Amazing Artist

She spent her childhood surrounded by the creativity and energy of the Harlem Renaissance but had to fight her way into art school because women weren’t supposed to aspire to be professional artists. She combined her classical training, family tradition of quilt making, and African cultural heritage to pave a unique trail through the art world. Travel back to her 1983 studio, admire her first story quilt, “Whose Afraid of Aunt Jemima?,” and meet Faith Ringgold...

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

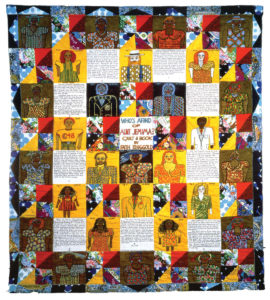

Faith stepped back to look at her finished quilt called Who’s Afraid of Aunt Jemima? It was 1983 and she just spent an entire year creating her first “story quilt.” It was a medium of art that she invented. And she knew that she finally found her artistic voice.

Who’s Afraid of Aunt Jemima?, Faith Ringgold, 1983

Who’s Afraid of Aunt Jemima? challenged society’s views of African American women. Through it, Faith told an alternate story of Aunt Jemima and portrayed her as a successful businesswoman. She counteracted the negative stereotype of the Black “mammy” who was happy merely being the caretaker of white children. Faith used portraits to show the various aspects of Jemima Blakely’s personality and career, as well as handwritten text that told her story.

Faith drew upon all her previous art work while designing and making Who’s Afraid of Aunt Jemima? The quilt itself was constructed as a checkerboard, a fairly traditional quilt design. Faith used acrylic paint to decorate 56 individual squares of fabric, then embroidered details and sewed the squares together. Finally, she assembled the fabric into a quilt and hand-sewed the entire thing.

Throughout the rest of her career, Faith made over 25 story quilts. She grouped her quilts into series that told a larger narrative. Each series was like a book, with each individual quilt as a chapter. In total, Faith made 5 series of story quilts — The French Collection; the American Collection; Woman on a Bridge; Home on Jones Road; and Soul Suite.

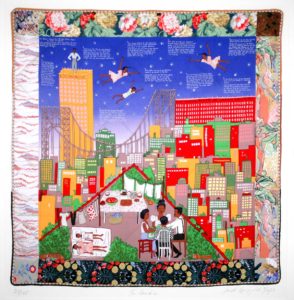

Tar Beach #2, Faith Ringgold, 1990

Faith drew inspiration from her own experiences for her quilt designs. In fact, many of her quilts were semi-biographical. She expressed her life, triumphs, and struggles through her quilts. And she blurred fact with fiction along the way.

For example, Tar Beach #2 told the story about summertime in Harlem when she was a child. It showed the tradition of African Americans gathering on the tar rooftops of their apartment buildings at the end of the day to enjoy the cool air. They had picnics, told stories, and gazed at the stars.

The quilt series, Coming to Jones Road, depicted Faith’s experiences when she and her husband moved to a new home in Englewood, New Jersey. The neighbors didn’t want a Black couple into their midst and hoped to push them out. In fact, they took Faith to court to block her plans to build a studio on their property. But Faith and her husband refused to back down. Instead, Faith used the experience as the inspiration for a quilt.

Faith advocated for social change through her art — she tackled topics such as civil rights, racial equity, gender equity, African American life and hardships. And she depicted strong African American women and other positive role models throughout her art.

Faith advocated for social change through her art — she tackled topics such as civil rights, racial equity, gender equity, African American life and hardships. And she depicted strong African American women and other positive role models throughout her art.

For many years, Faith sold very few works of art. Her work was too political. Her work was too controversial. Her work was discounted because she was a Black woman. And some of her work was considered to be folk art or crafts, rather than fine art. But Faith persevered. And her work eventually gained international recognition.

The Power of the Wand

Faith is an artist, author, and activist. She has been dedicated to racial and gender equity in the art world throughout her career. And she has encouraged Black girls to be strong and follow their dreams. Camryn Green is also dedicated to helping others through her artwork. She has been selling her art since she was 8 years old and donates all the proceeds to charitable organizations. For example, her donations help orphans in Liberia to receive an education.

Her Yellow Brick Road

Faith’s artistic style evolved over a number of years. She had studied the conventional art techniques in college, but quickly grew frustrated with its limitations. So she explored different painting styles. She eventually gave up her oil paints for the more modern acrylic paint and pop art style.

Faith was also intrigued by the three dimensional aspect of sculpture. But the traditional mediums of wood, metal, and clay weren’t an option for her — they aggravated her asthma. So she kept searching for other ways to express herself, and turned to her ancestral roots and family heritage for inspiration.

Nigerian Face Mask #1, Faith Ringgold, 1976

The women in Faith’s family had a long tradition of working with fabric — quilting, embroidery, sewing, and fashion design. In fact, her great-great grandmother was an enslaved woman who had sewed quilts for her master. And her techniques and knowledge were passed down from generation to generation.

Faith’s mother, Willi Jones, became her mentor. She introduced Faith to various fabric arts from different cultures — the designs of traditional Tibetan “thangkas,” the compositions of African quilts, and the colors and materials of African masks.

Before long, Faith began experimenting with different ways to work with fabric. She painted directly onto various types of fabric. She experimented with creating sculptures from fabric. She perfected a variety of sewing methods such as applique, embroidery, and quilting. And she explored the technique of photo-etching and printing onto fabric.

Echos of Harlem, Faith Ringgold, 1980

In addition, Faith was fascinated by the idea of storytelling through art. In particular, she was influenced by the manner in which African slaves kept their art and heritage alive through quilts. Slaves were banned from maintaining their African traditions, so they created art subversively through quilts (they were practical and necessary for warmth). Enslaved women decorated quilts with traditional African designs; told stories through quilts; and hid coded messages within quilts.

Faith combined all of these art mediums and traditional into her own style — quilts that were a fusion of crafts and modern art that told a story. And she embraced the idea of using traditional “women’s work” to challenge the place of women in the world.

Faith’s mom helped with her first quilt in 1980, called “Echos of Harlem.” Faith painted portraits of 30 different Harlem residents onto fabric, as well as a number of smaller panels of images and text. Then her mom helped her sew it all together into a quilt. It was the culmination of work by generations of women in her family.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Faith grew up surrounded by the people and energy of the Harlem Renaissance. Famous musicians such as Duke Ellington lived in her neighborhood. And her parents were both involved in the movement — her mother, Willi, was a seamstress and dress designer and her father, Andrew, was a creative storyteller.

Faith in 1993, faithringgold.com

Even though she was a child during the Great Depression, she didn’t feel the oppression. She just felt the love of her family. Her parents incorporated art into their daily lives and Faith was constantly surrounded by opportunities to be creative.

Faith struggled with severe asthma during her childhood. In fact, she was home from school during much of first and second grades due to her health. Faith spent that time with her mom, who gave her crayons and fabric scraps to keep her occupied.

Faith graduated from high school in 1948 and decided to pursue an art degree. So she applied to the City College of New York, which was just a few blocks from their apartment. Faith was shocked when they didn’t accept her, because it was the art college was for men only. It never occurred to her that she couldn’t be an artist.

Faith refused to take “no” for an answer and her determination paid off. Eventually, the administration offered to accept her into the college’s teaching institute (since it was acceptable for women to be teachers). She could study art so long as she also pursued a teaching certificate. But it wasn’t an easy road — some of her professors told her she would never become an artist. Faith graduated with a bachelor’s in art and teaching in 1955.

Faith refused to take “no” for an answer and her determination paid off. Eventually, the administration offered to accept her into the college’s teaching institute (since it was acceptable for women to be teachers). She could study art so long as she also pursued a teaching certificate. But it wasn’t an easy road — some of her professors told her she would never become an artist. Faith graduated with a bachelor’s in art and teaching in 1955.

After college, Faith taught art at the New York High School of Manual Training (now it’s John Jay High School). By then, she was a single mom of two daughters and worked on her masters’ degree at night. She received her master’s degree in 1959. Then, she quit teaching in 1973 to focus on her art.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- Faith Willi Jones was born in 1930 in New York City. She was the youngest of three children. Her parents moved to New York City from Florida as part of the Great Migration, in search of more opportunities for their children.

- Faith married jazz musician, Earl Wallace, in 1950. They had two daughters in 1952, Michele and Barbara. Then, she divorced Earl in 1956 because of his drug use. She went on to marry Burdette Ringgold in 1962.

- Faith wrote her autobiography in 1980, but couldn’t get it published for over 15 years. She also wrote over 15 illustrated children’s books. Her book, Tar Beach, won over 30 awards including the Caldecott Honor and the Coretta Scott King Award in 1991.

- Today, Faith’s quilts are in the permanent collections of the Guggenheim Museum, Museum of Modern Art, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. She has also designed mosaics for the subways systems in New York and Los Angeles.

- Faith has received a number of awards over the years:

- Smithsonian Craft Show 2017 Visionary Award

- National Endowment for the Arts Award

- Guggenheim Fellowship for painting

- NAACP Image Award

- Honorary doctorates from over 15 colleges

- Faith maintains studios in New Jersey and San Diego and is a professor emeritus at the University of California in San Diego.

- In 1999, Faith started Anyone Can Fly Foundation, a nonprofit organization that honors African American artists and shares their work with the general public. She also developed an app, Quiltuduko (which is like Sudoku with images) and has her own website (https://www.faithringgold.com).

Want to Know More?

Ringgold, Faith. We Flew Over the Bridge: The Memoirs of Faith Ringgold, Duke University Press, Durham: 2005.

Cameron, Dan. Dancing at the Louvre: Faith Ringgold’s French Collection and Other Story Quilts, University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles: 1998.

The Guggenheim Museums and Foundation, Faith Ringgold, October 5, 2018 (https://www.guggenheim.org/artwork/artist/faith-ringgold).

Witzling, R. Mara. Voicing Our Visions: Writings by Women Artists, Universe Publishing, New York: 1991.

Faith Ringgold (https://www.faithringgold.com)

Anyone Can Fly Foundation (https://www.anyonecanflyfoundation.org)