the Chemotherapy of Malaria.

- Trudy was a member of several scientific organizations, including the American Chemical Society, the Royal Society of Chemistry, the Transplantation Society, the American Society of Biological Chemists, the American Society of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, the American Association for Cancer Research, the American Society of Hematology, the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the American Association of Pharmaceutical Scientists, and New York Academy of Sciences.

- In 1968, Trudy became one of the only women to ever win the American Chemical Society’s Garvan Medal.

- After Trudy retired from her leadership role at Burroughs Welcome, she stayed on as a Scientist Emeritus and Consultant. She also started teaching at Duke University as a Research Professor of Medicine and Pharmacology. As part of her duties there, she mentored one third-year medical student each year in tumor biochemistry and pharmacology research.

- Trudy finally got a Ph.D. when she was awarded honorary doctorates from George Washington University, Brown University, and the University of Michigan.

- Trudy loved her work so much that she had to make a conscious effort to step out of the lab and experience life. She loved travel and photography, and combined those two passions into trips around the world. She also was a subscriber to the Metropolitan Opera for over 40 years.

- Trudy never married. She was engaged once, but her fiancé died of inflammation of his heart lining before they were wed. She was a very involved aunt to her niece and three nephews.

- Trudy died on February 21, 1999. She was 81.

Want to Know More?

Staff. “Gertrude B. Elion – Biographical” (Nobel Prize Outreach 1988).

Staff. “Women Who Changed Science: Gertrude Elion” (Nobel Prize Outreach 1988).

Staff. “Women Scientists: Gertrude Elion (1918-1999)” (ACS 1999).

Staff. “Historical Profile: George Hitchings & Gertrude Elion” (Science History Institute Dec. 5, 2017).