Culture Changer

She was a girl who loved to read who grew into a woman who loved to write. Her poems, short stories, and novels captured the passion and angst of an era where your freedom depended on your identity. Step into a publishing house in Philadelphia in 1892 and meet Frances Watkins Harper…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

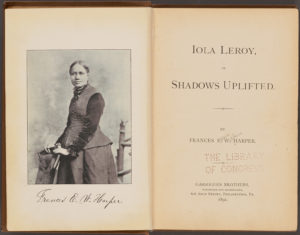

It wasn’t the first time Frances Watkins Harper had seen her work in print. She had published books of poetry and serialized novels in magazines. Her suffrage and civil rights speeches had been featured in many newspapers and pamphlets.

But holding the bound edition of her novel Iola Leroy; or, Shadows Uplifted was different. The number of published Black women novelists in the United States could be counted on one hand. It was 1892, and Frances was acutely aware of the growing resentment of the progress Black citizens had made since the end of the Civil War. Efforts to prevent Black men from voting and to enforce segregation were increasing, along with lynchings and other violence.

But holding the bound edition of her novel Iola Leroy; or, Shadows Uplifted was different. The number of published Black women novelists in the United States could be counted on one hand. It was 1892, and Frances was acutely aware of the growing resentment of the progress Black citizens had made since the end of the Civil War. Efforts to prevent Black men from voting and to enforce segregation were increasing, along with lynchings and other violence.

Frances was 67 and had spent much of her life thinking, talking, and writing about how identity can define, expand, and limit human existence. Frances knew from her own lived experience that identity was important, but not determinative. There were Black Americans whose families had been enslaved, and those whose ancestors had been free. Some now lived lives of luxury and others struggled for every penny. Likewise, not all women were pro-suffrage, and those who were often couldn’t agree on how best to achieve it. Some people chose political activism and others lived their lives quietly.

Frances decided to write a novel about identity. She was inspired by people she had known who wrestled with the question of what it means to be white, and what it means to be Black. She knew many light skinned people with Black ancestry who had faced the choice of whether to “pass” as white. Before and during the war, being white was protection against being enslaved. After the war, being white allowed you to walk through doors still closed to Black people.

Frances decided to write a novel about identity. She was inspired by people she had known who wrestled with the question of what it means to be white, and what it means to be Black. She knew many light skinned people with Black ancestry who had faced the choice of whether to “pass” as white. Before and during the war, being white was protection against being enslaved. After the war, being white allowed you to walk through doors still closed to Black people.

Frances’ novel tells the story of Iola Leroy, from her antebellum childhood in Louisiana through the Civil War and Reconstruction. Iola doesn’t know that her mom is a freed slave of mixed race. Iola and her siblings are raised as white children. While Iola is at boarding school in the North, her dad dies and his family, who disapproved of his marriage, arranges for his family to be enslaved. When Iola returns home, she is told she is a Black woman and a slave, and sold away from her mother to someone in North Carolina. She is freed when the Union Army arrives in town. She becomes an Army nurse and vows to find her family. When Iola meets a white doctor who falls in love with her, she must choose whether to live as a white woman with all of the advantages that accompany it, or acknowledge her Black heritage and be reunited with her family.

Throughout the story, Frances has her characters debate the issues of the time. They discuss whether the best approach to racial progress is to build a Black culture and economy or try to integrate white spaces; whether women should have the right to vote; and whether alcohol should be prohibited. Race, class, and gender all intertwine in her characters’ fates, but isn’t determinative. Individual agency and choice play a role in their lives as well.

Frances wrote in Iola Leroy’s afterword that she wrote the novel to challenge her readers and awaken their sense of justice for “those whom the fortunes of war threw, homeless, ignorant and poor, upon the threshold of a new era.” She hoped the story would inspire people to “embrace every opportunity, develop every faculty, and use every power God has given them to rise in the scale of character and condition, and to add their quota of good citizenship to the best welfare of the nation.”

Frances wrote in Iola Leroy’s afterword that she wrote the novel to challenge her readers and awaken their sense of justice for “those whom the fortunes of war threw, homeless, ignorant and poor, upon the threshold of a new era.” She hoped the story would inspire people to “embrace every opportunity, develop every faculty, and use every power God has given them to rise in the scale of character and condition, and to add their quota of good citizenship to the best welfare of the nation.”

The Power of the Wand

Iola Henry was a success. It was reprinted four times in four years. But because it was an emotional story focused on family relationships, it was considered a “women’s novel”, and not important enough to keep in print long term. Many American novels authored by Black women in the late 19th and early 20th century were similarly treated. Women scholars rediscovered these novels in the 1970s. Iola Leroy was republished in 1971 and is still in print today.

Frances wrote about the interaction between identity and choice, and how both intertwine to shape a life. These themes are explored in two recent young adult novels written by Black women authors: Genesis Begins Again by Alicia D. Williams and You Should See Me in a Crown by Leah Johnson. In very different ways, both novels center around teenage girls wrestling with the questions of who they are, and who they want to be.

Her Yellow Brick Road

The Fugitive Slave Act was passed by Congress in 1850, allowing “slave catchers” to track down and return slaves who had escaped to the North, even if the state where they lived recognized them as free. The same year, Frances accepted a position to teach domestic science at the Union Seminary in Wilberforce, Ohio.

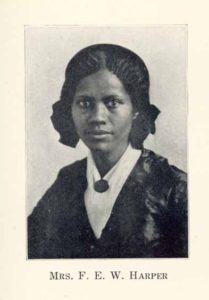

Frances as a young woman (Hallie G. Brown).

Union was one of the only colleges in the country where free Black people could study. No woman had taught there before, and many of the staff and students vigorously opposed Frances joining the faculty. But she had the support of the school’s principal and stayed for 2 years. She then moved to York, Pennsylvania to teach, boarded in a house that doubled as an Underground Railroad Station, and helped care for those who stopped to rest on their journey to freedom.

Frances began using her poetry to express her grief and anger over slavery. Her poems were a compelling and accessible vehicle for readers to truly comprehend its horrors. One of her more well-known poems, “The Slave Auction” describes “the sale began-young girls were there, Defenseless in their wretchedness, Whose stifled sobs of deep despair Revealed their anguish and distress.” Frances also authored the popular “Aunt Chloe” series of popular poems, written from the first person point of view of a Black woman.

By 1854, Frances’ home state of Maryland had passed laws allowing slave traders to sell any Black person caught entering Maryland into slavery, regardless of their status. Frances could no longer return home. She moved in with family friends, William and Letitia George Still. William worked for the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society, but was known behind the scenes as the Father of the Underground Railroad.

Frances spoke at many anti-slavery meetings like these. (Library of Congress)

Frances was tired of facing discrimination everywhere she turned, both for being Black and for being a woman. She started using her gift with language to advocate for change, and wrote a speech she titled “The Elevation and Education of our People.” It was very powerful and soon Frances was being hired by various anti-slavery groups to present the speech in their communities. That fall, she traveled to 20 cities, speaking to audiences that were men and women, Black and white.

Frances also published her second volume of poetry, titled “Poems on Miscellaneous Subjects” that year. The book was a success. Buoyed by Frances’s growing popularity as a speaker, it sold 10,000 copies by 1857. She donated much of the profit to the Underground Railroad. In 1859, Frances’ short story “The Two Offers” became the first one ever published by a Black woman when it was featured in an issue of Anglo-African Magazine. She took a break from writing and touring after her 1860 wedding and the birth of her daughter. But when her husband died in 1864, she resumed lecturing and writing poetry for anti-slavery publications.

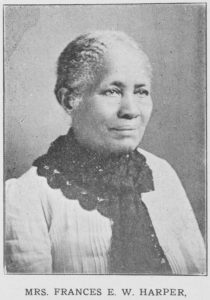

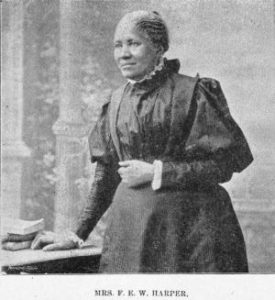

Frances (New York Public LIbrary).

After slavery was abolished, Frances shifted much of her energy into women’s suffrage. She attended the 1866 National Women’s Rights Convention, where a primary topic of discussion was the proposed 15th Amendment to the Constitution guaranteeing newly freed Black men the right to vote. Some women worried that this would delay or prevent the vote for women. Frances believed otherwise, and her speech titled “We Are All Bound Up Together” asked women to unite to fight for the vote for everyone. She was persuasive, and convention attendees met the next day to formally establish the American Equal Rights Association (“AERA”), with a stated goal of achieving the vote for Black men and all women.

This debate eventually divided the movement in 1869, when some white suffragettes left to form a rival organization that prioritized a constitutional amendment for women’s vote. The 15th Amendment was ratified in 1870, but suffragette movement didn’t come back together. Frances’ main takeaway from the turmoil was that as a Black women, she had a particularly challenging fight for equality and the vote. She couldn’t forgo either race or gender if she wanted her chance to fully participate as a citizen.

Frances spent the next 20 years speaking about women’s rights, racial equality, education, morality, and temperance. Her speeches often shared a common theme: her belief that if people could look beyond skin color and gender to discover their common interests as humans, American would have a happier and more stable society. She traveled around the country on lecture tours, and her fame and audiences grew. She spent her free time at home in Philadelphia writing poetry, short stories, and serialized novels. She inspired many women to form their own political advocacy clubs, which often were named in Frances’ honor.

Frances spent the next 20 years speaking about women’s rights, racial equality, education, morality, and temperance. Her speeches often shared a common theme: her belief that if people could look beyond skin color and gender to discover their common interests as humans, American would have a happier and more stable society. She traveled around the country on lecture tours, and her fame and audiences grew. She spent her free time at home in Philadelphia writing poetry, short stories, and serialized novels. She inspired many women to form their own political advocacy clubs, which often were named in Frances’ honor.

Brains, Heart & Courage

When Frances was born in 1825, Maryland was a free state. Her parents had free Black status, which meant that Frances was born free as well. Her parents died when Frances was only three. She went to live with her uncle, William Watkins, and his wife Henrietta who owned a school called the Watkins Academy for Negro Youth.

William and Henrietta believed that girls should have the same access to education as boys and enrolled Frances in the Academy. They also were very involved in the abolitionist cause and included Frances in discussions about the political issues of the day, encouraging her to think for herself.

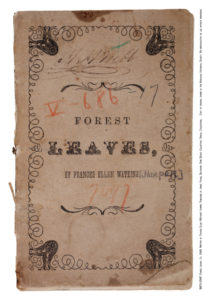

1849 edition of Frances’ first book of poetry (Maryland Historical Society).

The Academy curriculum ended at age 13, once the children were old enough to get a job and help support their families. Frances, an avid reader, found a job at a bookshop owned by a white family. Her duties involved shelving books, cleaning, and babysitting the family’s children. Her employers allowed her to stay at the bookstore and read once her tasks were done. She spent as much time there as she could, discovered poetry volumes on the shelves, and became captivated by it. Frances began experimenting with writing her own verse and found a new creative pastime. Six years later, in 1845, she published her first book of poems, titled Forest Leaves. It was an ode to her childhood love of nature.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- Frances was born in on September 24, 1825 in Baltimore, Maryland.

- On November 22, 1860, Frances married Fenton Harper, who had three children from a previous marriage. The couple had a daughter together named Mary. Fenton died in 1864.

- Frances’ published works include Forest Leaves (1845), Poems on Miscellaneous Subjects (1854), Moses: A Story of the Nile (1869), Achan’s Sin (1870), Sketches of Southern Life (1872), Light Beyond the Darkness (1890), Iola Leroy, or Shadows Uplifted (1892) and The Martyr of Alabama and Other Poems (1895).

- Frances was the director of the American Association of Education of Colored Youth.

- In 1874, Frances agreed to serve as a Superintendent for the “colored sections” of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU). Some white women objected to working across racial lines. While Frances was frustrated and amused by the hypocrisy of proclaiming Christian belief and being prejudiced, she believed it was worth trying to bridge the gap because working together for a common goal made its achievement more likely.

- At the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Frances presented the speech “Women’s Political Future.” Frances returned to her theme that women of all races should focus on their common values and work together.

- Frances was a founding member of the National Association of Colored Women (NACW), spoke at their first meeting in 1896, and was elected vice president the following year.

- Frances died in February 22, 1911 in Philadelphia, PA of heart disease

- Frances’ Unitarian faith was very important to her, and she made a point of reaching across religious lines to work together toward a more just society. In 1992, African American Unitarian Universalists installed a new headstone on her grave to commemorate the 100th anniversary of Iola Leroy.

Want to Know More?

Boyd, Dr. Melba Joyce. Discarded Legacy: Politics and Poetics in the Life of Frances E. W. Harper, 1825-1911 (African American Life Series 1994).

Alexander, Kerri Lee. “Frances Ellen Watkins Harper” (National Women’s History Museum, 2020).

Archives of Women’s Political Communications. “Frances Ellen Watkins Harper” (Iowa State University).

Encyclopedia.com Editors. “Iola Leroy” (Enyclopedia.com).

Logan, Shirley Wilson. “Frances E.W. Harper ‘Women’s Political Future’ (20 May 1893)” (Voices of Democracy 1 2006).

Mitchell, Koritha. “Know Frederick Douglass and Elizabeth Cady Stanton? You Should Also Know Frances E.W. Harper.” (Women’s Media Center Feb. 14, 2018).

Therkelsen, Sara A. & Maxfield-Parish, Chanomi. “Frances Ellen Watkins Harper” (Voices from the Gaps, 2004)