Amazing Artist

Her gift for poetry and her bravery in fighting against the anti-semitism that arose in response to Russian-Jewish immigrants in the 1880s combined to inspire Americans across the country to open their hearts to those seeking refuge from tyranny. Her words expanded the promise of the Statute of Liberty from a celebration of freedom to welcoming arms for all people around the world who share the American dream of liberty. Travel back to the first public reading of the 1883 poem “New Colossus” and meet Emma Lazarus…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

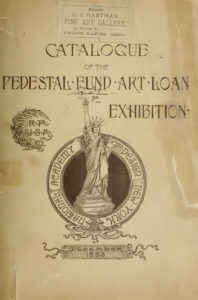

Emma Lazarus looked down at the catalogue for the fundraising event, Art Loan Fund Exhibition in Aid of the Bartholdi Pedestal Fund for the Statue of Liberty. And she was pleased to see that her poem, New Colossus, was printed in its entirety. She wrote the sonnet specifically for the Exhibition and hoped that it would bring in a respectable amount at the auction.

“New Colossus” was featured at the fundraiser for Statue of Liberty’s pedestal (Museum of the City of New York)

New Colossus was a highlight of the opening gala for the Exhibition. At 8 pm on the evening of December 3, 1883, about 1,500 people stood silent and listened as Emma’s sonnet was recited out loud. It was the only literary piece to be given such special treatment at the gala. Later in the evening, Emma’s handwritten manuscript of New Colossus was sold to the highest bidder for $1,500 — more than any other item at the auction (including work by Mark Twain and Walt Whitman).

The Exhibition was held in Brooklyn over the course of a month and all proceeds helped to pay for the pedestal for the new statue, Liberty Enlightening the World. It was a gift from the people of France to the people of America — the French raised all the money needed to build the statue itself. And the Americans were responsible for raising the money to built its pedestal. There was little interest in America, however, and the Statue of Liberty sat in a warehouse in Paris waiting for a home.

When she was first approached, Emma didn’t want to compose a sonnet for the Exhibition. She was an artist and didn’t do “work for hire.” But then her friend, Constance Cary Harrison, convinced her to reconsider. She suggested that Emma write a poem in honor of the Jewish refugees who had recently arrived in New York. They had been persecuted in Eastern Europe and sought safety in America.

Emma’s handwritten manuscript of “New Colossus” (Jewish Women’s Archive)

Once Emma found her inspiration, she wrote New Colossus in record time. And her sonnet gave the Statue of Liberty new meaning. Auguste Bartholdi had intended his work to inspire the ideal of liberty — a beacon shining out around the world. Instead, Emma called it the Mother of Exiles. She described the Statue of Liberty as welcoming the persecuted and downtrodden into America from around the world. People who sought liberty could find refuge here.

After the Exhibition, New Colossus was forgotten for many years. In the meantime, the Statue of Liberty had stood in New York’s Harbor since 1886. And Emma had died of Hodgkin’s lymphoma in 1887. But then, Georgina Schuyler ran across New Colossus in a used bookstore in Manhattan in 1901.

Georgina wanted to resurrect the sonnet in her friend’s honor. So she organized a group of Emma’s friends and civic leaders to lobby the government and raise funds to have New Colossus permanently associated with the Statue of Liberty. And her work paid off. Finally, a brass plaque with Emma’s sonnet was installed on the inner wall of the pedestal on May 3, 1903. And has been an integral part of the Statue of Liberty every since.

The Power of the Wand

Emma’s advocacy for Jewish immigrants inspired her to wrote one of the most famous poems in American history. New Colossus has defined the Statue of Liberty and represented the promise of a new life in America. And her words have given hope to generations of immigrants ever since. Every since our country has been founded, immigrants have arrived to follow the American Dream. THEDREAM.US provides scholarships for teen immigrants to attend college and follow their dreams.

Her Yellow Brick Road

Emma’s family was never strictly observant of Jewish traditions. But an event occurred in June, 1877 that made a lasting impression on her. The successful banker, Joseph Seligman, was refused a room at the Grand Union Hotel in Saratoga because he was Jewish. Henry Hilton had recently purchased the Grand Union Hotel and instituted the anti-Semitic policy. The New York Jewish community was outraged. And Emma became passionate about her Jewish heritage.

Then, Tsar Alexander II was killed by a bomb in St. Petersburg in 1881, which set off a wave of anti-Jewish violence throughout Russia. The Jewish community was blamed for the Tsar’s assassination. Mobs took matters into their own hands and the government refused to get involved. There were pogroms in over 150 Russian and Ukrainian towns.

Then, Tsar Alexander II was killed by a bomb in St. Petersburg in 1881, which set off a wave of anti-Jewish violence throughout Russia. The Jewish community was blamed for the Tsar’s assassination. Mobs took matters into their own hands and the government refused to get involved. There were pogroms in over 150 Russian and Ukrainian towns.

Easter European Jews fled to America. Month after month, over 2,000 people arrived at Castle Garden in New York (the processing facility for immigrants before Ellis Island was built). They were penniless, desperate, and homeless. Before long, Castle Garden was over capacity and New York City officials had to figure out what to do with the flood of immigrants. So they opened an old hospital building on Ward Island to house them all.

Emma was horrified by the persecution of Russian Jews and became a tireless advocate on their behalf. She visited Ward’s Island and exposed their desperate living conditions. She volunteered for the Hebrew Emigrant Aid Society and taught English. She donated money. She set up job training and education for the refugees. She raised money, at both home and in Europe. She criticized American Jews for not doing enough to support the refugees. And she was instrumental in the founding of the Hebrew Technical Institute of New York.

Over time, however, Emma became discouraged by the anti-Semitism she encountered during her advocacy of the refugees. And it made a big impact on her views. She began to think that the only way European Jews would be safe was in their own homeland. She advocated for the creation of an independent Jewish state in Palestine. And she was ridiculed for the idea. Emma was ahead of her time — Zionism wouldn’t become a movement for another 20 years.

Over time, however, Emma became discouraged by the anti-Semitism she encountered during her advocacy of the refugees. And it made a big impact on her views. She began to think that the only way European Jews would be safe was in their own homeland. She advocated for the creation of an independent Jewish state in Palestine. And she was ridiculed for the idea. Emma was ahead of her time — Zionism wouldn’t become a movement for another 20 years.

Emma’s experience with the Russian Jews greatly influenced her writing, which was regularly published in the American Hebrew magazine. She composed poems denouncing anti-Semitism. She wrote a five-act play, The Dance to the Death, that dealt with the atrocities that German Jews faced in the 14th Century. She wrote about the persecution and expulsion of Jews from Spain in 1492. She wrote essays about the pogroms of Eastern Europe. And she composed a poem in honor of the refugees,New Colossus.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Emma grew up in a life of privilege as part of a wealthy Sephardic Jewish family. She was considered to be part of the American Jewish nobility — her ancestors were some of the first Jews to immigrate to America. They arrived from Brazil when New York City was part of the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam.

Emma and her sisters were educated at home by tutors. She studied German, French, Italian, music, art, literature and history. And she devoured books. Emma used her father’s library as a classroom and read everything from Greek mythology to Shakespeare to Edgar Allen Poe.

Before long, Emma began to write poems. In fact, she wrote so many poems as a teenager that her father paid to have them published. Poems and Translations: Written Between the Ages of Fourteen and Sixteen was printed when she was 17 years old.

Before long, Emma began to write poems. In fact, she wrote so many poems as a teenager that her father paid to have them published. Poems and Translations: Written Between the Ages of Fourteen and Sixteen was printed when she was 17 years old.

Emma sent a copy of her first book to Ralph Waldo Emerson, one of the most influential writers at the time. Before long, Emerson became Emma’s mentor. They exchanged many letters over the years and she dedicated a poem in her second book to him.

Over time, Emma went on to publish short stories, plays, essays and novels. Emma also used her language skills to translate the work of various poets from German to English. She was especially drawn to the work of Jewish poets from history. For example, she translated the most of the work by Heinrich Heine, a German Jewish poet. She also translated the medieval Hebrew poetry, focusing on Spanish poets whose work had been translated to German. Emma’s translation work grew in importance as she became more passionate about Jewish culture and history.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- Emma was born on July 22, 1849 in New York City. She had 5 sisters and one brother. They lived in a brownstone in the heart of the City, near Union Square.

- Emma’s father made his wealth in the sugar business. His business partner owned a plantation in Louisiana. They brought the sugar cane to a distillery and refinery in New York.

- Emma never married and lived in her parents house her entire life.

- Emma immersed herself in the culture and society of New York City during the Gilded Age and was friends with members of the intellectual elite.

- Emma traveled to Europe twice. In 1883, she traveled to London and Paris to meet with Jewish philanthropists to raise funds for the Russian Jews, as well as promote her idea of a jewish state. Then, she traveled throughout Europe for two years (1995-1887).

- Emma died in New York City on November 19, 1887 at age 38, most likely from Hodgkin’s lymphoma. She is buried in Queens.

- In 1941, the Emma Lazarus Federation was founded to further her legacy. It was a women’s organization that advocated for civil rights and women’s rights. Members were called “The Emmas.”

- Every year, the American Jewish Heritage Foundation presents the Emma Lazarus Statue of Liberty Award to “an individual or group whose contribution reflects the highest values of the American Jewish community.”

Want to Know More?

Hollander, John, ed. Emma Lazarus: Selected Poems. The Library of America, 2005.

Schor, Esther. Emma Lazarus. New York: Schocken Books, 2006.

Young, Bette Roth. Emma Lazarus in her World: Life and Letters. Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society, 1995.

Johnson, Susan. “The New Colossus.” Museum of the City of New York, February 16, 2017 (https://www.mcny.org/story/new-colossus).

Women of Valor: Emma Lazarus. Jewish Women Archives (https://jwa.org/womenofvalor/lazarus).