Culture Changer

Her sister’s disability inspired her to start a camp at her home for kids with special needs where they could play, have fun, and focus on what they can do, not what they can’t. The success of this camp, and its motto of “Everybody is Somebody,” provided the seed that grew into the Special Olympics. Travel back in time to the first Special Olympics in 1968 and meet Eunice Kennedy Shriver…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

Eunice Kennedy Shriver walked up to the podium at Soldier’s Field and welcomed athletes to the Chicago Special Olympics. It was July 20, 1968 — a warm and sunny day. In her speech, Eunice said:

“The Chicago Special Olympics prove a very fundamental fact, the fact that exceptional children — children with mental retardation — can be exceptional athletes. The fact that through sports they can realize their potential for growth.”

There was excitement in the air. About 1,000 participants and 100 spectators attended the Chicago Special Olympics — twice as many as they had anticipated. And athletes traveled from 26 states and Canada to participate in the event. For most competitors, it was the first time they stepped foot onto a real athletic field. And they had a blast!

Eunice overlooks Soldier Field at 1968 Games, courtesy of Special Olympics

Celebrity coaches donated their time, including Olympic gold medalist Jesse Owens. And hundreds of volunteers helped to coordinate the day. There were over 200 athletic events, including track and field, swimming, ice staking, baseball throw, and floor hockey.

Eunice worked with the Chicago Park District for over one year to plan the Chicago Special Olympics. Her contact was Anne Burke, who specialized in recreational activities for people with disabilities. Ann had submitted a proposal to the Kennedy’s family foundation (Joseph P. Kennedy Jr. (“JPK”) Foundation) — her idea was a track and field day for Chicago’s children with disabilities.

Anne’s proposal caught Eunice’s eye. She loved the idea, but immediately envisioned something much bigger. Eunice and Anne met to talk about the idea of a national competition modeled after the Olympics. The goal was to help people with disabilities experience the joy of competitive sports. And the JPK Foundation paid for most of the expenses associated with the event ($25,000 of the $28,000 budget).

Anne’s proposal caught Eunice’s eye. She loved the idea, but immediately envisioned something much bigger. Eunice and Anne met to talk about the idea of a national competition modeled after the Olympics. The goal was to help people with disabilities experience the joy of competitive sports. And the JPK Foundation paid for most of the expenses associated with the event ($25,000 of the $28,000 budget).

The Chicago Special Olympics was fabulously successful. In fact, Chicago’s mayor Richard Daly predicted that “the world will never be the same after this.” And he was right.

One month later, The Special Olympics, Inc. was formed as a nonprofit corporation. It quickly expanded across the country, creating new training programs for athletes and regional tryouts. Fifty years later, more than four million athletes from over 150 countries participate in the Special Olympic Games.

The Power of the Wand

Eunice devoted her entire life to advocating for people with disabilities. Before Eunice’s work, people with disabilities were isolated and forgotten — families were embarrassed; the public was prejudiced; and scientists thought that disabilities were the result of bad genes. Eunice helped to change the public’s view of intellectual disabilities forever. After she passed away, her family stated: “she set out to change the world and to change us, and she did that and more.”

Millions of individuals around the world have benefitted from Eunice’s tireless work. Today, most children with disabilities live with their families and receive community support to help them achieve their full potential. And girls with different abilities are able to follow their dreams and reach for the stars.

Girls like Chelsea Werner, Brittany Tagliareni, and JoJo Harris. Chelsea, who was born with Down’s Syndrome, is a two-time Special Olympic World Champion in gymnastics. Brittany, who was born with autism and some speech and fine motor challenges, won several gold medals in tennis at the 2018 Special Olympics USA Games in Seattle. Jojo, also born with autism, competed in the 2018 Games and is training for the 2022 USA Games in Orlando.

The Paralympic Games are part of Eunice’s inclusion legacy as well. Hannah Aspden was born without a left leg, because of a congenital disarticulation. But that never stopped her. She learned how to swim when she was four years old and began to compete a few years later. Hannah went on to become the youngest swimmer ever to join Team USA, at age 13. Then, she earned two bronze medals at the 2016 Summer Paralympics in Rio de Janiero. Watch for her at the 2021 Tokyo Paralympics!

Her Yellow Brick Road

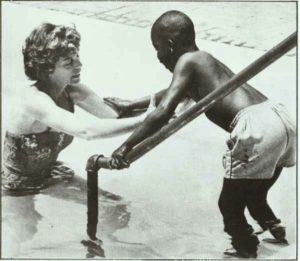

The idea of the Special Olympics began at Eunice’s farm in Maryland. It all started when the mother of a child with special needs shared her struggles with Eunice. She couldn’t find any summer activities for her daughter — mainstream camps wouldn’t take her and the government had no programs. So Eunice decided to do something about it.

Camp Shriver – the early years, courtesy of Special Olympics

Eunice invited local children with special needs to spend the summer at her farm — they called it Camp Shriver and the motto was “Everybody is Somebody.” She asked a family friend to help structure the activities (he was a PE teacher). Then, Eunice recruited high school and college students to be counselors. The Shriver children helped out as well. In total, there were 34 children and 26 counselors that first summer.

Through Camp Shriver, Eunice gave the children a place to play and have fun — they rode horses, participated in games, played tennis, and swam in the pool. The focus was on the kids abilities, rather than their disabilities. And they loved it!

Camp Shriver was a huge success. It operated for four summers and grew larger every year. Eunice used Camp Shriver as a laboratory — she kept track of the most successful activities. And her list became the basis for the 200 events at the Chicago Special Olympics.

Eunice was the driving force behind the Kennedy family tradition of advocacy for people with disabilities. She believed that people with disabilities could thrive independently if given the proper care, support and training. And that belief motivated her to keep pushing for change.

Eunice was involved in the JPK Foundation for most of her life. She was a founding trustee and served as its Executive Director for many years. Its charitable purpose was to fund research into the causes of intellectual disabilities, as well as treatments for the same. Eunice traveled around the country, visited institutions, and sought out experts in the field.

Eunice was involved in the JPK Foundation for most of her life. She was a founding trustee and served as its Executive Director for many years. Its charitable purpose was to fund research into the causes of intellectual disabilities, as well as treatments for the same. Eunice traveled around the country, visited institutions, and sought out experts in the field.

In addition, Eunice was a force to be reckoned with in DC for many years, especially during her brother’s presidency. She insisted that JFK address the needs of people with disabilities. She was so persistent that JFK reportedly said, “Let’s give Eunice whatever she wants so I can get on with the business of government.”

The result was what JFK called “a bold new approach” towards individuals with disabilities. Because of Eunice, his administration took the first steps in establishing new federal policy to support people with intellectual disabilities.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Eunice’s passion for helping people with disabilities started at a young age. Her older sister, Rosemary, was born with intellectual disabilities. Eunice developed a special bond with Rosemary while they were young — it was her job to include Rosemary in activities like sailing, swimming, and tennis. But Rosemary struggled to keep up.

The Kennedy Family, photograph by Richard Sears, John F Kennedy Presidential Library

Rosemary lived at home until she was about ten years old. She attended the local public school, repeating both kindergarten and first grade. Then, she was tutored at home for a year before being sent to boarding school. She went to five different boarding schools over the course of the next ten years.

The Kennedy family went through great lengths to keep Rosemary’s condition a secret. She was supervised closely in public, in an effort to hide her limitations and avoid any embarrassing situations. Back then, children with disabilities were usually hidden in overcrowded institutions, ignored and neglected.

Rosemary Kennedy, John F Kennedy Presidential Library

In 1941, Rosemary disappeared after a failed medical procedure left her completely disabled. She was 23 years old when she had a frontal lobe lobotomy, which was experimental at the time. She spent the rest of her life at an institution in Wisconsin. And Eunice’s parents refused to talk about it. For years, they insisted that Rosemary taught children with special needs at a Catholic school in the Midwest.

Eunice didn’t know what really happened to her sister for over ten years — and it was devastating for her. She was finally reunited with Rosemary after college.

Eunice assumed the oversight of Rosemary’s care after her father had a stroke in 1961. She monitored the services provided to Rosemary, consulted with experts, and ensured there were activities to fill Rosemary’s day. And she worked to integrate Rosemary back into the family’s life. Eunice was at Rosemary’s side when she passed away in 2005 at age 86.

Glinda’s Gallery

Check out Eunice’s digital scrapbook on Pinterest.

Just the Facts

- Eunice was born in Brookline, Massachusetts on July 10, 1921. She was the fifth child of nine Kennedy children.

- A few times during high school and college, Eunice considered becoming a nun. She was a devout Catholic and viewed social activism as an expression of her faith.

- Eunice graduated from Stanford University in 1943 with a degree in sociology.

- After college, Eunice worked at the US State Department, helping veterans readjust after World War II. She was also a social worker at a women’s penitentiary in West Virginia, then worked in Chicago’s juvenile court system.

- Eunice was diagnosed with Addison’s disease and struggled with health issues her entire life.

- Eunice married Sargent Shriver in 1953 (they had dated for 7 years). They had 5 children and 19 grandchildren, many of whom are involved in advocacy for individuals with disabilities.

- Eunice was involved with both the Special Olympics and the JPK Foundation until the day she died. In 1962, JFK established the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Now, its called the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development in her honor.

- Eunice died of a stroke on August 11, 2009 at age 88.

- Over her lifetime, Eunice received many awards and honors, including:

Presidential Medal of Freedom

Arthur Ashe Courage Award

Theodore Roosevelt Award of the NCAA

Women’s Hall of Fame inductee

Honored on The Extra Mile – Points of Light Volunteer Pathway

Want to Know More?

Larson, Kate Clifford. Rosemary: The Hidden Kennedy Daughter. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2015.

McNamara, Eileen. Eunice: The Kennedy Who Changed the World. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018.

Baranauckas, Carla. “Eunice Kennedy Shriver, Influential Founder of Special Olympics, Dies at 88.” New York Times (August 11, 2009) (https://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/12/us/12shriver.html).

Shriver, Eunice Kennedy. “Hope for Retarded Children.” Saturday Evening Post (September 22, 1962) (https://cpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/blogs.uoregon.edu/dist/d/16656/files/2018/11/Shriver-Hope-for-Retarded-Children-original-sozkov.pdf)

Eunice Kennedy Shriver: One Woman’s Vision