Inspiring Inventor

She was a teenage invalid who gained the strength to enroll in cooking school in the hopes of creating an independent life for herself. She ended up revolutionizing the field by inventing the modern recipe and authoring a cookbook that is still a staple in modern kitchens over 100 years later. Travel back to 1896 and meet Fannie Farmer…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

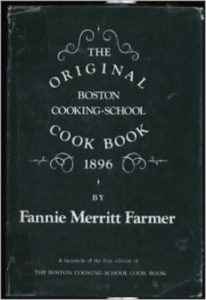

Fannie Farmer felt immense satisfaction as she looked down at the book she held in her hands. Its title: The Boston Cooking School Cookbook. Its author: Fannie Farmer. Its contents: 1850 recipes, all in a revolutionary new format. Each recipe had a list of carefully measured ingredients first, followed by step by step instructions explaining how to combine them to get a delicious final result.

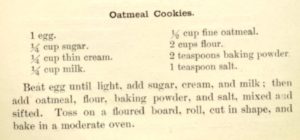

Before Fannie’s cookbook was published in 1896, most recipes called for people to measure ingredients by sight or with whatever they had around the kitchen. Even though standard measuring cups and spoons were available, most recipes didn’t reference them. Instead, they often called for a “handful” or “goodly amount” of something. The more precise recipes instructed people to use a mug, tea cup, or saucer for measuring dry ingredients and measure butter by using the size of an egg or a walnut.

Before Fannie’s cookbook was published in 1896, most recipes called for people to measure ingredients by sight or with whatever they had around the kitchen. Even though standard measuring cups and spoons were available, most recipes didn’t reference them. Instead, they often called for a “handful” or “goodly amount” of something. The more precise recipes instructed people to use a mug, tea cup, or saucer for measuring dry ingredients and measure butter by using the size of an egg or a walnut.

Food quality varied wildly depending on how the cook measured the ingredients. Using a big mug would add too much flour for a cake, leaving it dry and crumbly. Depending on the size of a saucer or teacup worth of sugar, cookies could be sickeningly sweet or taste like a cracker. The same cook could get different results from the same recipe if the “handful” they grabbed was smaller that day, or they grabbed a smaller mug. While experienced chefs could get away with cooking by sight and instinct, most people needed more guidance.

From her experience at the Boston Cooking School, Fannie knew that cooking was a science where standard measurements created better results. She wanted to write a cookbook that would save time wasted on recipes that don’t “turn out” and improve the quality of the finished product, so she started converting existing recipes into a new standard measurement format. This work was incredibly time consuming, as Fannie had to make each recipe several times to determine the ideal amount of ingredients, like whether a 1/3 or 1/2 cup of flour produced a better cake. With her cookbook, a baker would no longer have to ask the question “what went wrong – it was so good the last time I made it and I used the same recipe?”

From her experience at the Boston Cooking School, Fannie knew that cooking was a science where standard measurements created better results. She wanted to write a cookbook that would save time wasted on recipes that don’t “turn out” and improve the quality of the finished product, so she started converting existing recipes into a new standard measurement format. This work was incredibly time consuming, as Fannie had to make each recipe several times to determine the ideal amount of ingredients, like whether a 1/3 or 1/2 cup of flour produced a better cake. With her cookbook, a baker would no longer have to ask the question “what went wrong – it was so good the last time I made it and I used the same recipe?”

Fannie wanted her readers to feel like there was a cooking instructor right in their kitchen. She explained various cooking techniques. She provided detailed instructions about how to preserve and store fruits and vegetables by canning or drying them. The pages were full of tips about the importance of kitchen cleanliness and general housekeeping. Fannie was an early adopter of the importance of balanced nutrition to keep people healthy and strong and gave tips for planning meals.

Fannie wrote a dedication for her book that reads “It is my wish that it may not only be looked up on as a compilation of tried and tested recipes, but that it may awaken an interest through its condensed scientific knowledge which will lead to deeper thought and broader study of what to eat.” At the time, she didn’t know that she would become known as the “mother of level measurements.” Or that her cookbook, published when she was 39 years old, would be the smashing success that it was. Her publisher didn’t think it would sell, so he refused to pay the initial printing costs. Fannie paid for the first run of 3000 copies herself, and in return she kept the copyright and most of the profits.

Fannie wrote a dedication for her book that reads “It is my wish that it may not only be looked up on as a compilation of tried and tested recipes, but that it may awaken an interest through its condensed scientific knowledge which will lead to deeper thought and broader study of what to eat.” At the time, she didn’t know that she would become known as the “mother of level measurements.” Or that her cookbook, published when she was 39 years old, would be the smashing success that it was. Her publisher didn’t think it would sell, so he refused to pay the initial printing costs. Fannie paid for the first run of 3000 copies herself, and in return she kept the copyright and most of the profits.

The publisher should have had more faith, as Fannie’s cookbook sold 360,000 copies in her lifetime and made her a very wealthy woman. It is still in print today, selling more than 7 million copies since the day Fannie first held it in her hands.

The Power of the Wand

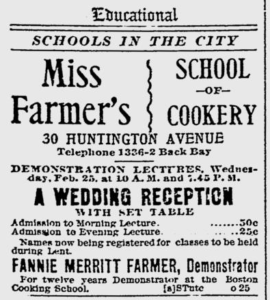

Fannie invented the modern recipe. She used her earnings from the Boston Cooking School Cookbook to start her own school, Miss Farmer’s School of Cookery. She bought the land, built the school and opened its doors on August 23, 1902. Her curriculum was practical, and her goal was to teach ordinary people how to cook delicious and nutritious meals for their families. She encouraged creativity and invention.

Fannie invented the modern recipe. She used her earnings from the Boston Cooking School Cookbook to start her own school, Miss Farmer’s School of Cookery. She bought the land, built the school and opened its doors on August 23, 1902. Her curriculum was practical, and her goal was to teach ordinary people how to cook delicious and nutritious meals for their families. She encouraged creativity and invention.

Following in Fannie’s footsteps is 15 year old Ariana Feygin from Excelsior, Minnesota. Ariana competed on Master Chef Junior with famous chef Gordon Ramsey when she was 12. She reads cookbooks like novels and creates her own recipes. She founded Ariana’s Kitchen, a private dinner catering company, with her dad, and donates the experience to raise money for local charities. Ariana posts regular videos teaching home chefs new recipes on Instagram.

Her Yellow Brick Road

As an unmarried woman, Fannie needed to find a way to support herself, and she had long been interested in food and diet. She enrolled in the Boston Cooking School, which had been founded by the Woman’s Education Association of Boston in 1879 after an economic recession. At the time, many men had lost their jobs or declared bankruptcy, and their wives had to learn a trade to support the family.

Students learned the skills needed to be a cook for a private home, a cook for an institution, or a cooking instructor. The School broke new ground by taking a scientific and professional approach to cooking and household management and assuring its students that anybody willing to study cooking could learn how to do it. The primary text used for study was a cookbook published in 1884 by Mary Johnson Lincoln, the first Boston Cooking School Principal. Mary left the school in 1885, two years before Fannie became a student.

Students learned the skills needed to be a cook for a private home, a cook for an institution, or a cooking instructor. The School broke new ground by taking a scientific and professional approach to cooking and household management and assuring its students that anybody willing to study cooking could learn how to do it. The primary text used for study was a cookbook published in 1884 by Mary Johnson Lincoln, the first Boston Cooking School Principal. Mary left the school in 1885, two years before Fannie became a student.

Fannie studied very hard, spent most of her time in the school’s kitchens, and rose to the top of her class. She loved learning the science behind the recipes and discovering how the end product differed depending on the amount of ingredients used. When she graduated in 1889, the School asked her to stay on as an instructor and administrator. Fannie agreed to join the staff as Assistant Principal.

One of Fannie’s favorite things to do was test and invent new recipes. She had trained her taste buds to recognize subtle layers of flavors and knew the science behind the “basic ingredients” like flour, baking powder, baking soda, corn starch, and salt. She wanted everyday chefs to be able to prepare the same meals people enjoyed in top restaurants.

If a restaurant chefs would not share their recipe, Fannie would order the dish for take out so she could experiment with it in her cooking school laboratory. She would evaluate the taste and texture, as make a hypothesis about which combination of ingredients were used, and test it. Depending on the outcome, she would adjust ingredients and test again. This process continued until the final product was the desired quality and taste.

If a restaurant chefs would not share their recipe, Fannie would order the dish for take out so she could experiment with it in her cooking school laboratory. She would evaluate the taste and texture, as make a hypothesis about which combination of ingredients were used, and test it. Depending on the outcome, she would adjust ingredients and test again. This process continued until the final product was the desired quality and taste.

Nutrition was not on most people’s radar, but Fannie knew from her experience as a teenage invalid that the right diet could help a sick person heal. The more she learned and experimented with recipes, the more convinced she became that there was a significant connection between diet and health. Fannie took a summer course at Harvard Medical School to learn more and ended up returning there later in her career as a lecturer about nutrition.

When the Director died in 1891, Fanny became Principal of the Boston Cooking School. She began work on her version of the Boston Cooking School Cookbook. She used some of Mary Lincoln’s recipes in the book and was initially accused of just republishing Mary’s work as her own. It wasn’t until people started using Fannie’s cookbook that they realized that her new format using level standard measurements was revolutionary.

When the Director died in 1891, Fanny became Principal of the Boston Cooking School. She began work on her version of the Boston Cooking School Cookbook. She used some of Mary Lincoln’s recipes in the book and was initially accused of just republishing Mary’s work as her own. It wasn’t until people started using Fannie’s cookbook that they realized that her new format using level standard measurements was revolutionary.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Fannie was raised in Medford, Massachusetts by parents who believed in education for girls as well as boys. Fannie had three younger sisters and they all loved to read like their mother did. Fannie’s dad was a printer and editor, so there were always books around.

Fannie lived a uneventful life until she had a stroke when she was 16 that left her partially paralyzed from her waist down. At the time, doctors required stroke patients to stay home in bed and do nothing. Reading and doing lessons was considered dangerous because it wasted energy that should be used for healing. Fannie had to drop out of high school, and her plans to go to college to become a teacher seemed impossible.

Fannie lived a uneventful life until she had a stroke when she was 16 that left her partially paralyzed from her waist down. At the time, doctors required stroke patients to stay home in bed and do nothing. Reading and doing lessons was considered dangerous because it wasted energy that should be used for healing. Fannie had to drop out of high school, and her plans to go to college to become a teacher seemed impossible.

Fannie’s recovery took months, and the only variety in her daily life was mealtime. Her mom brought her special meals designed to encourage her to eat as much as possible. If the meal didn’t look appealing and taste appetizing, Fannie often couldn’t muster up the energy to eat it. And if she didn’t eat, her body didn’t have the fuel it needed to heal, and she felt worse. Her mom would plate her sickroom meals on a tray with pretty china, and Fannie later recalled that she was more likely to eat a heart-shaped bread and butter sandwich instead of a slice of bread with a pat of butter.

The stroke changed the course of Fannie’s life. She walked with a permanent limp. Her family worried about her health and insisted that she live with them, which she did for several years instead of going to college. But Fannie longed for a more independent life and finally broke free in her 20s. Wealthy friends of her family, the Shaws, hired her to help with their children and the housework. Fannie enjoyed her work in the kitchen the most, and Mrs. Shaw encouraged her to pursue her interest for her future career.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- Fannie was born on March 23, 1857 in Boston, Massachusetts.

- Fannie gave weekly lectures about cooking and nutrition. She attracted crowds who enjoyed her charismatic public speaking. Her lectures were published in the Boston Evening Transcript. She started getting national press attention and accepted invitations to speak at womens’ clubs across the country.

- Fannie was one of the first women to give a lecture at Harvard Medical School. She instructed doctors about importance of healthy food for the sick. She taught them that “men and women are certainly but children of an older growth, which fact is especially emphasized during times of sickness and suffering.”

- Fannie published Food and Cookery for the Sick & Convalescent in 1904. Fannie wrote this book for trained nurses and caregivers, and believed it was more important than the cookbook. The book included recommendations for meals to help treat specific diseases, nutrition for food for children, and a proper diet to heal and avoid digestive issues. She dedicated it to her mother, who nursed her through her teenage stroke and recovery.

- Fannie also wrote Chafing Dish Possibilities (1898), What to Have for Dinner (1905), Catering for Special Occasions, with Menus and Recipes (1911), and A New Book of Cookery (1912).

- Fannie built a house for and supported her parents, sister, and other family members with the earnings from her cooking school, cookbook sales, and lectures.

- Fannie was the Food Editor for Women’s Home Companion magazine. She wrote a column for them with her sister for 10 years.

- Fannie suffered additional strokes when she was 50. The damage left her wheelchair bound but she kept working and public speaking. She gave a lecture from her 10 days before she died on January 15, 1915, from another stroke. She was 57. Alice Bradley, a teacher at Fannie’s school, led the school until it closed in 1944.

- Even though Fannie was a best-selling author and influential public speaker, the New York Times did not report on her death because it typically only used obituary space for men. They corrected this omission in 2018.

- Fannie’s cookbook was revised in 1979 and renamed The Fannie Farmer Cookbook. It has sold over 7 million copies worldwide.

- Fanny’s family licensed her name to the Archibald Candy Corporation after her death. They changed the spelling of her first name and created a brand of Fanny Farmer Candy Shops.

Want to Know More?

Eschner, Kat. Fannie Farmer Was The Original Rachel Ray (Smithsonian Magazine, Aug. 23, 2017).

History.com Editors. Fannie Farmer Opens Cooking School (November 24, 2009).

Mary Baker Eddy Library. “Chafing Dish Possibilities” by Fannie Merritt Farmer (Feb. 1, 2010)

Michigan State University. Feeding America (MSU Libraries Digital Depository Sept. 1, 2001 – Aug. 31, 2003).

Moskin, Julia “Overlooked No More: Fannie Farmer, Modern Cookery’s Pioneer” (New York Times, June 13, 2018)