Culture Changer

She grew up listening to her grandmother tell the stories of life as an enslaved women, including her acts of rebellion against injustice. The lessons from her childhood stayed with her and inspired her to fight for the dignity of every person. Before long, she became an integral part of the Civil Rights Movement. March back to 1960 and meet Ella Baker…

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

The Power of the Wand

Her Yellow Brick Road

Brains, Heart & Courage

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

Her Ruby Shoe Moment

Ella Baker felt a jolt of excitement as she looked out at the full auditorium at Shaw University. It was April, 1960, and she organized a group of college students to meet and discuss their role in the Civil Rights Movement. Ella was overwhelmed with the enthusiasm — over 200 students attended from over 19 colleges.

Ella was inspired by the college students who sat down at the whites-only lunch counter at Woolworth’s in Greensboro, North Carolina on February 1, 1960. The four men refused to leave until closing, then returned with more college students the next day. It was the first sit-in of the Civil Rights Movement, and the idea spread like wildfire.

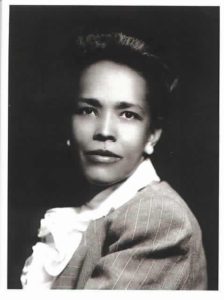

Ella Baker (Ella Baker Center for Human Rights)

It was the grass roots movement that Ella had been waiting for. And she was thrilled. Ella had devoted her entire career to the rights of African Americans. She wanted every person’s voice to be heard and was passionate about empowering the ordinary person to develop their strength, advocate for themselves and their own beliefs.

As Ella created the agenda for the 1960 conference, she emphasized that the meeting should be student-driven, with adults merely as a resource. She believed that students needed independence to develop their ideas and grow into community leaders. She felt strongly that the students shouldn’t be subject to the agenda of the adults leading the current organizations. They had a unique perspective with new ideas to offer.

This put her at odds with Martin Luther King, Jr, however. He suggested that the students become the “youth” arm of his organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), which would oversee and organize their activities. So Ella walked out of the conference.

But before leaving, Ella encouraged the students to start their own organization. And they did. They established the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), agreed on a statement of purpose, and made plans to meet again.

But before leaving, Ella encouraged the students to start their own organization. And they did. They established the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), agreed on a statement of purpose, and made plans to meet again.

Ella worked tirelessly to get the SNCC off the ground. She leased office space, hired an administrator, and served as its fundraiser. She also convinced the SCLC to support it financially. Before long, the SNCC was a formal organization with delegates from each state, an executive committee, staff, and a newsletter.

Ella provided unwavering support to the students. She was present at every meeting, acting as a resource and providing advice if requested. She listened closely and taught them that everyone had something to give. She also emphasized the power of grass-roots movements and local leadership.

Before long, the SNCC became a powerful advocate for human rights in America. It was involved in most of the nonviolent activities of the Civil Rights Movement — sit-ins; Freedom Rides; Mississippi Summer; boycotts; protests; and voter registration drives. And Ella was there every step of the way.

The Power of the Wand

Ella provided behind-the-scenes support to many of the organizations that were involved in the Civil Rights Movement. And she continued to be a respected leader in the fight for human rights until her death. In fact, she earned the nickname, “Fundi,” which is a Swahili word that refers to the person in the community who passes on the wisdom of elders to the next generation.

Today, the Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Change provides various learning opportunities for young people to learn about nonviolence advocacy and grassroots leadership.

Her Yellow Brick Road

Ella moved to New York City after her college graduation in 1927. And it was an eye opening experience. She soaked up the excitement of the Harlem Renaissance and was exposed to new ideas. She took advantage of all that New York had to offer, including sociology classes at Columbia University.

Ella Baker (North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources)

Ella grew passionate about the social and economic conditions of African Americans. Before long, she got involved with a variety of community organizations. She thrived when she was very busy with many different organizations and causes at once — education, library services, journalism, and women’s rights were just a few. However, she eventually focused her efforts on organizing and empowering people at the grassroots level.

In 1930, Ella became a founding member of the Young Negroes Cooperative League. The purpose of the organization was to help African Americans gain economic power through collective planning and purchasing. She was its first secretary and became its national director in 1931. Membership was limited to African Americans between ages 18-35. Within one year, it had over 400 members. Ella traveled throughout the country, speaking to local councils and helping them to solve problems. One of her goals was to establish “buying clubs” for African Americans.

By 1940, Ella was involved with the National Advancement for Colored People (NAACP). At first, she was an advisor to its New York Youth Council. Then, Ella took a full time job in 1941 as Assistant Field Secretary at the NAACP. Within a few years, she was promoted to the Director of Branches. While in these roles, Ella developed leadership training for members of the various NAACP chapters and branches, as well as training sessions for staff. She traveled all over the country, sometimes on the road for over 6 months each year. The more she spoke with local chapters, the more passionate she became about empowering them. She wanted local chapters to exercise independence in both their operations and advocacy efforts. She also wanted to involve the local chapters in national policy decisions. Ella resigned from the NAACP in 1946, in part because she disagreed with its top-down structure.

By 1940, Ella was involved with the National Advancement for Colored People (NAACP). At first, she was an advisor to its New York Youth Council. Then, Ella took a full time job in 1941 as Assistant Field Secretary at the NAACP. Within a few years, she was promoted to the Director of Branches. While in these roles, Ella developed leadership training for members of the various NAACP chapters and branches, as well as training sessions for staff. She traveled all over the country, sometimes on the road for over 6 months each year. The more she spoke with local chapters, the more passionate she became about empowering them. She wanted local chapters to exercise independence in both their operations and advocacy efforts. She also wanted to involve the local chapters in national policy decisions. Ella resigned from the NAACP in 1946, in part because she disagreed with its top-down structure.

Ella was energized by the Civil Rights Movement and became involved in many different organizations that were devoted to furthering the cause. For example, Ella was also involved in the Montgomery bus boycott and considered Rosa Parks a close friend. In addition, she was dedicated to the school desegregation movement and co-founded the organization, In Friendship, which advocated for integrated schools in the South.

In 1958, Ella moved to Atlanta to help found Martin Luther King Jr’s new organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). She served as one of its first Executive Directors and worked with MLK to shape the SCLC from an informal group of ministers to a powerful national organization. Within 6 months, Ella created and oversaw the Crusade for Citizenship campaign, which organized voter registration drives throughout the South.

Then Ella heard about 4 Black college students who sat at a whites-only lunch counter at Woolworth’s and refused to move. She was thrilled with the grassroots action and knew she had to get involved.

Brains, Heart & Courage

Ella Baker came from a long line of strong women. Her family taught by example that every person has inherent dignity, and it was a lesson that stayed with her. Ella’s grandmother had been enslaved, and she listened to her tell stories about slave revolts and plantation life.. Her grandmother was punished for refusing to marry a man chosen for her by her “owner.” She was demoted from housemaid to field worker, but it was worth it because she could marry the man she loved. Ella’s grandmother was her hero, because she stood up for herself despite the consequences.

Ella Baker (North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources)

After the Civil War, Ella’s grandparents had the opportunity to buy land that was formerly part of the plantation on which they were enslaved. They bought the land with other relatives, then subdivided it among family. The lived on and worked the land, which was a great source of pride for the family. When Ella was 7 years old, she moved to her grandparent’s farm. After that, she grew up surrounded by extended family, with a sense of community that shared the fruits of its labor.

Ella’s family was involved in the local Baptist church during her childhood. In fact, Ella developed her public speaking abilities while leading the various children’s groups at church. Then, she went on to participate in various speech contests.

Ella’s mother wasn’t very impressed with the schools near their home. So, Ella enrolled at Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina starting in high school. She was a boarding student and had to work on campus to earn her tuition – Ella was both a waitress and worked in the chemistry lab. She joined the debate team, and her skill helped the team win competitions. Ella graduated from high school as valedictorian of her class, then continued on at Shaw for college.

Shaw University was a strict Baptist college that had a lot of rules. Ella followed most of the rules but challenged those policies that she felt were unjust, especially the special rules for women. For example, she objected to the rule that men and women couldn’t walk on campus together. She also protested against the dress code, which prohibited women from wearing silk stockings. The president of the university felt that Ella was a trouble-maker and tried to have her expelled when she was a senior in college. But the faculty stood up for her, and she was allowed to graduate with a bachelor’s degree in 1927.

Glinda’s Gallery

Just the Facts

- Ella was born in Norfolk, Virginia, on December 13, 1903.

- Ella moved to North Carolina when she was 7 years old.

- Ella attended Shaw University for high school and college. She graduated from college in 1927.

- Ella married TJ Robinson in 1940. Together, they raised her niece, Jackie.

- Ella worked with countless social activism organizations throughout her adult life, from the time she graduated from college until the day she died.

- Baker died on her 83rd birthday, on December 13, 1986, in New York City.

- In 1981, Ella’s life was portrayed in a documentary film called “Fundi: The Story of Ella Baker.”

- Ella’s legacy lives on through the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights, which aims to combat the problems of mass incarceration and strengthen communities for minorities and low-income people.

Want to Know More?

Ella Baker Center for Humans Rights (https://ellabakercenter.org/who-was-ella-baker/).

“Baker, Ella Josephine.” The Martin Luther King Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University (https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/encyclopedia/baker-ella-josephine).

“Ella Baker.” Digital SNC Gateway (https://snccdigital.org/people/ella-baker/).

Ransby, Barbara. Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement: a radical democratic vision. Raleigh: UNC Press, 2005.

Grant, Joanne. Ella Baker: Freedom Bound. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1998.